Beyond Recognition: What Machines Don't Read

September 14, 2016

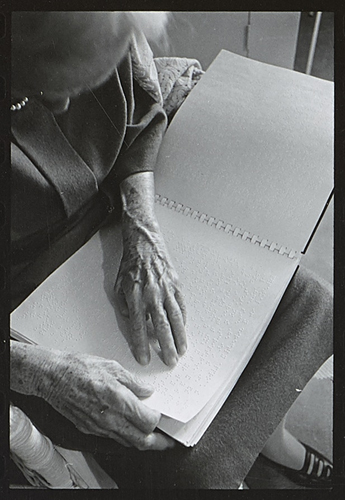

Helen Keller reading braille at her home in Westport, Connecticut. October 1965.

I am delighted that the fifth in our series of posts focusing on the Helen Keller Digitization Project is from Mara Mills New York University Associate Professor of Media, Culture and Communication. Mara’s post - on the continued importance of human transcribers - is fascinating and I encourage everyone to read it. Many thanks, Mara!

On Helen Keller’s birthday this year, archivist Helen Selsdon wrote a piece for the AFB blog about the work of three volunteers who have transcribed, text corrected, or described well over 6,000 items from the Helen Keller Archival Collection. Keller’s manuscripts are currently being digitized thanks to a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. But why do we still need human transcribers? Can’t machines read? Why not just use Optical Character Recognition (OCR)?

After a scanner turns a document into a page image, OCR software recognizes letter shapes to generate a corresponding text file. This text file is then searchable, amenable to database queries, and compatible with the text-to-speech (TTS) software used by many blind readers. But the machine recognition process is often inaccurate. Certain kinds of documents, including most historical manuscripts, trip up OCR. Examples include:

- Faint, blurry, smeared, wrinkled, or otherwise damaged documents

- Very small or very large text

- Handwritten documents

- Languages that include "special characters"

- Mathematical or map symbols and other graphic elements

- Nonlinear or misaligned text

- Text on curved surfaces, such as cans and pill bottles (a particular concern for blind readers using handheld TTS devices)

Harvey Lauer, a former technology transfer specialist at the Hines VA Hospital, commented on the glitches of text-to-speech for blind readers like himself in 1994: "When you use a current OCR machine to scan a page with a complex format, the data is frequently rearranged to the point where it’s unusable. Such items as titles, captions and dollar amounts are frequently scrambled together. It makes me feel as if I am eating food that someone else has first chewed." Twenty years later, complex formatting continues to pose problems for TTS—a particular historical irony when one considers that OCR was originally developed to provide blind readers access to print.

Nor does OCR software work for all languages. ABBYY FineReader, for instance, encompasses 190 languages, but only provides dictionary support for 48. Moreover the speed and accuracy of recognition tends to be slower for Asian languages. Historian of computing Dongoh Park roots these inequalities in information technologies that were initially designed by or for English speakers, resulting in a durable script imperialism. "The English language has long served as the lingua franca of computing and computer mediated communication. Many of the core applications and standards of digital computing, including programming languages, operating systems, and applications, have been developed, documented, and serviced in English." Historical languages and manuscripts are similarly refractory to machine reading. Hannah Alpert-Abrams, a scholar who works with Mexican colonial documents, explains that OCR routinely fails with pages that contain multiple languages and obsolete or non-standard spelling or characters.

Less widely known is the fact that braille documents also thwart machine reading. Optical braille recognition technology is still very much a work in progress, made difficult by the lack of contrast on most braille pages. In the online Helen Keller Archival Collection, a braille letter from 1948 yields the following misrecognized text:

f '¦ ¦" "'.¦ '¦' si' ¦. : ' ¦ 'v'..:.; ¦ i ..¦ ' ¦ ; ". : N II

W9|

V.-nt:

wM

Most other items written in braille produce no output at all.

Human transcribers are thus essential for correcting OCR output ("machine-assisted transcription"), describing charts and images, and transcribing documents in formats like braille that cannot be read by machine at all. You, dear reader, are invited to volunteer as a transcriber with the Helen Keller Digitization Project, simply by making use of the text-correction interface that is built right into the site. These text files allow blind readers to access the collection, and they enable everyone to search the content online.

If you wish to volunteer as a transcriber, please email Helen Selsdon at hselsdon@afb.net. Thank you.