Access and Engagement II: Executive Summary

Executive Summary

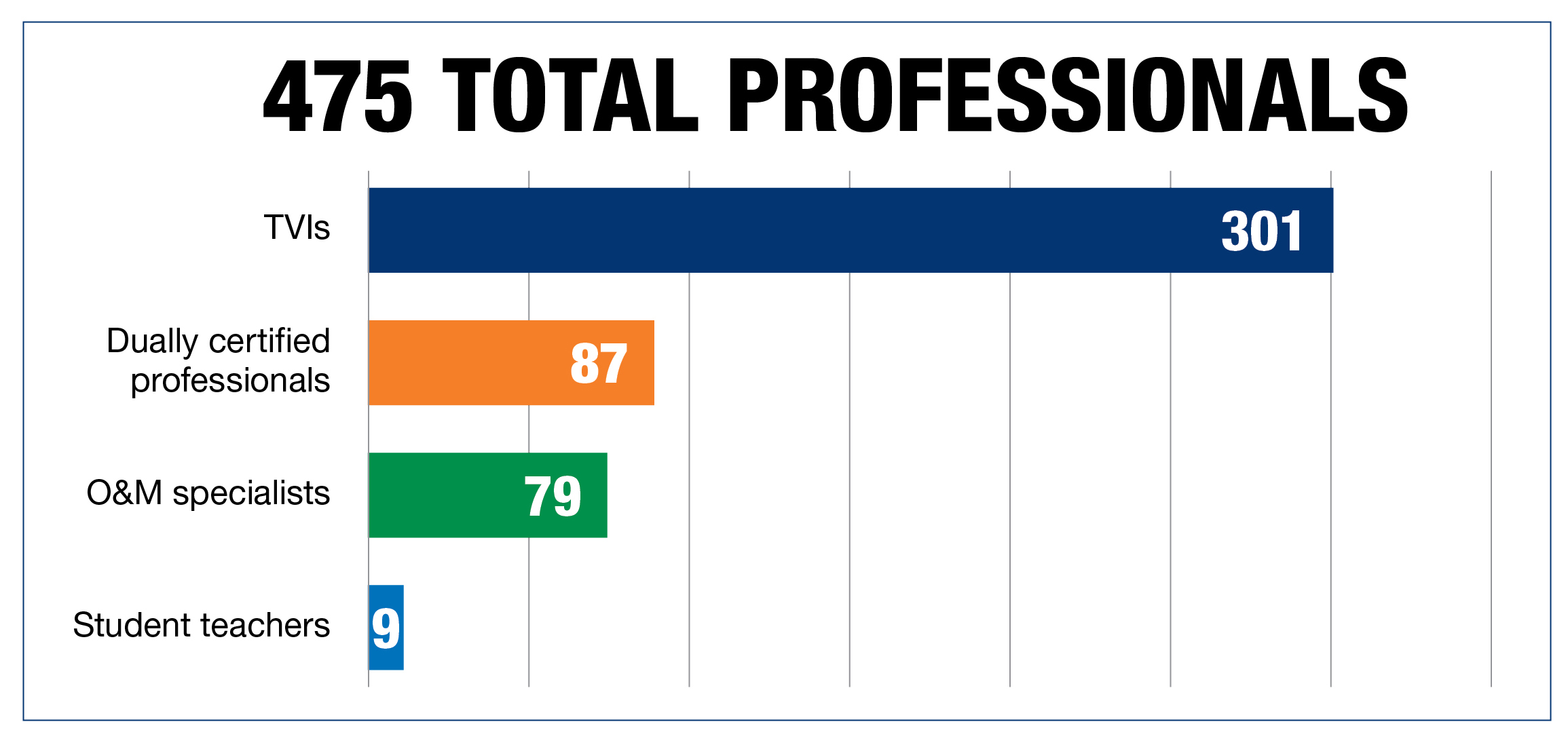

The Access and Engagement II study investigates how the education of students with visual impairments in the United States and Canada was affected nine months into the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, a follow-up to the first study in April and May 2020, we continue to document the systemic and pandemic-related ways in which children (birth to age 21), their families, teachers of students with visual impairments (TVIs), orientation and mobility (O&M) specialists, and dually certified professionals have been affected.

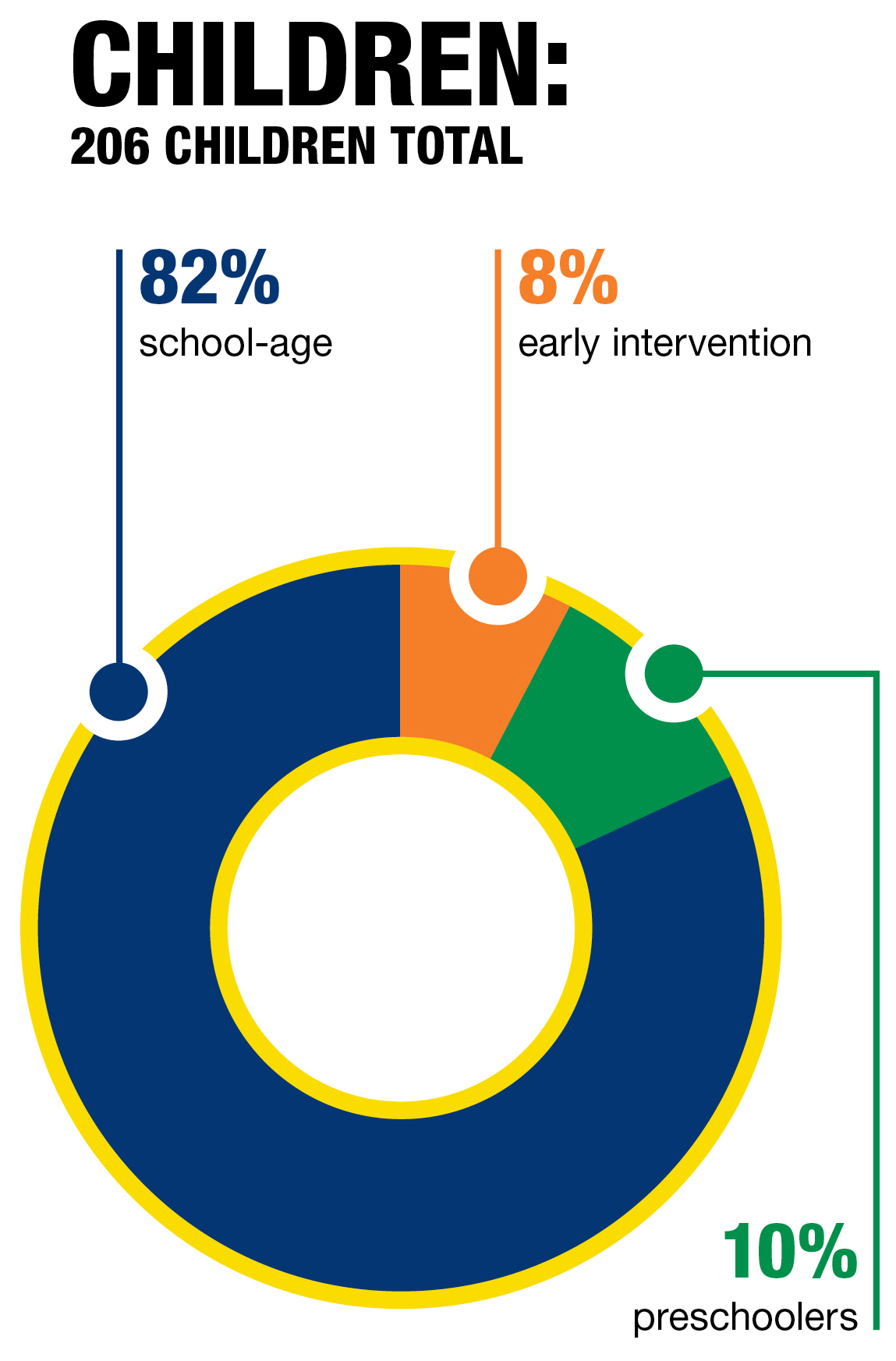

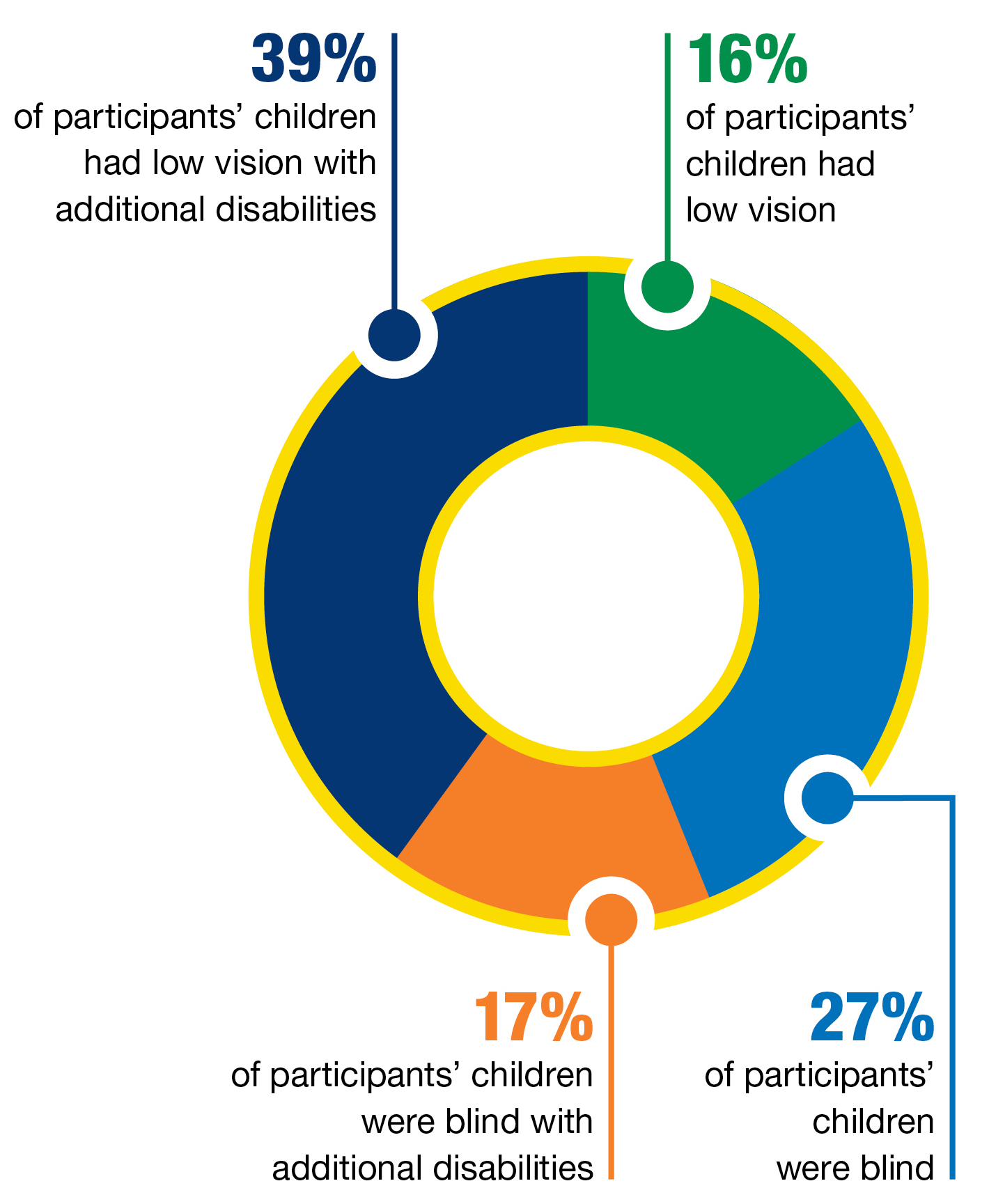

The 662 participants represented 206 children with visual impairments, including those with additional disabilities and deafblindness, and the specialized professionals skilled in providing educational services to meet those students’ diverse needs.

Participant Snapshot1

- 48 U.S. states, 6 Canadian provinces, and 1 overseas U.S. school were represented.

Key Findings

Regardless of where early intervention services were delivered, most family members reported feeling overwhelmed, especially as they needed to juggle multiple roles.

Some family members of preschool-aged children found that changes from online to hybrid to in-person made it difficult for their child to learn, but others found that during the pandemic, their child’s skills were increasing.

Although it is probable some changes in children’s skills were not due to the pandemic, the deep decline in the types of services (e.g., physical therapy, O&M) that school-aged children received compared with before the pandemic is telling.

By November 2020, more children were receiving educational services than in spring 2020.

As of November 2020, 58% of professionals were able to reach between 90% and 100% of their students’ families; with 42% of professionals reaching less than 90% of students’ families.

Four out of 10 professionals reported that up to 25% of their students were on the low end of the digital divide.

Two-thirds of the professionals reported they had worked with either an IFSP and/or IEP team to make changes to one or more students’ IFSPs or IEPs due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Family members and professionals reported that many apps and websites were inaccessible or not fully usable for students who were blind or had low vision. Chromebooks especially presented accessibility challenges.

During the pandemic, many TVIs reported it was challenging, if not impossible, to coordinate with the classroom teacher in order to prepare and/or get materials to students attending school virtually in time for the lesson.

Our Recommendations

The Importance of Teamwork

Communication between students, family members, vision professionals, other educators, and administrators must be ongoing, clear, and individualized to the needs of the student and family members.

Family members and students who do not speak English as their primary language need access to interpreters. The move to online platforms nor budget constraints must not stand in the way of providing family members and students access to interpreters.

Vision professionals who are experts in their fields must be acknowledged and have the time and resources to meet their students’ diverse needs.

Student success requires the family’s basic needs be met for there to be investment in the child’s education.

Ensuring Full Participation in Education

Administrators must be willing to work with educators to designate funding and resources, so that all students who need services are provided with such.

Policymakers and administrators should examine the caseload sizes of vision professionals and plan for hiring new staff to adjust caseload sizes while maintaining service levels.

Assessments must continue to occur as required by the Individuals Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and individual student needs. Administrators and policymakers should develop strategies to ensure assessments are completed in a timely and effective manner.

Partnering with community agencies allows school districts, specialized schools, and other educational agencies to ensure materials are available in the native language of family members or interpreters can translate so family members and educators can engage in meaningful dialogue.

Full Access to Digital Learning

Students and families must have adequate Internet availability in order to participate in online education.

Students must have access to the same technology at home that they have access to at school.

Instruction and ongoing support with technology, including replacing and/or repairing technology in a timely manner, must be provided to students, families, and educators.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) should implement the Emergency Broadband Benefit with a focus on device accessibility and outreach to people with disabilities and their families. The Benefit, or a similar program, should be made permanent after the public health emergency ends. Additionally, Congress and the FCC should consider a permanent expansion of the E-rate2 program to afford schools and libraries the flexibility to serve students learning from home.

Technology companies must use inclusive design principles from conceptualization through production of a digital learning tool.

State or provincial governments should work with school administration and technology companies to ensure products provided to educators and students are accessible.

Providing Access to the Curriculum

Students with visual impairments must have access to instructional materials at the same time as their peers.

Administrators must provide adequate time for educational teams to develop and implement accommodations that ensure students full access to the curriculum.

Administrators should institute appropriate processes and allocate sufficient funding to allow to accommodate students with appropriate supplies, including using federal COVID-19 relief funding when available.

Vision professionals need to have access to the same technology their students use so they can develop lessons and have the knowledge to support student learning.

Policies and procedures must be in place to ensure braille readers have hard copy braille.

Supporting the Mental Health and Safety of Students, Families, and Professionals

Administrators, vision professionals, and other educational team members should seek new ways to strengthen home–school partnerships moving forward.

Vision professionals and other educators need support from administrators to maintain a healthy work–home balance, maintain their productivity, and not burn out and leave the profession.

Additional staff, including guidance counselors, psychologists, and social workers, must be available to students, families, and all educators both on a short-term and long-term basis, as necessary.

Many students, family members, and vision professionals were feeling stressed, overwhelmed, or anxious due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The provision of counseling and other supports needs to occur even once in-person learning returns to pre-pandemic levels.

Supporting Student Success

Additional funding for expenses such as COVID-19 mitigation, staffing support, and Extended School Year (ESY) services may be needed for more students than are typically served in a school year.

Administrators must provide vision professionals with additional time to conduct assessments under COVID-19 restrictions.

Administrators and educators must build on the successes of student lessons vision professionals have developed and the ways in which they have coached family members during the pandemic.

Final Thoughts

As we move into post-pandemic education, family members, vision professionals, other educators, administrators, and policymakers must work collaboratively to ensure that students’ basic needs are met, and their skills do not regress. We do not yet know the short-term and long-term impacts of the pandemic on individual children nor do we know how to provide all children with visual impairments with an individualized and appropriate education while also ensuring students’ social-emotional well-being during a disruptive event such as a pandemic. We do know that until students have fully accessible, inclusive learning opportunities with the necessary supports, their ability to learn and maximize their full potential is at risk. Together, policymakers, administrators, educators, family members, and students have the opportunity to take lessons learned during the first nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic to shape the future of education for our students with visual impairments, including those with additional disabilities and deafblindness.

1. Please see the full report to assist in interpreting the percentages provided in this summary as the number of participants who answered any one question varied.

2. https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/universal-service-program-schools-and-libraries-e-rate