"Coming to a new company as somebody who has accessibility needs is usually a nightmare[….] to navigate processes that are optimized for the 99th percentile and they just don’t know how to handle people who have different needs." —White male in his 40s who became visually impaired as an adult

There were some survey and interview participants who never made an accommodation request because they reported they did not need accommodations, had accommodations already set up prior to hiring, were self-employed and thus had control over the equipment and accommodations needed, or feared denial or a negative reaction from the employer if they made a request.

As part of the hiring process, 317 participants shared one or more ways in which they went about requesting accommodations when hired. These included:

- Talking to a supervisor to help them understand individual needs (n=156)

- Working with coworkers to help them understand individual needs (n=151)

- Asking an employer to purchase needed AT software (n=138)

- Working with IT staff to help them understand individual needs (n=134)

- Talking with HR staff to help them understand individual needs (n=104)

- Asking an employer to purchase AT hardware (e.g., braille embosser, CCTV/video magnifier) (n=95)

- Working with IT staff to integrate AT software with mainstream or proprietary software (n=73)

- sking an employer to purchase workstation accommodations (e.g., adjustable monitor arm) (n=51)

"With my work computer being a 'managed device,' it was very difficult to obtain approvals to get ZoomText installed as it required ADMIN rights and wasn’t on their list of approved software. Getting IT to assist and bypass approvals was very difficult at the time." —White male who became visually impaired as an adult

The researchers wanted to examine the current accommodations workers use. Participants were provided an extensive list of accommodations and asked to select all that applied to them. There were 317 participants who selected at least one accommodation. The mean number of accommodations selected was 5.9 (SD=3.1). The 12 most frequently selected accommodations were:

- Screen reader software (n=216)

- Built-in screen reader (n=174)

- Sighted assistance (n=173)

- Built-in voice assistant (n=136)

- OCR software (n=117)

- Built-in visual features of the computer (n=108)

- Refreshable braille display (n=108)

- Large monitor (n=93)

- Screen magnification software (n=84)

- Braille notetaker (n=79)

- Visual interpreter service (e.g., Aira, Be My Eyes) (n=78)

- Changes in lighting (n=65)

"It's uncomfortable [to ask for accommodations] because I don’t think they're knowledgeable about the needs of blind and visually impaired people." —Hispanic/Latinx female in her 50s who became visually impaired in childhood

Thirty-eight of 126 participants with additional disabilities or health conditions reported requesting an accommodation for their additional disability(ies) or other health condition(s). Examples of accommodations requested by participants with additional disabilities included: flashing phones or fire alarms for those who were deaf or hard of hearing, changes in lighting to accommodate those who experienced migraines, and changes to the environment, such as lowering materials or installing a ramp, for those with physical disabilities.

The researchers wanted to understand under what conditions employees made accommodation requests. At least one of the following responses was selected by 278 participants:

- During the hiring process (n=150)

- When given new work responsibilities (n=121)

- When new technology was introduced by the employer (n=115)

- When the participant learned of new accommodation options (n=71)

- When the participant experienced a change in vision (n=48)

- When the participant experienced a change because of another disability or health condition (n=23)

Rights and Responsibilities The law requires employers, in a timely manner, to provide and pay for accommodations that employees need to perform their job. Although the law allows an exception for an accommodation that would pose an "undue burden," it is a high threshold for employers. The employer may work with an employee to provide alternative but effective accommodations in such cases. The accommodations process should be iterative and tailored to the unique needs of the employer, the individual employee, and the job.

Table 4 shows who participants typically requested accommodations from and what occurred when the employee made accommodation requests after they were hired. In addition to the data in the table, there were four participants who reported they were reassigned to a new position because of their request for accommodations.

Table 4: Persons From Whom Accommodations Were Requested and Their Responses

| Accommodations Provided (n=211) | Accommodation Requests Questioned (n=35) | Job Responsibilities Restructured (n=16) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisor/Dept. representative | 126 | 19 | 6 |

| HR staff | 24 | 9 | 6 |

| IT staff | 27 | 0 | 2 |

| Office for employees requesting accommodations | 23 | 6 | 1 |

| Other | 11 | 1 | 1 |

"My latest request was for Aira. It took two years to approve this request. Numerous battles with the legal department regarding nondisclosure agreements resulted in reducing where I can use the service. I eliminated my responsibilities as a coordinator as a result. There are still a few other areas where I am not allowed to use this service, but HR has provided no alternative other than using fellow employees." —White female in her 60s who is congenitally visually impaired

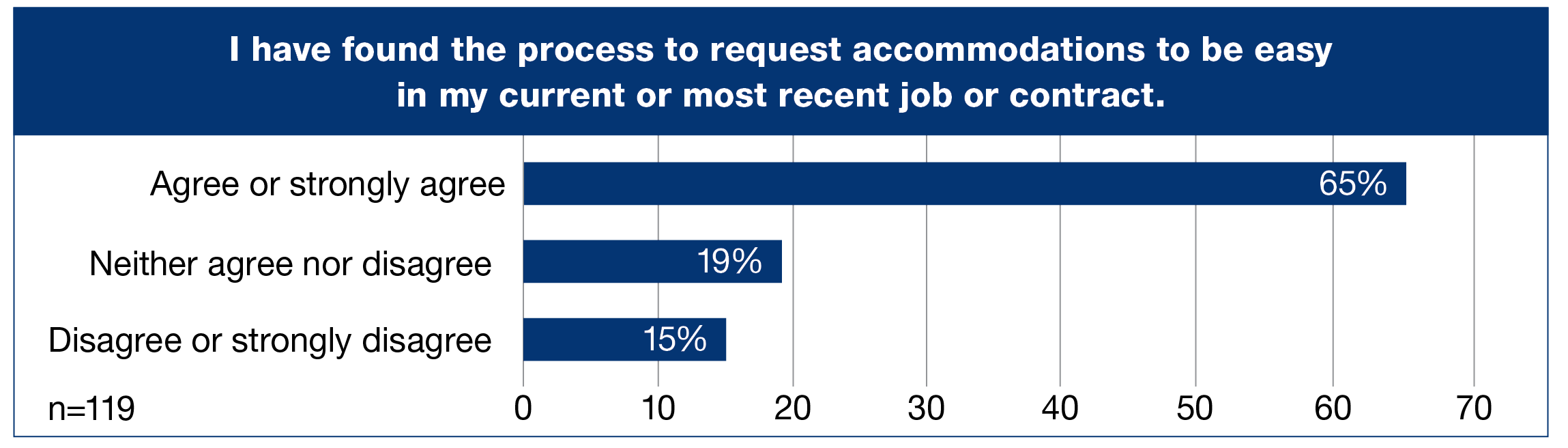

Participants were asked to select their level of agreement with the statement: I have found the process to request accommodations to be easy in my current or most recent job or contract. Of the 119 participants who responded, 78 (65.5%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. However, another 18 participants (15.20%) disagreed or strongly disagreed, suggesting that they experienced difficulty.

Figure 4. Ease of Requesting Accommodations

In an open-ended question, participants were asked what additional accommodations they believed would allow them to perform their work responsibilities more efficiently. The most mentioned accommodations were:

- multiline braille displays or other improvements to the smooth functioning of braille displays (n=24)

- artificial intelligence (n=18)

- some form of smart glasses (n=17)

- an indoor GPS (n=9)

- some form of visual interpreting service (n=7)

Technology Products Used by Participants in a Typical Week

Job responsibilities for almost all employees require some use of technology. The combination of mainstream and AT can increase a worker’s productivity, but if the products do not work well together, a worker’s productivity can be decreased. In the same vein, those who do not use AT but have low vision and use built-in features of software may not use the software as efficiently as they could, and thus their productivity is decreased.

Participants in the survey and interviews provided a wealth of information about the work tasks they completed and the technology tools they used. The technology tools used in a typical workweek, as reported by 308 participants, are:

- Email (n=293)

- Browsing the Web (n=284)

- Word processing (n=284)

- Web conferencing (n=270)

- Accessing PDFs (n=242)

- Spreadsheets (n=208)

- File sharing (n=182)

- Instant messaging (n=142)

- Presentation tools (n=118)

Most of the participants reported using Microsoft products: of the 284 who reported using word processing, 267 used Microsoft Word; of the 115 who reported using presentation tools, 106 reported using PowerPoint; and of the 208 participants who used spreadsheets, 195 used Microsoft Excel. Smaller numbers of participants reported using Google products (n=26 for Google Docs; n=31 for Google Slides; and n=58 for Google Sheets). Google products were used more frequently than Apple products: only 26 participants reported using Pages; 10 used Keynote; and 13 used Numbers. Of 285 participants, 170 reported using only Microsoft products, 6 reported only using Google products, and 6 reported only using Apple products.

To use mainstream technology, people who are blind or have low vision often have to find workarounds as described in the section in this report on efficiency. The quote on the next page describes the multiple challenges faced by a screen reader user. The extent to which a user relies on workarounds reflects the accessibility of the tools they are using, the adequacy of their training, and the commitment of their coworkers to use shared tools and programs in an accessible manner.

"Two challenges across the board for all applications are navigating the menus…and controls not indicating status. Using JAWS means you have to look at each item in a menu and remember where it is when you want to find it again…Sometimes when I use the JAWS cursor to read the title bar or other toolbars, it says nothing. Often you can’t tell what is selected, if a checkbox is checked or not, etc.…In particular, I have trouble formatting documents in [Microsoft] Word. I write in Notepad then paste into Word so I can apply the formatting I want because it is too hard to adjust the existing Word format. I also paste Word documents into Notepad to strip the formatting before pasting into Duxbury [a braille translation program] for brailing. The worst thing in Word is using track changes and comments. When receiving a marked-up document, I can’t tell what’s old and what’s new. I can’t consistently find the comments. Entering my changes just adds to the nightmare." —Multiracial female in her 50s who became visually impaired in childhood

Additional mainstream products that participants mentioned specifically by name were Zoom, Webex, Dropbox, Discord, Microsoft Outlook, Microsoft Office 365, Microsoft Teams, GoToMeeting, BlueJeans, Mozilla Firefox, BRAVE, Edge, Google Meet, Google Classroom, Amazon Chime, Salesforce, and Amazon WorkDocs.

Participants were asked what email client they used in a typical workweek. The 293 participants were more varied in their email use. There were 242 who used Microsoft Outlook, 143 who used Google Mail, and 75 who used Apple Mail. One hundred forty-five participants reported only using one of the three email clients, while 117 reported using two of the clients, and 26 reported using all three email clients. Participants were not asked to provide information on whether they accessed their email via a mobile device or computer.

Participants were asked which web browsers they used in a typical workweek. Similar to email, there was variability in the web browsers they used. There were 239 participants who used Chrome, 149 who used Safari, 87 who used Firefox, 83 who used Edge, and 41 who used other browsers such as Internet Explorer. Eighty-one participants reported only using one web browser, while 122 reported using two web browsers, 55 reported using three web browsers, and 17 reported using four web browsers. Regardless of what web browser they used, participants had challenges accessing websites that were not accessible to them or compatible with their assistive technology3. Screen reader users experienced issues such as headings not being used, unlabeled checkboxes and buttons, and image descriptions not provided. Low vision users described issues such as poor color combinations, difficulty telling where buttons are located, text written over images, and poor organization of information.

One hundred thirty participants reported on the instant messaging tools they used. Forty-one participants used Google Chat, 36 used Slack, and 70 used other messaging programs. Due to an error with the survey, participants were not able to list the other tools they used. Several participants pointed out that Slack was accessible with an iPhone, but not with the desktop client for those using screen reader software.

File sharing was a task reported by 175 participants. In a typical workweek, 91 used Dropbox, 87 used Google Drive, 76 used Microsoft OneDrive, 16 used Box, and 20 used other file-sharing tools.

Preparation and Usability of Work Products

In addition to accessibility, there is also a question of usability. The way the creator structures a document, spreadsheet, presentation, PDF, website, or app affects the use of the item by those with visual impairments. Though not every individual will experience the same challenges, challenges described by participants included:

- Difficulty accessing material containing unlabeled graphics

- Google Docs being less efficient than Microsoft Word due to single-stroke table navigation commands and general sluggishness

- Sharing documents, especially for those using screen reader or screen magnification software, causing issues with navigation and editing

- Difficulty with navigating large spreadsheets for both screen reader users and those with low vision whether or not using screen magnification software

- Requiring training or more time to learn keyboard shortcuts compared with sighted coworkers

"We do Zoom meetings with our corporate office. They show things on the screen and refer to them. My coworkers are great at describing these things, but these materials are never provided to me in advance." —Hispanic/Latinx female in her 30s who became visually impaired as an adult

Web Conferencing

Web conferencing tools have been used more widely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of 268 participants, in a typical workweek, 239 used Zoom, 116 used Microsoft Teams, 63 used Google Meet, and 52 used Webex.

When asked to describe their biggest challenges with technology during the COVID-19 pandemic, participants described a wide variety of challenges. One common theme was difficulty with videoconferencing applications. In examining the comments, the following issues were described in reference to web conferencing:

- Content shared from another user’s screen is inaccessible to screen reader users when it is represented as an image.)

- For those with low vision, content shared by others may be difficult to enlarge or manipulate.

- For those with low vision, it is difficult to view a videoconference while also viewing another window, for example, a document the speaker is referencing.

- Navigating and using Teams was difficult for some screen reader users, including knowing what one’s last message was or where to find a file that may not be readable.

- When using a screen reader in Zoom, the program speaks participants’ names as they enter and leave the room which can be distracting.

- Difficulty muting and unmuting when using a screen reader.

- In Webex, use of the chat feature was difficult or impossible for some participants.

"The biggest challenge for me has been to use our electronic health record system for videoconferencing and to do teletherapy counseling sessions. It has been difficult to know if I am on camera, and to ensure the system is working and there [are] no[t] technology issues. This is done with JAWS on a Windows PC and Google Chrome." —White female in her 30s who is congenitally visually impaired

Compatibility of AT and Mainstream Products

Participants in our survey and interviews provided examples of situations in which their mainstream technology and AT did not work together effectively. We found that many participants solved problems for themselves rather than seek support from IT staff when there was a compatibility issue with their mainstream technology and AT. For example, they posted questions on listservs, did online searches for information, contacted other AT users, used visual interpreting services, and read manuals.

"[The time tracking program used at my work], Workday will keep me out of the kingdom of Heaven because it gets me cussing and pounding. We just implemented it and it’s doable, but it takes a long time for me to do simple, simple things. If I want to take a vacation and do more than one day, the length of time it takes [to enter my information into Workday] is mentally taxing and morale destroying. They are aware of it [at my job]. We have people who are constantly trying to convince the Workday folks that 'This is what you have to do to beef this up.' I try myself first [to use Workday with my assistive technology as] it’s a pride thing, I gotta be able to do this. [Eventually] I will open TeamViewer and call the Aira agent [when] I can’t take it anymore. Then it takes mere minutes instead of hours [to use Workday]." —White male in his 70s who is congenitally visually impaired

Participants were provided a list of possible actions they may take when mainstream technology and AT do not work together. Three hundred three participants reported taking the following actions:

- Work with IT staff with expertise in troubleshooting compatibility issues or software changes (n=174)

- Work with staff from VR or a private agency (e.g., Lighthouse for the blind, local non-profit) in troubleshooting compatibility issues or software changes (n=40)

- Consult a contractor the employer hires with expertise in troubleshooting compatibility issues or software changes (n=36)

One hundred fifty-three selected "Other" and many of the participants indicated that they were primarily responsible for their own troubleshooting and used strategies such as collaborating with friends or coworkers who are also AT users; writing their own JAWS scripts, using a visual interpreting service or sighted person for assistance; and contacting vendors on their own.

A few self-employed participants chose not to share with their clients that they had a visual impairment. When they experienced challenges with mainstream and assistive technologies, they often would use a visual interpreting service to assist them with access, sometimes at the same time they were remotely working with a client.

Use of One’s Own Technology for Work

The participants were asked to select which personal technology tools they used to complete job tasks for which they did not have adequate accommodations, with multiple responses allowed. The 210 participants reported they used the following:

- A computer or laptop with screen reader software (n=88)

- A tablet (e.g., iPad, Android) (n=60)

- A braille notetaker or refreshable braille display (n=55)

- A computer or laptop with screen magnification software that also might have screen reader software (n=33)

- A CCTV or video magnifier (n=32)

Seventy-one participants also reported that they used other things of their own that they used including paying for visual interpreting services, using a monocular telescope, and providing their own braille embosser. Twenty-six participants described using their own smartphone (or cell phone), with 18 specifically naming the iPhone, when they did not have adequate accommodations.

For most participants who used their own equipment when there were problems with their work setup, there had been no issue with their employer so far. It was understood that to get their job done they sometimes used their own equipment. Those who were self-employed had the ability to select which equipment they purchased and used. Nonetheless, in rare instances, employers would not allow employees to use their own technology.

Although participants often reported that they used their own technology in our sample, this could be problematic for both employees and employers when it comes to security and privacy concerns, IT support, control of employer work product, and legal issues. Using their own technology may resolve individuals’ immediate issues, but it does not absolve an employer of their duty to provide adequate accommodations to perform work tasks.

One participant who was interviewed shared that when he provided his own magnifier and was using it in front of a client, the CEO stopped the meeting and fired the employee for using equipment that caused the client to know he had a visual impairment.

In this example, presumably, the use of the participants’ own technology as an accommodation proved problematic for the employer, but the employer also failed in other aspects of its obligation to prevent discrimination against its employee with a disability.

3. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines offer industry best practices for designing websites and software to be accessible to and usable by people with disabilities, including those using assistive technology. https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/↩