"I know that, on any job in almost every situation, I am just never going to have the same amount of raw speed as a sighted peer, but I make up for that with much higher quality work output. I catch misspellings using JAWS and/or the Optacon [a tool that uses a small camera to transmit an image of print to pins that raise and lower and are read with a fingertip]. With the Optacon, I once caught a misspelling seven sighted people missed, and they were astounded because they were all trained in proofreading, and I was not. I also catch duplicate entries in our software program much faster than others, as I pay close attention to detail." —White male in his 40s who is congenitally visually impaired

The bottom line for employers is that they want productive workers who can get the job done. For some participants, "simple" tasks present challenges. Participants were asked about three common tasks that may present unique challenges to employees who are blind, have low vision, or are deafblind: organizing/submitting receipts, completing expense reports, and completing CAPTCHAs, automated tests to tell humans and computers apart. Additionally, changes in one’s visual abilities often necessitates needing to learn new ways of doing things and using new technology tools to maintain productivity and retain one’s employment.

Receipts and Expense Reports

Many employees must organize/submit receipts and/or complete expense reports. Of 310 participants, just over half (n=163, 52.6%) reported that they had to organize, submit, and complete receipts and/or expense reports. The 163 participants were provided a list of statements that described their experience with these tasks with multiple responses permitted. Their responses included that they:

- Requested receipts be sent electronically (n=104)

- Used a person to assist with viewing and organizing receipts (n=83)

- Independently completed the process to submit an expense report (n=67)

- Used an app or OCR to view and organize receipts (n=58)

- Required assistance to complete the process to submit an expense report (n=58)

- Used a visual interpreting service when viewing and organizing receipts (n=36)

- Had someone else complete the process to submit an expense report because the process was not accessible (n=29)

- Were able to see and organize receipts (n=26)

CAPTCHAs

To maintain security, some websites use CAPTCHAs which often require interacting with visual elements. The researchers wanted to understand the CAPTCHA experiences of people who are blind or have low vision. When provided a list of CAPTCHA types, participants could select all those that were not accessible to them. The 237 participants selected CAPTCHAs that included:

- Identifying pictures in a group (n=213)

- Reading and typing a combination of letters and numbers (n=199)

- Checking a box such as "I am not a robot." (n=72)

- Completing a math problem (n=40)

The most common complaint participants had with CAPTCHAs was the poor audio quality of audible CAPTCHA alternatives, which participants often found difficult to understand and accurately decode. Some participants with low vision also reported that visual CAPTCHAs were difficult to decipher since the picture was often deliberately distorted or scrambled.

Participants were asked to select their level of agreement with the statement: Typically, I find that the alternative CAPTCHAs are accessible to me. Of the 224 participants who responded, 119 (53.2%) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement; however, 66 (29.5%) disagreed or strongly disagreed, indicating that CAPTCHAs encountered by study participants are a significant accessibility problem.

"I had recently been employed when I lost my vision, and the company thankfully kept me on. I was steadfast in my communication during [training from] VR with them; sending bi-weekly updates on my training and updating them constantly on what I was learning and my return-to-work date. I also had two hard conversations with my current boss about projects I was working on that just didn’t feel like the most efficient job for me anymore. I feel being honest and leading with what I could bring to the table was good for my successful return." —White male in his 70s

Changes in Visual Abilities

Though 65% of the participants had acquired their visual impairment before 2 years of age, the others acquired their visual impairment at a later time — 18% before 19 years of age and the remaining 17% as adults. Regardless of when one becomes visually impaired, there are many eye conditions that result in a decrease in visual ability over time, for example, retinitis pigmentosa. In the survey, participants were asked if their ability to read print had decreased in the last 5 years with 57 (55.9%) of 102 participants reporting this was the case. They reported that the tools they had begun to use to access print included screen magnification software (n=37), screen reader software (n=36), large print (n=26), and/or braille (n=10) because of the decrease in their ability to read print. Of 99 participants, 31 (31.3%) expected their visual abilities would change in the next 5 years, 17 (17.2%) were unsure if there would be a change, and 51 (51.5%) reported they did not expect a change.

The 57 participants who reported a decrease in their ability to read print in the last 5 years were asked if they made accommodation requests of their employer as their visual ability decreased. Thirty-two (56.1%) participants asked for accommodations. In an open-ended survey question, the 57 participants were asked to discuss the process they underwent for requesting accommodations and the outcome of the request. Participants requested a variety of accommodations including new hardware or software (braille display, CCTV, screen reader); changes to workstation setup to improve lighting; receiving printed materials by email; sighted assistance; or additional technology training. For many participants, the accommodation process was straightforward, and requests were granted. However, a few participants reported that some or all the accommodations they requested were denied or delayed, resulting in frustration or reduced productivity.

The 57 participants were also asked about what technology accommodations they considered incorporating into their workday. Most participants reported that they did incorporate new technology or increase their use of AT that they had already begun using before their recent decrease in vision. Specific technologies included CCTVs/video magnifiers, screen magnification software as well as screen reader software and braille displays. A few participants stated that they did not have the time or resources to learn new technology.

Finally, the 57 participants were asked about what technology and accommodations they believe they would need going forward if they were to lose more usable vision. A mix of responses were offered for this question, including some participants mentioning fears of having to retire, quit, or even of being fired if they lost more vision. The most frequently mentioned specific technology and accommodations that would be needed if more vision was lost included JAWS (screen reader software), ZoomText (screen magnification software), and braille.

"My biggest issue is multiple windows open at one time. With Windows 10, Microsoft has made it much harder to [visually] distinguish the title bars of open/active applications/windows from others. Windows 7 was much easier in this regard. I find it very frustrating with many windows open finding the ‘right’ close box, and I am frequently closing the wrong window application. With Microsoft Office products and some other applications, they seem to rely more and more on icons and ‘ribbons.’ I find icons hard to determine what they mean. I prefer words and labels. I would rather options be within menus to find them, rather than icons on a ‘ribbon.’" —White male in his 50s who is congenitally visually impaired

Efficiency

In any workplace there are certain employees who are more efficient at one task than other employees. Participants were asked to describe the types of technology-related tasks they believed they did less efficiently than sighted colleagues.

Participants agreed that accessibility limitations directly impacted their efficiency and productivity at work. They reported needing more time than sighted colleagues to complete tasks, such as working on spreadsheets or skimming large documents. While some challenges may be inherent to visual impairment (e.g., difficulty simultaneously listening to a screen reader and a client on the phone; difficulty seeing a document all at once with screen enlargement software), other challenges may be mitigated with improved accessibility of mainstream technologies. Training is important as well; for example, if an individual learns to use shortcut keys, they can quickly and efficiently move between windows and close them.

Similarly, the participants were asked to share about the types of technology-related tasks they believed they did more efficiently than sighted colleagues. Participants stated that although they may need more time than their colleagues to complete a task, they could complete the task more accurately or precisely. For example, 49 participants said they read faster in general, 66 reported they were more detailed proofreaders, and 13 participants described reading documents in more depth than sighted colleagues because they needed to listen to the entire document rather than skim it. This enabled them to catch spelling and grammatical errors that others may miss, or to gain a deeper understanding of the material. Some participants also stated that the need to memorize information improved the quality of their work.

"I do think there is more effort and intentionality required for my work to get accomplished compared to a nondisabled peer. However, I make this effort a part of my work ethic that compliments the services I offer. My lifestyle does not lend [itself] to poor planning and poor communication. My clients get both a committed individual that accomplishes the various tasks assigned, but as well thinks forward on what is necessary to be a part of the team. If I do not do this, I end up being left out, so much of my value proposition to my clients is that I can work independently without oversight while striving to be a team player." —White male in his 30s who became visually impaired in childhood

When asked about technology they would like to see developed that would increase their productivity, participants responded that they would like companies to create content and technology that is accessible from the onset. They would like to see the enforcement of laws related to accessibility and improvements to products, such as better OCR software, more enhanced voice controls, and affordable multiline braille displays.

Telework and the COVID-19 Pandemic

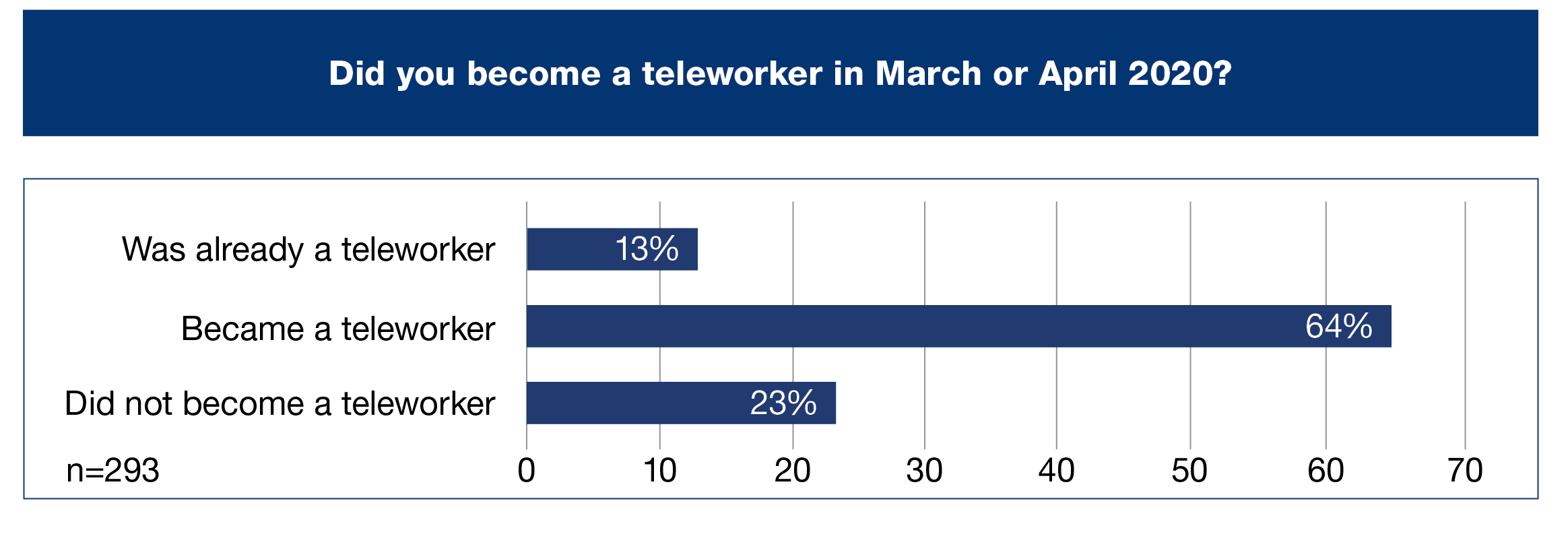

Teleworking was part of the U.S. employment structure prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. There were 125 (41.4%) of 327 participants who reported they were part-time or full-time teleworkers prior to March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. There were 293 of 327 (89.6%) participants who reported that they teleworked in either March or April 2020. Figure 7 shows the effect of the pandemic on telework.

Figure 7. Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Telework

"I think [the] COVID-19 [pandemic] has demonstrated that we are rethinking he conventional workplace model. Working from home is an attractive choice for all, not just the disabled community. Technology is overcoming the sense of disconnectedness typically associated with working from home." —White male in his 40s who became visually impaired in childhood

Teleworkers were asked to select the statement that best described their experience since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the 224 participants who responded, 165 (73.7%) had worked consistently as a teleworker, 29 (12.9%) worked some of the time as a teleworker and some of the time at the worksite, 13 (5.8%) worked as a teleworker for a few weeks to 3 months and then returned to the worksite, and 17 (7.6%) had other experiences, including returning to the worksite after more than 3 months had passed.

Two thirds — 201 of 302 participants who teleworked — reported changes in how they worked because of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as having meetings using Zoom. When asked to select the changes they experienced, 200 participants selected at least one change, including:

- Attending meetings, conferences, or workshops online (n=152)

- Having to learn to use at least one web conferencing tool (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams) (n=148)

- Starting to work from home (n=138)

- Using web conferencing tools in different ways than before the pandemic (n=120)

- Attending training online that before the pandemic they would have attended in person (n=116)

- Meeting with clients using online meeting tools (n=112)

- Presenting to others remotely (n=98)

- Working jointly on projects in which people are sharing their screens (n=92)

- Learning how to present remotely (n=89)

- Using file-sharing services (e.g., Google Drive) (n=78)

- Using visual interpreting services in a different way than before the pandemic (n=37)

- Learning to use file sharing (n=33)

- Using instant messaging tools in a different way than before the pandemic (n=29)

- Having to learn to use instant messaging tools (e.g., Slack) (n=18)

- Learning to use visual interpreting services (e.g., Aira) (n=14)

- Experiencing technology challenges at the worksite due to pandemic protocols (n=12)

Workers may not have an option when it comes to where they must work. However, the researchers wanted to know if participants, given a choice, would want to continue teleworking post-pandemic based on their experience with technology during the pandemic. Of 190 teleworker respondents, 74 (39.0%) strongly preferred or preferred to continue to work from home and 86 (43.3%) preferred or strongly preferred to return to the worksite.

Accommodation Requests During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many workers made a quick shift from working at a worksite to working at home. Fifty-three (27.5%) of 193 participants requested accommodations from their employer as a result of becoming teleworkers. In an open-ended question, participants were asked to describe their experience requesting accommodations. Accommodations requested included having access to assistive hardware or software at home (e.g., screen reader software, braille display, large monitor) and assistance setting up videoconferencing applications. Six participants also requested permission to stay home after other employees returned to the worksite due to their health conditions increasing their risk for COVID-19 or a perception that their visual impairment put them at greater risk than others. Most participants reported that their accommodations were granted with little difficulty; however, a few reported facing delays or denials when requesting accommodations.

Technology Challenges During the COVID-19 Pandemic

In an open-ended question, participants were asked to describe the three greatest technology challenges they experienced during the pandemic. Many of the challenges cited involved the inaccessibility of videoconferencing. While these challenges were more widespread during the pandemic, they were already present for workers with visual impairments. With greater numbers of workers who are blind, have low vision, or are deafblind using videoconferencing, challenges were discussed and documented more often. Additionally, some participants reported difficulty getting IT support or sighted assistance with accessing materials when colleagues or IT staff were not in the same physical space. They described the frustration of needing to wait for remote support instead of quickly receiving in-person support.

"Zoom has been a big challenge, especially the screen-sharing. I struggle when teaching students via Zoom because it is hard for me to see the screen that they are sharing. It is also hard to keep up with the chat functions. This leaves me always feeling behind my colleagues." —White female in her 20s who became visually impaired in childhood

Benefits of Teleworking for Employees Who Are Visually Impaired

"I’m able to work a lot better at home just because it’s more predictable but also because I’m not impacted by people seeing the magnifier and saying, ‘Wow your font’s so big!’ or “Wow why are you doing it that way?’" —Black female in her 40s

Participants who were teleworkers also spoke of the positives they experienced. These included not having to travel to and from a worksite, having equipment set up in a way to maximize their productivity, not having auditory distractions, not feeling that one’s screen reader was disrupting others, and not experiencing actual or perceived discrimination because of their visual impairment. Some participants felt that their visual impairment was less noticeable or not known to others at all when meeting remotely.