Flatten Inaccessibility: Executive Summary

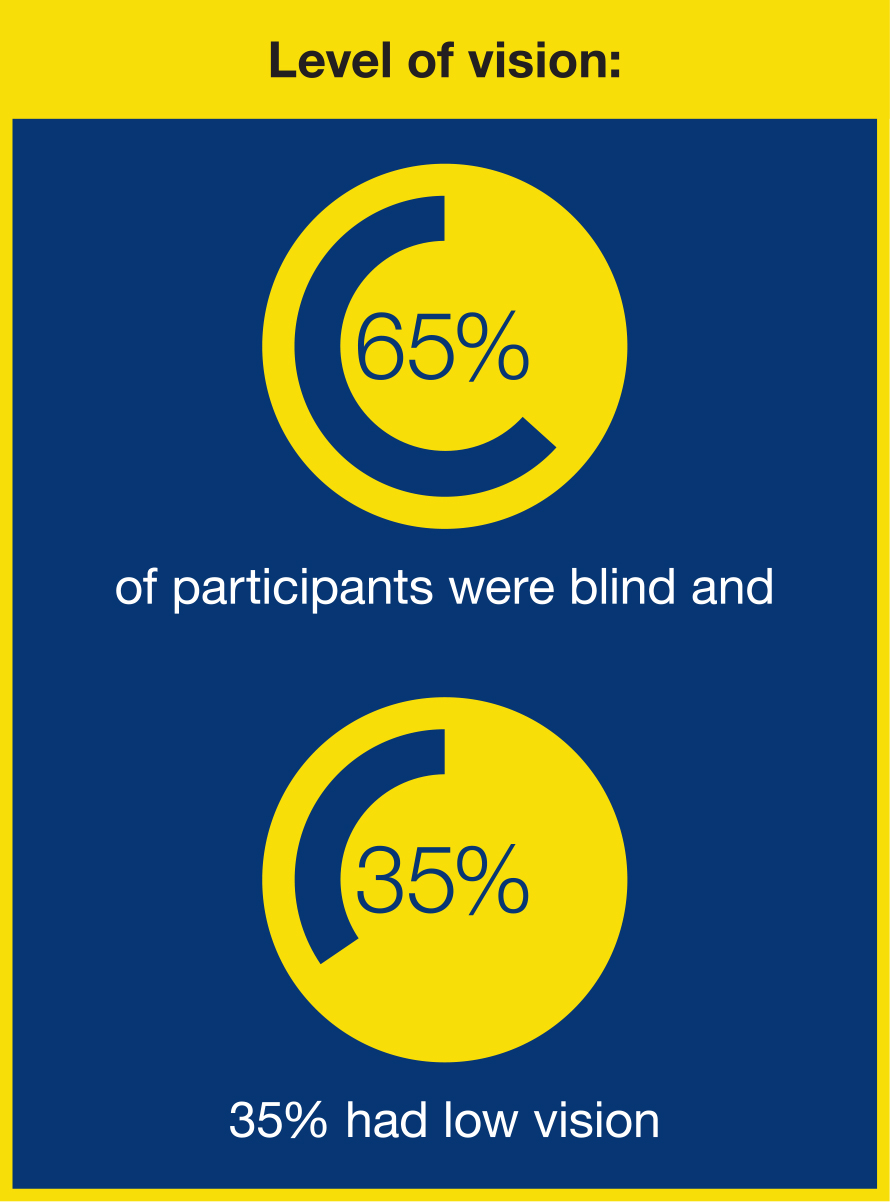

The Flatten Inaccessibility survey investigated the experiences of adults who are blind or have low vision during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This report summarizes findings from 1,921 participants on healthcare, transportation, employment, education, social experiences, access to food, meals, and supplies, and voting.

Participant Snapshot

- Location: All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico were represented

- Gender: Female, 63.4%; male, 35.2%; transgender or gender nonconforming, 1%; and no response, 0.37%

- Race or ethnic background: White, 77%; Hispanic, Latinx or Spanish Origin, 7%; Black or African American, 7%; Multiracial, 4%; Asian, 3%; American Indian or Alaska Native, 1%; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 0.11%; and Other, 1%

- Age distribution: 18–34 years, 23.5%; 35–54 years, 34%; and 55 and older, 42.5%

- Employment status: 29% were employed full time, 10% were employed part time, 3% had been employed full time and 6% had been employed part time prior to the pandemic, but were now unemployed, 29% had not been employed prior to the pandemic, and 23% were retired

- Living arrangements: 43.5% of participants lived with a spouse or partner, 33.6% lived alone, and 15.3% lived with other family members

- Technology use: 93.4% of participants had Internet access at home; 92% reported using a smartphone; 51.7% used screen reader software; 74.7% used social media; 68.2% used web conferencing tools; and 72% used online shopping apps

Key Areas of Concern

68% of participants had concerns about transportation, particularly related to safety, restricted access to transportation options (paratransit, public transit, taxis, rideshare), and fears they would not be able to get themselves or loved ones to COVID-19 test sites or healthcare providers if they were to get sick

54% of participants had concerns about healthcare, and 59% felt their underlying health conditions made them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 complications

56% expressed concern about social experiences; in particular, they had fears related to their ability to social distance, asking for help, asking for physical assistance, and using touch as they normally might (e.g., using tactile sign language)

59% of participants had concerns about their education due to their vision loss, with 35% reporting their rehabilitation center/agency had discontinued center-based classes, and 23% reporting they were no longer receiving in-home instruction

30% of participants reported meeting with their healthcare provider using telehealth, but 21% of these participants reported the telehealth platform was not accessible

47% of participants had concerns about employment, with 38% reporting accessibility problems with at least one of the technology tools needed to do their job and reporting they were unable to access technology at home that was essential for their job

Participants enrolled in higher education experienced access issues to online platforms and often did not have the accommodations for classes (e.g., braille) that they received on-campus

47% of parents/caregivers had concerns about their child’s education, with 60% reporting the technology tools they needed to use were not accessible and 90% reporting they received no training in the new technology

51% of participants had concerns about access to food, meals and supplies; in particular, they worried about unavailable items, lack of delivery slots, difficulty applying for food assistance, and food insecurity due to unemployment or reduced work hours

Although 91% of participants said they were registered to vote, 39% were unsure if they had an accessible voting system, and 23% reported they did not have an accessible system

Note: Please see the full report to assist in interpreting the percentages provided in this summary as the number of participants who answered any one question varied.

Our Recommendations

Technology

- Critical public health information must be accessible to people who are visually impaired.

- Grocery delivery services, Internet communications platforms, and telehealth should adhere to accepted accessibility standards such as the W3C WCAG.

- Provision should be made for visual interpreting services, such as Aira and Be My Eyes, for people with limited financial resources.

Transportation

- Transportation providers should establish community advisory committees that include people with disabilities, and they should work with local governments to offer alternatives for those who are disabled when services in a community are limited or discontinued in an emergency.

- Long-term investments should include transportation access in underserved areas, as well as sidewalks that connect people to services, transportation hubs, and their destinations.

- Drive-through or curb-side pick-up services, such as COVID-19 testing sites or food banks, must provide alternatives for those who do not have access to a vehicle.

Social Experiences

- Advocacy groups should launch awareness campaigns to explain the human guide technique and why someone with a visual impairment may not be able to maintain a social distance when using it or requesting assistance.

- Mental health providers need up-to-date training to better meet the specific needs of adults who are visually impaired.

- Game developers, exercise instructors, and website/app developers should build accessibility and usability into all offerings.

Healthcare

- Healthcare facilities must recognize that people with visual impairments may need someone to accompany them to visually interpret the environment when necessary and advocate on their behalf.

- Medical providers should make written information accessible to individuals who are visually impaired by providing electronic, braille, and large print options.

- Electronic health records, secure video platforms, and other telehealth systems should meet the highest accessibility and usability standards.

Access to Food, Meals, and Supplies

- Businesses should provide disability-specific training to employees to ensure people with disabilities are served appropriately; stores should provide specific hours for seniors or those with disabilities to shop; and online and app-based ordering platforms must be accessible to those who use screen reader or screen magnification technology.

- Home health companies, consumer organizations, policymakers, and others must work together to ensure home healthcare professionals receive training and follow all safety protocols.

- Online purchasing with SNAP and WIC benefits should be extended to every U.S. state and territory, and eligible retailers should be expanded.

Employment

- Companies must ensure recruitment and application platforms are accessible, and that employees are trained on new technologies and have access to technical support.

- Employers should ensure employees have access to comparable accommodations whether working from home or in the office.

- Employers should establish virtual meeting policies that may include providing materials to attendees in accessible formats, use of captioning or interpreters where appropriate, nonvisual communication techniques, and having individuals identify themselves before speaking.

Education

- Educational institutions must ensure visually impaired students and instructors are able to use all selected learning tools and receive accessible training in their use.

- Disability resource offices should have a plan for providing appropriate accommodations, accessible materials, and course access to students whether for live or online classes.

- Instructors should be given accessibility training and support to ensure they can create equitable learning experiences for all students.

Experiences Supporting Children in K-12 Education

- Schools must provide learning materials in alternative formats to accommodate students or their caregivers, and in the event that Internet access or appropriate devices are unavailable.

- Training and guidance on any online communication and learning tools should be provided in accessible format.

- Any accommodations a child receives in the classroom through an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 Plan should follow the child home, or alternative accommodations should be provided.

Voting

- Voters must be provided with options that allow for independent and private voting at the polls or at home.

- Accessible voting machines must be available at all polling locations, and workers must be trained on their use so they can provide instruction to voters as needed.

- Remote voting options must be accessible, secure, and widely available.