Many problems are simply exacerbated by distance learning. Those with visual impairments need in-person and often hands-on instruction. It takes a village, and many students don’t have a village to support them. —White female TVI

There were 710 professionals who reported that they only worked in the role of TVI during the 2019-2020 school year and 180 dually certified professionals who worked both as a TVI and an O&M specialist during this school year. Unless otherwise specified in this section, the researchers have opted to combine the data of these two groups and refer to these 890 professionals as TVIs.

Delivering TVI Services Outside a School Building

Across the United States and Canada, there is variability in how TVIs were providing services in spring 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic and what their administrators were or were not allowing them to do. From a list of four choices, TVIs were asked to select all the ways in which they were serving students and their families. At least one choice was selected by 765 TVIs. TVIs were:

- Given the option to decide how they provided services (e.g., delivering packets, phone calls, meeting online) (n=560)

- Given the choice about how much service time to provide each student on their caseload (n=248)

- Told they had to continue to provide the same number of minutes of service to their students as specified on each student’s IEP (n=122)

- Only providing support to their students in their general education classes (n=94)

The TVIs were asked what percentage of their direct service students and/or their family members they were currently meeting with online. The question did not refer to service hours on the IFSP or IEP. Of 890 TVIs, 237 TVIs reported that they provided services in more than one mode (e.g., as an itinerant and early intervention/preschool teacher). Table 14 presents the data by setting in which the TVIs worked. Between 10% to 15% of TVIs were not meeting with any of their students, while 50% to 60% of TVIs were meeting with more than 50% of their direct service students online. Some TVIs provided reasons why they were not meeting with their students and/or family members online. These included the fact that the district did not allow for online meetings, students and family members did not have the technology to meet online, and family members could not be reached once the school building closed.

Table 14: Percentage of TVIs, by Mode of Delivery, Who Reported Meeting Online with Direct Service Students

| Percentage of Direct Service Students | Itinerant (n=618) | Resource Room (n=91) | Specialized School (n=102) | Early Intervention/ Preschool (n=179) | Private School (n=33) | Other (n=58) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No students | 8 | 10 | 17 | 6 | 15 | 14 |

| Less than 25% of students | 20 | 10 | 12 | 18 | 20 | 14 |

| 26% to 50% of students | 18 | 24 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 19 |

| 51% to 75% of students | 18 | 16 | 18 | 25 | 18 | 10 |

| 76% to 99% of students | 19 | 16 | 18 | 24 | 18 | 10 |

| All students | 17 | 24 | 25 | 19 | 16 | 33 |

The TVIs reported that using technology to connect with their students and their family members was often positive. The technology allowed them to see how their students were progressing, share resources with family members, and provide family members with ideas for instruction. For academic students, technology allowed the TVIs to ensure students had the materials they needed to participate in their classes, to answer questions, to introduce new material, and to troubleshoot with students and/or family members. However, interactions via technology also caused some TVIs to express frustration and/or concern for their students.

The human touch is so important and difficult to duplicate with tech[nology]. The importance of relationships between educators and their students’ parents is huge and needs to be nourished, especially after this. —White female TVI

Access to Materials

Both teachers and students must have access to materials for students to actively participate and be engaged in learning. The TVIs were asked if they had all the materials they needed at home to serve their three types of direct service students. Table 15 shows the percentage of TVIs who reported that they had the materials they needed to meet their students’ needs. The number of TVIs providing responses varied, and therefore is not included in Table 15. In all employer categories, more TVIs reported having materials for their academic students with low vision compared with students who were blind or had additional disabilities.

Table 15: Percentage of TVIs Who Reported They Had All the Materials Needed to Support Students

| EMPLOYER | Blind Academic Students | Academic Low Vision Students | Students With Additional Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public School District | 48 | 71 | 54 |

| Cooperative | 47 | 52 | 48 |

| Specialized School—Campus | 52 | 68 | 56 |

| Specialized School—Outreach | 59 | 86 | 68 |

| Contractor Through a Company | 50 | 79 | 63 |

| Self-employed | 44 | 73 | 51 |

| Other | 53 | 63 | 60 |

A limitation of the survey was that TVIs were not also asked if their students had all the materials they needed to take part in education. When asked to describe what materials were not available to them at home to support their students who were blind and participate in academic curriculum, TVI responses primarily focused on materials to prepare hard copy braille for their students, materials to adapt academic subject content, and hands-on learning materials their students did not have at home. For example, TVIs reported that their students did not have access to hands-on manipulatives for science or math instruction (e.g., APH products such as the Draftsman or materials in Math Builders kits).

At the school, if a particular lesson required the use of an APH item (say, the fractions kit), I would pull it off the shelf and use it. Most of that material is still at the school and even if we could pick it up, the families neither have the space or inclination to try to keep up with all of that ‘stuff.’ Lessons are put up with no lead time to adapt and in week 4 we are still trying to work out the logistics. —White female TVI

Materials TVIs reported they needed to serve their students with low vision included the tools their students used to access print such as computers with screen magnification software, video magnifiers/CCTVs, reading stands, and lighting. Some TVIs did not have access to a copy machine so they were not able to enlarge materials provided by classroom teachers for their students. TVIs reported that the Chromebooks provided to some of their students by the school district were not accessible to the students because they lacked the features that allowed their students to access content on the screen. TVIs worked to find ways in which they could support their low vision students who did not have needed accommodations at home.

The students and I do not have access to their low vision devices so we cannot do the lessons we normally would. I am creating some materials and emailing them or doing a porch drop for those who have no access to technology.…I am joining…[others]…in their digital classrooms to see how they are doing and offer suggestions to the staff. —White female TVI

When asked about materials they did not have at home that they needed to serve their students with additional disabilities, TVIs reported that many of the materials they needed were designed for a specific student (e.g., experience books, calendar systems). They described augmentative or alternative communication tools students did not have at home such as switches. In some cases, TVIs were able to send home these materials ahead of time, mail them, or drop them off to the family. Many TVIs reported that online instruction was not appropriate for their students with additional disabilities who required one-on-one hands-on instruction.

Working with students who have multiple impairments requires one’s 'presence.' I cannot do that online. Some of my students struggle to maintain alertness. We typically use materials that promote orientation and on good days, activity. IEP objectives have to be tweaked to the point they no longer resemble the original. Sorry—you hit a sore spot. —Female TVI

Methods Used To Meet Students’ Educational Needs

TVIs are trained to provide their students individualized instruction and support based on their visual, tactile, and auditory abilities; their IFSP or IEP goals; the accommodations they need to access instructional materials, and their learning style, among other characteristics. The TVIs were provided an extensive list of ways in which they could meet their students’ needs. TVIs selected between 1 and 21 options with a mean of 5.20 (SD=4.78). The 10 options selected most by TVIs include:

- Sending resources to students’ family members (e.g., websites, videos, blog posts) (n=454)

- Calling on the telephone and speaking with family members (n=448)

- Texting with family members (n=398)

- Meeting online with family members (n=370)

- Meeting online (e.g., through Zoom) with students and/or family members to watch students complete a task (e.g., reviewing a tactile daily schedule) (n=345)

- Having students complete TVI-created assignments that target students’ IEP goals (n=289)

- Preparing braille materials for students (n=267)

- Sending family members videos to watch with their child (e.g., family-friendly videos for a child with CVI, how to fold money) (n=254)

- Meeting online with students to provide them access to materials used by their classroom teachers (n=237)

- Meeting with students to review assignments that their classroom teachers have provided (n=236)

Working with General or Special Education Classroom Teachers

Four hundred eighty-five TVIs reported that they had students who were currently attending general or special education classes online. Four hundred fourteen TVIs reported having at least one challenge with classroom teachers. Their responses included that classroom teachers were:

- Using websites, apps, or online programs that were not accessible to students (n=200)

- Recording videos that were not accessible to students (n=91)

- Not having time to meet with the TVI to discuss accommodations needed by students (n=72)

- Not providing students work or only providing “busy work” (n=47)

- Fcusing instruction, as per administrator directive, on students without IEPs or 504 Plans (n=11)

In addition to selecting one of the provided responses, when asked what other challenges they were experiencing related to classroom teachers, 228 TVIs shared details about how they were working to ensure that their students had success in their general or special education classes.

Trying to help my academic blind students keep up with work when all teachers are using Google Classroom in different ways and much of the work given is in inaccessible forms has been very challenging. I worry most about the students with multiple disabilities because my instruction needs to be hands on. But so many have health issues, there is really no way around this. —White female TVI

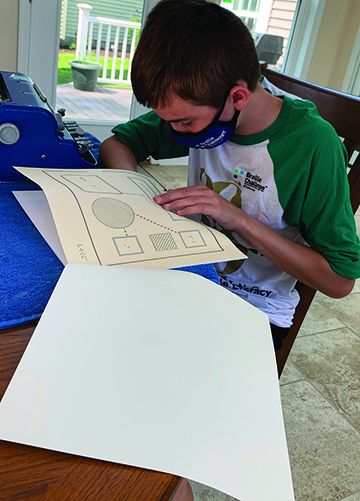

Supporting the Education of Pre-Braille or Braille Readers

TVIs often meet daily with students learning braille to provide individualized instruction as specified through their IEP goals. Young children who are in the emergent literacy stage need systematic instruction to build both skills with the code and the ability to read and write (Chen & Dote-Kwan, 2018) 20. As children acquire braille literacy skills, it is imperative that they receive appropriate instruction and adequate time with the braille code to yield the most positive outcomes for their future (Penava et al., 2017) 21. TVIs incorporate time into their weekly schedule to instruct lessons, adapt printed material, and support students to ensure they can access the curriculum.

Four hundred thirty-five TVIs reported that they served at least one student who was a pre-braille or braille reader. Thirty-two TVIs indicated that due to COVID-19, they were no longer allowed to prepare braille materials for their students. When asked how they were supporting their braille readers during COVID-19, 417 TVIs selected at least one option. TVIs were:

- Preparing braille materials and either delivering them to students’ homes or having a family member pick up the materials (n=138)

- Preparing braille materials and mailing them to students’ homes (n=160)

- Enlisting the help of others to assist in the preparation of braille materials (n=103)

- Preparing braille materials and sharing them electronically with students (n=96)

- Having students prepare their own braille materials as someone read aloud to them information that was not accessible (n=61)

It was clear from the comments of the TVIs that some of their students had access to braille materials while other students did not. TVIs were also often unable to provide hard copy braille to their students because they did not have access to an embosser and/or braille translation software, were not allowed to take materials to students’ homes, or their students lived at a distance from them.

Braille provision and instruction in other tactile methods of learning, like abacus, has been quite challenging. My students using braille are averse to braille displays and strongly prefer paper braille. —No ethnicity or gender provided, Dually certified professional

Recommendations

Teachers of students with visual impairments serve a wide range of students both in age and ability. Most work as itinerant teachers going from school to school and often from district to district. In their role as TVIs, they are responsible for conducting assessments, two of which are specific to their professional role, the functional vision assessment and the learning media assessment. They are responsible for developing IFSPs for children under 3 years of age and IEPs or 504 plans for all other children on their caseloads. Supporting students in their general or special education classes is a cornerstone of their responsibilities, requiring them to produce materials, make accommodations, and teach skills in the ECC. To do their job effectively, TVIs need access to resources that enable them to support their students’ learning. The quick shift in how education is being delivered during the COVID-19 pandemic has caused challenges for TVIs. Administrators and policymakers can work with TVIs to develop strategies that will promote the success of students with visual impairments including those with additional disabilities and deafblindness.

Supporting Families

- Many families have had to make difficult decisions due to COVID-19. These range from deciding if they can take time away from work to meet with educational team members, whether their child should attend general education classes online when the materials are not accessible and their child is frustrated, or whether the discontinuation of educational services or therapies can be remedied through contacting administration and explaining their child’s needs.

- TVIs should acknowledge the realities of current and diverse home life situations. They must set appropriate but realistic expectations and goals for families and students that meet families where they are.

- Many families benefit from meeting other families whose children also have visual impairments and/or additional disabilities or deafblindness. During the unique situation COVID-19 has created, many families feel unsure and alone. TVIs can facilitate the introduction of families so they can support each other and share resources.

- Most family members are not familiar with the assistive or augmentative technology their child uses at school. They need instruction, support when there are problems, and suggestions on how to encourage their child in using the technology in the home and/or in the online environment.

Maintaining One’s Health and Professional Skills

- TVIs are dedicated professionals who were working hard and spread thin prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important that they and others are permitted time and opportunities for self-care. This may include ensuring that TVIs and all educators/ service providers get enough sleep, monitoring their mental health, and ensuring they obtain necessary healthcare.

- There are many ways for professionals to share and learn from each other. Websites, such as Paths to Literacy 22, collaborative and informative gatherings, such as the weekly TSBVI Outreach Coffee Hour 23, and additional professional development opportunities are important and vital resources that are continually needed in the profession.

Having Resources and Tools to Provide Accessible Instruction

- Students with visual impairments who are braille readers must have access to both hard copy (paper) braille and electronic braille. This often necessitates that someone prepare the braille materials (e.g., a braille transcriber, paraprofessional). Those preparing braille must have the tools they need to do so efficiently.

- Without accessible technology, curricula, and learning materials, students with visual impairments will not be able to progress in their learning. It is imperative that students, professionals, and family members have accessible materials in all facets of instruction.

- Many students are experiencing social isolation as a result of COVID-19. TVIs can bring students together online or over the telephone. Planning times when students can engage with others is important for their mental health. Professionals must provide a free, private, safe, and accessible venue for such meetings.

Considerations for Administrators

- Recognizing that some students may not meet all their IEP goals in the 2020–2021 school year and/or TVIs may not be able to deliver all the hours of service, administrators should plan for services to be delivered to students during the summer through Extended School Year (ESY).

- If administrators become aware that there are students or professionals whose tools and materials are in a locked school building or office, they need to provide access to the building so those tools and materials can be retrieved and used.

- Administrators must allow for TVIs to arrange for students to get materials, such as hard copy braille needed to access a class or a communication book developed for the student. Not all TVIs will have the time, willingness, and/or transportation to deliver materials to a student’s home. Options need to be provided to families and professionals such as allowing families to pick up materials from a centralized location, delivering materials via school bus, or mailing of materials.

- Administrators must ensure all members of the educational team are available to students during the time when instruction is not occurring in brick and mortar buildings. This includes the braille transcribers, for example, who prepare braille materials for students, or intervenors who support deafblind students by facilitating their communication and assist them in understanding what is happening around them.

- Administrators should allow time for educational team members, including family members and the student when appropriate, to meet to problem-solve, plan, and develop strategies so the student can fully participate in all areas of instruction. During meetings, team members can clearly delineate needed responsibilities and the individual(s) who are tasked with carrying them out.

- To ensure that all IFSP and IEP goals are monitored and progress documented, administrators must work with TVIs and other educational team members to set up realistic, simple, accessible methods to document student progress. They must ensure their staff do not place an unnecessary burden on families and students.

- Students who typically have one-on-one assistance during the school day generally are not going to be able to attend online classes without some level of family support. In some instances, this is not possible as family members have work or childcare responsibilities. Administrators, TVIs, and other educational team members must work together to develop creative solutions in these situations.

- Administrators must make digital accessibility a priority. Instructional technology, learning platforms, and materials must be accessible to students with visual impairments as well as the rest of the student population with and without disabilities. Nonvisual accessibility should be a priority. Additionally, administrators should provide general education teachers with training on accessibility, such as how to create accessible videos in order to deliver services to students and their families more appropriately.

- Administrators should work with TVIs and other educational team members to ensure that professional development opportunities are available and appropriate to new teaching practices, including online and hybrid instruction.

- Administrators and TVIs must work together to develop guidance on how evaluations and assessments, including the functional vision assessment and the learning media assessment, should be completed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Yue-Ting Siu of San Francisco State University and colleagues have developed the document Comprehensive Evaluation of Blind and Low Vision Students During COVID-19: A Guidance Document24 that can serve as a blueprint for other groups.

Considerations for Policymakers

- Policymakers must ensure that students with visual impairments are not forced to leave school at the end of the 2020–2021 school year because of their age without receiving the services they are entitled to on their IEPs. If goals have not been met and/or service time has not been provided, students should be able to receive ESY services or continue into the 2021–2022 school year if the educational team determines this is in the student’s best interests. The same considerations will need to occur as the end of the 2020–2021 school year approaches.

- In evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on the education of students with significant disabilities or deafblindness, policymakers should allocate additional funding and service time to address any regression in skills students have experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Assistive and augmentative technology provided at school must be available to students at home. Policymakers must ensure that funding and policies are in place to provide students with the necessary tools they need in order to access and participate in their education.

- It is not reasonable to expect every student, family, and professional to have Internet access that allows them to fully participate in all aspects of education. Funding and availability of Internet is essential in our education system. Policymakers must allocate sufficient funding to ensure all students can access online education and resources.

- There will be some professionals who are unable to maintain their caseload for many reasons including personal choice to leave their job as a TVI, health concerns for themselves or a family member, or lack of support from administration. Policymakers must have a plan in place to ensure qualified individuals are available who can step in and maintain the students’ educational program.

20. Chen, D., & Dote-Kwan, J. (2018). Promoting emergent literacy skills in toddlers with visual impairments. *Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 112*(5), 542–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1811200512

21. Penava, V., Bilic´ Prcic´, A., & Ilic´ic´, L. (2017). The influence of braille literacy programme length on frequency of braille usage. *Hrvatska Revija Za Rehabilitacijska Istraživanja, 53* (Supplement), 152–162.

22. http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/

23. http://www.tsbvi.edu/coffeehour

24. https://docs.google.com/document/u/1/d/1lZsOFKIJrLcHKRzVQVSkPRPII26iezV-fcfvQZQRlKc/copy