Chapter 8: Language of the Fingers

Like so many of the inventions that have been blessings to mankind, it came about accidentally. Opening up the world of written language to the blind was the furthest thing from the mind of the man who devised the basic concept that made it possible. He was Charles Barbier, an officer in Napoleon's army, and he was after a method of sending coded military messages that could be employed under cover of darkness. He called it écriture nocturne—night writing—a system of raised dots the fingers could interpret without the need for a betraying light.

The military value of Barbier's system was that these dots were not tracings of the ordinary alphabet. They were arranged into a secret code, based on a twelve-dot unit or "cell"—two dots wide by six dots high. Each dot or combination of dots within this cell arrangement stood for a letter or a phonetic sound.

Theoretically, Barbier's system was a breakthrough; in practice, it failed to work. It was too complex, too clumsy, too spread out. It did not take into account the limited area the human fingertip could span with a single touch.

In 1808, when écriture nocturne was presented to the French Academy of Sciences, it was rightly acclaimed as a brilliant invention. In succeeding years, Barbier experimented with variations of his system, employing different numbers of dots and different cipher codes. These were duly submitted to the Academy, and their published reports were widely circulated. Eventually, one such report found its way to the National Institution for the Blind in Paris where the twelve-dot system was tested and rejected as impracticable. But—and it is a large but—it was there that a thoughtful and creative member of the student body perceived that dot writing did have possibilities. The student was Louis Braille, who was only eleven years old and newly enrolled at the school when Barbier's invention was tried out there in 1820. Nine years later, Braille achieved his own breakthrough by finding a way to overcome the two fundamental flaws in Barbier's system. First he cut the number of dots in half so that a fingertip could encompass the entire cell unit of six dots in one impression. He then devised a new code, alphabetic rather than phonetic, employing combinations of these six dots.

The genius of Louis Braille's system was its simplicity. He arranged his dot cell into two parallel columns, three dots high. Starting with the letter a, he used the single dot in the cell's upper left-hand corner. For the next letter, b, he added the dot directly underneath. To denote the letter c he used the a dot and its corresponding dot in the upper right-hand corner. For identification purposes in teaching the system, he numbered his dots:

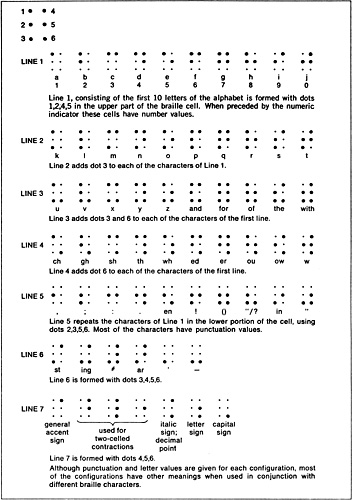

1 • • 4

2 • • 5

3 • • 6

The first ten letters of the alphabet, from a through j, employed only the dots in the upper two rows of the cell. Braille then made the next ten letters by adding the bottom left-hand corner dot, #3, to each of his first ten letters. Now he needed five more combinations (the French alphabet, which at that time omitted the letter w, had only 25 letters). For this purpose he used the lower right-hand dot, #6, adding it to his previous combinations. The accompanying diagram illustrates these principles.

Diagrams of braille cells, showing the construction of the braille code.

Because Braille's code was arbitrary, his symbols were capable of standing for anything that followed an accepted sequence: not only the letters of the alphabet but numerals, musical notes, chemical tables, etc. All the reader had to know was which code was being used. For the numerals 1 through 9, for example, Braille's code used the same symbols as the first nine letters of the alphabet. The tenth letter stood for zero. When numbers appeared in the context of a reading passage, a coded signal alerted the reader to the fact that the next cell represented a numeral and not a letter. This coded signal, called the numerical indicator, is identified as # in Line 6 of the diagram.

Since six dots could be arranged into 63 different patterns and the alphabet required less than half of these, there was room within Braille's code for this numerical signal and a good many others to represent diphthongs, conjunctions such as with or and or for, common letter combinations such as ch or th, and other useful adjuncts to written language.

The braille code shown in the diagram is the modern version, but in most essential respects it is unchanged from the alphabetic code Louis Braille published in 1834. Five years earlier he had worked out and published his code to music notation; this, too, has remained basically unchanged.

Louis Braille was not the first to realize that fingers were to the blind what eyes were to the sighted, but he was the first to work out a practical method of employing the fingers to do the work of the eyes. Official recognition of his genius came only after his death, but within his lifetime he had the satisfaction of knowing that his students at the school for the blind in Paris could learn and use and profit from the key he had fashioned.

Born January 4, 1809, in the village of Coupvray, not far from Paris, Louis was the son of a harness maker. While playing with one of his father's tools, a sharp knife, the three-year-old child accidentally slit one of his eyes. The resulting infection also destroyed the vision of the other eye; a bright little boy was now totally blind.

For some years Louis attended the village school with his brothers and sisters, but in 1819 his father brought him to Paris and the National Institution for the Blind. Here he remained, first as a student and then as an instructor, and it was here that he adapted the Barbier system to the needs of blind persons everywhere. His health was frail, however; whether due to tuberculosis or some other respiratory ailment, he coughed so incessantly that it became increasingly difficult for him to lecture. Eventually, he had to give up and return to Coupvray. There he died on January 16, 1852, two weeks after his forty-third birthday. He was buried in the family plot in the village cemetery until, on the centennial of his death, his body was exhumed and ceremoniously transferred to the Pantheon in Paris. In deference to Coupvray, which had erected a monument to Braille in its main square, the skeleton of his right hand—"the hand with the reading fingers"—was left to repose forever in its native earth.

A major virtue of Barbier's system, which Louis Braille recognized and retained, was that it could be written as well as read without benefit of sight. Barbier had invented a writing frame, consisting of a board and a stylus, which Braille adapted. The governing principle of this device remains in effect today in the form of the modern braille slate. This consists of two metal or plastic plates, hinged together at one end and open at the other to permit a sheet of paper to be inserted between them. The upper plate is pierced by little windows, each the exact size of a braille cell. Directly under each window, on the lower plate, are six shallow pits arranged in the braille cell pattern: two pits wide by three pits high. Embossing takes place when the stylus is placed in a window and is pressed downward against the paper in order to form each braille character, dot by dot, against the corresponding pit of the lower plate.

To read what has been embossed, the paper must be turned over so that the dots protrude upward. Turning the paper transposes left and right, as in a mirror image. Therefore, writing by means of a braille slate is done backwards, from right to left instead of vice versa, so that the letters, when the paper is turned, will read in the customary left-to-right order. Confusing as it may sound, this practice soon becomes quite automatic for the blind user of braille.

It was the fact that blind people could write it as well as read it that gave braille a commanding advantage over other early methods of embossed writing. These were tried, in varied forms, for many years both before and after the braille code made its appearance.

Most of the other efforts to produce tangible type—letters cut out of wooden blocks or cardboard, letters carved in relief on wood or incised into wood or wax—suffered from a common error of logic. They simulated the linear alphabet of the sighted and thus, as the blind French philosopher Pierre Villey put it, made the mistake of "talking to the fingers the language of the eye." Specifically designed for tactile use, the braille code could not be easily read by the eye. This was one reason why, despite its instant appeal to blind students, braille encountered considerable initial resistance from sighted teachers. Obviously, it was easier for such teachers to supervise and correct a student's work if they could follow visually what the student was writing tactually. There may well have been another reason too; braille could be taught by blind teachers, and this constituted a threat to the job security of the sighted.

In the English language, various forms of tangible type in linear form were developed in England and Scotland during the nineteenth century. Only one of these survived. Moon type, named after its originator, Dr. William Moon, consisted of stripped-down and simplified versions of roman capital letters. The letter A, for example, appeared without its crossbar; the letter D, without its front vertical line. Moon type was first produced in England in 1847 and was introduced in the United States in 1880. As will be seen in a later chapter, it proved particularly useful as a reading method for persons blinded late in life who felt unequal to mastering braille.

Early American efforts at production of literature for finger-readers were also in linear type. The most enduring of these was Boston Line Type, an angular modification of roman letters in both upper and lower case. It was devised by Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, founder of the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts. The first book printed in Boston Line Type was Acts of the Apostles, which Perkins produced in 1835. This was soon followed by editions of the New Testament and the Old Testament.

Of greater importance than the Scriptures in the education of children were the textbooks that were printed for the students at Perkins and adopted by many of the other schools for the blind that were then rapidly emerging in other parts of the United States. Boston Line Type, which thus became the predominant print medium for the blind in the United States for four or five decades, served for secular literature as well.

Among the books printed in this form was The Old Curiosity Shop; it makes an intriguing footnote to history that the $1,700 cost of this embossed edition was defrayed by Charles Dickens himself. Dickens had visited the Perkins school in 1842, during his first trip to the United States, and had been so impressed by what he saw there that he devoted 14 pages of American Notes to a description of the school, and particularly to an account of Dr. Howe's pioneering accomplishment in educating a deaf-blind girl, Laura Bridgman. Some forty years later, it was this passage that kindled in Helen Keller's mother the hope that her own little deaf-blind daughter might also be given a chance in life. With the help of Alexander Graham Bell, the Kellers approached the then director of Perkins, Michael Anagnos, to ask whether the school could furnish a teacher familiar with the methods that had brought enlightenment to Laura Bridgman. Anagnos, who was Howe's son-in-law, chose one of the brightest of his recent graduates, young Anne Sullivan. Thus was forged the chain of coincidence that brought together the twosome, Helen and her teacher, whom Mark Twain called the Miracle and the Miracle Worker.

By the time Anne Sullivan became a student at Perkins in the early 1880s, the dot system was already in use in most American schools for the blind. Soon after braille's official adoption in Paris in 1854, Dr. Simon Pollak, one of the founders of the Missouri School for the Blind, was traveling in Europe. He learned about braille and brought the new code back with him. Some of the school's faculty offered the usual objections of the sighted to this alien style of finger-reading, but the students seized upon it with delight. It was said that they used braille to pass surreptitious notes—sometimes love letters—to one another, knowing that the messages, if intercepted, could not be read by their teachers. The school's music teacher was the first to yield; soon thereafter the rest of the faculty followed and instruction in literary braille was begun.

As the dot system gradually began to prevail over linear types in Missouri and elsewhere, various educators of the blind started trying to improve the braille code. These well-intentioned efforts led to unfortunate results, for it was the simultaneous existence of differing code systems that ultimately precipitated the "war of the dots" that raged over so many decades.

To a lesser degree, somewhat the same sort of chaos arose in England, but the British resolved their differences with greater speed and firmness. By 1905, British braille had been systematized and a uniform code adopted and divided into two levels. Grade 1 was basic braille, in which each word was spelled out, letter by letter. Grade 2 introduced 197 space-saving contractions or abbreviations for frequently used words. In the United States, it took an additional dozen years and a great deal more controversy before agreement was reached on the uniform type system known as Revised Braille Grade 1½. This was essentially the same as British braille, except that it rested partway between the two British grades, employing only 44 of the Grade 2 contractions. This half-step, which was officially adopted by American schools and agencies for the blind in 1917, left enough of a gap between the two English-language systems to hinder free exchange of literature across the Atlantic Ocean.

To close that gap and establish a uniform braille code was one of Robert Irwin's objectives during the early years of the American Foundation for the Blind. His confidence was bolstered by a favorable omen. In the mid-Twenties, negotiations were begun aimed at achieving international agreement on a universal braille code of musical notation. This was an important need. Music was a major vocational outlet for blind people, and one in which gifted blind singers, pianists, organists, and violinists the world over achieved professional renown. The study of music traditionally occupied a prominent place in the curriculum of every school for blind children. Many of the graduates earned their living as performers, music teachers, or piano tuners. Music scores for the sighted used an internationally recognized set of symbols; why should this not be so for the blind? But several styles of music notation in braille had been evolved, and until there was agreement on a single style, a blind musician in London could not readily make use of a braille score produced in Philadelphia or Vienna or Rome.

A five-nation conference held in Paris in the spring of 1929 reached agreement on an international music code for the blind; thirteen other nations had agreed in advance to accept the conference decisions. "The world is at last in accordance in the usage of braille musical symbols," the Outlook for the Blind reported joyfully in its account of the conference. "We may congratulate ourselves on sharing in the final triumph of the braille system."

The man who represented the United States in this triumph was Louis W. Rodenberg, who was in charge of braille printing at the Illinois School for the Blind (now the Illinois Braille and Sight Saving School). The Illinois institution, a pioneer in the development of mechanical aids for braille production, had long been a leader in the printing of musical scores. Rodenberg, who became associated with the school in 1912, had worked out a key to braille music notation which brought him a national reputation when it was published in 1917. In 1924 the Foundation commissioned him to expand his earlier work into an encyclopedia of braille music notation; it was issued the following year.

Rodenberg had evolved a particular style, known as "bar over bar," for the arrangement of braille music. He had also experimented with various ways to publish songs that would enable blind singers to learn words and music simultaneously. The year after the Paris conference he achieved a long-cherished dream when he began editing the American edition of Musical Review for the Blind, the country's first professional music journal in braille. His pioneering achievements in brailled music were honored in 1943 when he was awarded the Foundation's Migel Medal. Rodenberg retired from the Illinois school in 1963 and died three years later at the age of seventy-four. He lived long enough to see established in the Library of Congress a comprehensive collection of brailled musical scores, texts, and instructional materials to be made available for nationwide use under a federal bill enacted in 1962.

It may seem odd that Robert Irwin, who regarded books for the blind as a top priority, encouraged progress on a music code before tackling the knottier question of achieving uniformity of braille literature in the English-speaking world. He had his reasons. For one thing, he was working on improving the mechanical aspects of braille production so as to reduce costs. For another, as he was to point out in his posthumously published reminiscences, As I Saw It, both the American readers of braille and the printing houses that produced it were thoroughly tired of changes. The printers had had to scrap thousands upon thousands of costly printing plates in earlier versions of braille after Grade 1½ was adopted; they were understandably reluctant to undergo the same wasteful expense should Grade 1½ have to be modified or abandoned by virtue of an agreement with the British. As for blind readers, wrote Irwin:

Many still living had first learned [Boston] linetype, then New York Point, then American braille, then Revised braille grade 1½. The rank and file of finger readers had a good deal of sympathy with a speaker at one of the national conventions who in a burst of oratory said, "If anyone invents a new system of printing for the blind, shoot him on the spot."

The right psychological moment for change drew nearer as plans were developed for the convening of a world conference of the blind in New York in 1931. In an atmosphere of international cooperation, and with the way already paved by the agreement on braille music, the climate might prove opportune for a final accommodation with Great Britain. To win over those still reluctant, Irwin added a dollars-and-cents inducement by having a staff assistant, Ruth E. Wilcox, conduct a statistical "contraction study" to determine the relative amounts of space (and thus, of expense) required by the British and American grades. The study demonstrated that Grade 2 occupied from 12 to 14 percent less space than Grade 1½. For example, the six-letter word nation in Grade 2, using an n followed by the two-cell contraction for ation, needed only three braille characters, whereas the same word written in Grade 1½ contained all six letters and therefore required six braille cells.

On his way to a meeting in Vienna in the summer of 1929, Irwin stopped off in London and found the British more receptive than in the past. He wrote Migel about his discussions: "I really believe that, if we put sufficient drive behind this thing, we can bring about almost complete uniformity." His optimism was justified when Sir Ian Fraser (later Lord Fraser of Lonsdale), chairman of St. Dunstan's Executive Council and an acknowledged leader of the British blind, told the opening session of the World Conference on Work for the Blind in 1931: "It is my belief that a little common sense and a little give and take on both sides of the Atlantic may bring about a uniform type. … "

The give and take duly took place; in September 1932 the Outlook triumphantly headlined an article: "Uniform Braille for the English-Speaking World Achieved." The compromise version, named Standard English braille, was immediately adopted for all adult literature. For some years, schoolbooks for beginning readers retained the easier Grade 1½, but this was gradually abandoned and all books came to be produced in Standard English braille.

This does not mean, however, that the braille codes remain static. Because braille communicates a living language, it needs ongoing surveillance and periodic updating to reflect the new words, concepts and processes of a scientific and technological age. To insure consistency of treatment by braille printing houses, a group known as the American Braille Commission was organized soon after the agreement with the British. This was superseded in 1950 by a larger group, the Joint Uniform Braille Committee of the AAIB and AAWB, which gave way, eight years later, to a more permanent jointly sponsored body, the Braille Authority.

In 1968 a National Advisory Council to the Braille Authority was formed. It consisted of educators and service program leaders, the objective being to establish closer liaison between the producers and the users of braille materials. The Braille Authority and its advisory body concern themselves with such problems as improved methods of embossing maps, diagrams, charts and tabular material, the development of advanced computer symbol transcriptions and of notation systems for higher mathematics, the introduction of a music code specifically adapted for the percussion and plucked instruments popularized by rock and country music, and comparable changes designed to enable braille readers to be part of the modern world.

When the Foundation asserted in a 1924 report that "no more valuable contribution could be made just now than to discover ways of reducing the cost" of braille literature, it did not have in mind merely economies that could be effected through greater use of contractions. American methods of printing literature for finger-readers were inefficient and far behind European methods. To understand the steps initiated to remedy these flaws, it is necessary to go back in time to review the progress made in dot-writing after the development of the braille slate.

A sheet of embossed dots produced by means of a braille slate is just that: a single sheet. To obtain more than one copy requires duplicating machinery of some sort. Early efforts to accomplish this were adaptations of standard inkprint production methods. Movable type set up the dot pattern in high relief. This was then locked into a frame, placed in a flat press, and applied to heavy paper with sufficient pressure to make dents in the paper without piercing it. Sometimes the movable type was cast into metal bars before being put on the press. Another method was to punch dots in a metal plate by means of a heavy stylus and a hammer. The hand-punched plate then served as a stereotype whose dots could be transferred to paper with the use of a flat or rotary printing press. Since all of these methods involved hand composition, they were necessarily slow. There was yet another time factor: once the heavy braille sheets were embossed, they had to be varnished and dried to preserve the raised dots.

When the first commercial typewriter was successfully marketed toward the end of the nineteenth century, its operating principle offered a way of achieving much greater speed in brailling. In 1890 Frank H. Hall was appointed superintendent of the Illinois Institution for the Education of the Blind. The forty-nine-year-old Hall, who had had twenty-five years of teaching and supervisory experience in public schools, was appalled to discover what primitive educational tools were available to his blind students. It occurred to him that the typewriter principle could be made applicable to the production of dot-writing. Only six keys would be needed, one for each dot in the braille cell. With fingers on the keyboard, a blind person could strike the combination of keys needed to produce a braille character embossed on the paper in the machine's roller. It would be a little like playing a chord on the piano. The carriage would then move the paper along to where the next braille cell would be made, while word separation could be achieved with a space bar.

With the help of G.A. Sieber, a skilled machinist, Hall completed his work on the braille version of the typewriter in less than two years. Exhibited at the 1892 convention of the American Association of Instructors of the Blind, his invention was received with acclaim. Those who saw Hall's daughter give a demonstration on the machine at a speed of 100 words a minute "were almost dumbfounded with surprise and delight," according to one eyewitness.

Hall's machine, called a braillewriter, was a significant factor in giving braille a commanding edge over its principal competitor, New York Point. The latter was also a dot system. It had been devised in 1868 by William B. Wait, superintendent of the New York Institution for the Blind (later named the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind), as an improvement over Louis Braille's code and, because of certain desirable features, it was popular with many educators.

New York Point differed from braille in two essential respects. Whereas Louis Braille had developed his code in what appeared to him to be a logical sequence, starting with a single dot for a and gradually increasing the number of dots as the end of the alphabet neared, Wait thought it more scientific to take into account the frequency of occurrence of the various letters. The letter t, for example, occurs much more often in the English language than the letter k. In braille only two dots are needed to make k, which is the 11th letter of the alphabet, whereas t, the 20th letter, requires four dots. Wait changed all that by assigning the fewest dots to the most frequently used letters.

The other difference was that whereas braille had as its unvarying base a cell two dots wide by three dots high, the New York Point cell was only two dots high, but the width of its base could be one, two, three or four dots, depending on the number needed to denote a particular letter.

That New York Point was a good and sensible system was undeniable. Why, then, did it fail to win out over braille? Over-promotion may have been one important factor. Wait was a brilliant man but so hard-driving and zealous that he antagonized many in influential quarters. Opposition spurred him on to ever more militant measures, which ultimately cost him the loyalty of even those who shared his high opinion of New York Point. It became a vicious, inflammatory spiral. To review the detailed records of the "war of the dots" is to uncover the stuff of melodrama, a sorry tale that victimized the very people the battling adversaries were trying to help.

Frank Hall was a conscientious educator. Once given charge of a school for blind children, he lost no time in making a thorough study of the relative merits of braille and New York Point. There was a powerful practical argument to sway him in favor of the latter; in 1890, virtually all the schoolbooks for blind children produced under federal subsidy by the American Printing House for the Blind were in New York Point. Hall's school had access to free books if its students were instructed in Wait's system. Textbooks in a form of braille developed at the Perkins school in Boston and known as American braille were being produced by the Howe Memorial Press, a Perkins affiliate, but these were not federally subsidized and had to be paid for. The Illinois institution, like most other schools for the blind, had a small printing shop of its own and produced much of its educational material in that way.

What, then, decided Frank Hall in favor of a machine that would write braille rather than New York Point?

At first I thought of making [a machine] to write New York Point, but when I took into consideration that the letters of that system were not of uniform length, [while] each braille character occupied precisely the same amount of [horizontal] space as any other character, I determined to attempt the easier task. … When they made the first typewriter ever made, the first thing they had to do was to make the letters of uniform length. The i in the Remington occupies exactly the same space as the m. … It seemed to me that was the only proper system on which to attempt to make a machine to write for the blind.

It did not take long before Wait developed a comparable writing machine called the Kleidograph to handle New York Point. But the Hall braillewriter had the inside track and its existence had already precipitated a significant change in the production of educational materials for blind children. As additional school superintendents saw the potential of the braillewriter, they switched from New York Point and successfully demanded that the American Printing House use part of its federal grant to manufacture textbooks in braille as well as in New York Point.

Once there existed a machine that could punch braille dots on paper, the logical next step was to make it strong enough to punch through metal and produce a stereotype from which copies could be duplicated. A year later this had been accomplished. Hall also devised a method of motorizing the machine. "The work is done by the electric motor," he explained, "and all the fingers have to do is to select the keys and they do it almost as fast as you can play a piano."

Hall made these remarks during one of the crucial battles in the war of the dots. This was the series of hearings held in 1909 by the New York City Board of Education to decide whether braille or New York Point should be the medium of instruction in the day school classes for blind children the city was about to institute. The defeat of New York Point in the city of its birth was a crushing blow to the aging William Wait. He died in 1916, and was thus spared the pain of seeing his brainchild receive the coup de grâce the following year, when agreement was reached to print all future literature for the blind in braille Grade 1½.

By that time, Hall was also gone. He had left the Illinois school in 1903 and worked in the field of agricultural education until his death in 1911. He never patented his machines, refusing any personal profit from their invention. His attitude was squarely in the tradition, unbroken to this day, that equipment for the use of blind persons was to be sold at cost.

Because of the diversion of energies resulting from the battle over types, little progress was made in American braille production methods during the thirty years following the invention of Hall's braillewriter and stereotyper. One of the earliest steps taken by the Foundation was to call a conference of the leading braille printers and some of their major customers for a pooling of ideas on how to make braille books better, cheaper, and less bulky. Their principal recommendations were that the size of braille books be standardized, and that books be printed on both sides of the page.

Two-sided book printing, which had long been standard practice in Europe, had never successfully evolved in the United States. To study European methods, a three-man committee consisting of Robert Irwin, E.E. Bramlette (superintendent of the American Printing House for the Blind), and Frank C. Bryan (manager of the Howe Memorial Press) visited braille printing plants in Great Britain, France, Germany, and Austria during the summer of 1924. The committee concluded that it would take six months to a year to adapt American production methods to the more efficient and economical systems used abroad, and they recommended that some experimentation be undertaken before any of the expensive European equipment was imported.

The committee's time estimate proved optimistic; it was to take a lot longer than a year, a great deal of costly engineering, and a wholly unanticipated series of setbacks before two-sided book printing became standard practice in the United States.

The process involved in printing braille on both sides of the same sheet was called interpointing. It required a precise placement of plates and paper, so that the dots embossed on one side would fall between the lines of the dots embossed on the other so that fingers reading one side of the sheet would not be confused by the dots on the reverse side.

That interpointing was possible with American equipment had already been shown. The Ziegler Magazine shop had adapted its Hall stereotyper to produce two-sided printing some years earlier. Results were far from perfect, but the magazine's readers were so happy to get twice as much reading matter in the same number of pages that they got used to the imperfections. However, while relatively crude work might get by in something as ephemeral as a monthly magazine, a much higher quality of production was needed in books designed to be circulated and read by many over a period of years.

The dominant producer of printed matter for blind readers was then, as it had been for many decades, the American Printing House for the Blind in Louisville, Kentucky. This unique organization, originally an offspring of the Kentucky School for the Blind, was founded in 1858 by action of the Kentucky Legislature. It became an official printer of schoolbooks for the United States in 1879, when Congress passed "An Act to Promote the Education of the Blind."

Under this act, a perpetual trust fund of $250,000 was set up, to be invested in United States interest-bearing bonds, the income from which, at 4 percent, would go to the Printing House on condition that the $10,000 annual yield be spent on the manufacture of books and tangible apparatus to be distributed, free of charge, to tax-supported residential schools for the blind. Distribution was to be on a pro rata basis, in proportion to the schools' enrollment of pupils. A further provision was that the superintendents of these schools were to serve as ex-officio trustees of the Printing House. (In 1961, five years after the act had been amended to make Printing House services available to visually handicapped children attending regular public day schools as well as those enrolled in special schools and classes for the blind, a further amendment enlarged the ex-officio trusteeship category to include representatives of state education departments.)

In 1906 the bond feature was eliminated in favor of a direct federal grant of $10,000 to be made annually in perpetuity. In 1919, an additional annual grant of $40,000 was voted, reflecting the nation's population growth and consequent increase in the number of children attending schools and classes for the blind. As the latter continued to grow, so did the Printing House grant. It was upped to $75,000 in 1927, to $125,000 ten years later, to $260,000 in 1951, then to $410,000 in 1956. In 1962, the ceiling on appropriations was lifted, and the Printing House was charged with seeking each year's budget on the basis of proven needs. Its scope of service was enlarged in 1970 when parochial and private schools were permitted to participate along with the tax-supported residential and day schools in free receipt of educational materials for their blind pupils.

In the fiscal year ending June 30, 1972, the federal grant to the Printing House amounted to $1,590,000. This sum, known as the quota fund, supplied 21,846 pupils in schools and classes for the blind with educational materials in the form of books in braille, large type, or sound recording, as well as maps, globes, slates, music scores and equipment, and a wide range of other educational aids and apparatus.

The overall operations of the American Printing House now encompass far more than the materials produced under the federal grant. To supplement their quota allotments, schools purchase additional supplies and equipment that are sold on a non-profit basis. The Printing House also handles contracts from government bureaus, voluntary and business organizations for the manufacture of various kinds of books, periodicals and tangible aids for the blind. Outside of its federal grant, therefore, the Printing House functions as a non-profit organization, part of whose funds come through contributions from the public. With a full-time staff of 550 and an overall business volume which in 1972 exceeded $7,500,000, it remains the world's largest publishing house for the blind.

In the early Twenties, virtually all the other braille printeries in the United States were offshoots of schools for the blind. There were a dozen or so all told, only two of which—the Howe Memorial Press in Boston and the Clovernook Printing House for the Blind in Cincinnati—were large enough to handle more than local work. (The endowed Matilda Ziegler Magazine for the Blind was bigger than either, but it was in a class by itself.) Like the American Printing House, all these smaller braille presses were long-established and settled in their ways.

At the point where the Foundation decided to take forthright action to modernize braille publishing practices, a fresh wind began to blow in from the west in the person of J. Robert Atkinson of Los Angeles. Atkinson, who had founded the independent Universal Braille Press in 1919, was a blind man endowed with an abundance of ability, ambition, and aggression. Over the next two decades he was to administer several salutary shocks to sting the established printing houses out of lethargic complacency. His actions were also to give rise to bitter personal rivalries, passionate partisanships, and unruly public controversies that proved deeply disturbing to blind people throughout the nation.

A publicity release issued by Atkinson's organization in 1944 began: "J. Robert Atkinson lost his sight in an accident in 1912 when working as a cowboy in Montana." Atkinson almost never bothered to contradict the impression that this accident had taken place out on the open range. Even the obituary put out by his organization when he died in 1964 stated, "Bob Atkinson was blinded by backfire from a revolver while working on his brother's cattle range in Montana." In actual fact, however, according to an authorized biography published toward the end of Atkinson's life, the accident took place in a Los Angeles hotel room.

Atkinson's tendency to evade inconvenient truths was one of the traits that made him a storm center in work for the blind. On the other side of the ledger was his admirable degree of grit. Following the accident that cost him his sight, he refused to be overwhelmed by blindness and proceeded to teach himself all forms of finger-reading. Simultaneously, he developed an interest in Christian Science and obtained permission from that church's headquarters in Boston to hand-transcribe the works of Mary Baker Eddy into braille for his private use. This undertaking had two results. He began to think about braille production, and once he had established himself in business as a braille printer, the Christian Science Church became one of his principal customers.

In 1919 Atkinson set up the Universal Braille Press in the garage of his home in Los Angeles. With the financial help of a philanthropic couple whose interest he had attracted, he began in business by printing the King James version of the Bible in the newly approved Grade 1½ braille. This was a five-year project, in the course of which he began experimenting with improvements in braille printing methods.

The initial bylaws of the American Foundation for the Blind stipulated, as one of the ten categories of special interest groups to be given places on the board of trustees, "technical heads of embossing plants and departments." At the Vinton convention, where these bylaws were adopted, Atkinson, though not present and a newcomer to the field, was named to represent the embossers category. He attended the first meeting of the Foundation trustees, which was held in New York in November 1921. On his return to California he submitted a bill for his travel expenses, with the explanation that the trip from the West Coast was too costly to be met out of his personal funds. He had to travel with his wife as a sighted escort, which meant two fares at that time. While this voucher was honored, the board was not in a financial position to go along with Atkinson's formal proposal that the expenses of trustees attending future meetings be routinely met. At the expiration of Atkinson's three-year term, the embossing plant delegates elected another representative to serve on the Foundation board.

In 1924 Atkinson announced the development of an improved braille stereotyper and wrote an article to which the Outlook for the Blind, in its first issue under Foundation auspices, gave considerable prominence. The Foundation had just sent three men abroad in search of improved printing methods. Naturally it was interested in examining the machine which Atkinson's article called "superior to any model on the market." In December 1924 the executive committee authorized a three-man committee to visit Los Angeles for the purpose of seeing the Atkinson stereotyper and its performance. Atkinson demurred on the grounds that the equipment was undergoing further refinement. But he did agree to bring the stereotyper to New York for a meeting of braille printers the following September, and the Foundation acceded to his request that it meet his travel costs.

At that meeting, two other stereotypers capable of being adapted to two-sided printing were also exhibited—one by Frank Bryan of the Howe Press in Boston, and the other by Joseph Brusca of the Ziegler Magazine plant in New York. In the course of the two-day session demonstrations were given and the machines carefully inspected. All three had merit, but none met the desired standard.

While encouraging further work on the three models (a $3,000 fund was raised to help meet the expense of mechanical modifications), the printers attending the conference reached the same conclusion as the delegation which had visited the European printing plants the previous year: a mechanical shop was needed in which experimentation could be carried out and new equipment and processes thoroughly tested for performance, ease of operation, reliability, and durability. They urged that the Foundation establish such a shop.

Inasmuch as the end product would be better, cheaper, and less bulky books for the blind, a logical source of financing was the Carnegie Corporation, whose major interest was library work. The Foundation turned to the American Library Association with a request that it use its influence to secure a Carnegie grant of $10,000 annually. This plan succeeded; in May of 1926 the Carnegie Corporation voted the Foundation $10,000 for 1927 on a matching basis.

In January of 1927 the Foundation's mechanical shop, forerunner of its engineering division, was born. It began with the utmost modesty in space rented in the Ziegler Magazine plant. Julius Hurliman, a Swiss mechanical engineer with extensive experience in the printing field, was put in charge. He and a helper constituted the entire staff. Hurliman was "an original fellow, a hard worker, and deeply interested in the humanitarian as well as the mechanical aspects of his job," according to Irwin, who made this statement in a letter to Dr. Frederick B. Keppel, president of the Carnegie Corporation, reporting the shop's progress six months after its opening. Two-sided printing was already under way in Atkinson's plant, he wrote, but the process was not yet reliable enough. However:

If our shop can have support sufficient to continue its operation we will within two or three years revolutionize the method of printing for the blind in this country. Four Braille publishing plants have already advised us that they will adopt two side printing just as soon as we can recommend satisfactory machines.

In this account of early experimental efforts, the American Printing House for the Blind has been conspicuously absent. Even though its superintendent, E.E. Bramlette, was a Foundation trustee and had been drawn into every step of the effort to improve braille production, the Printing House had assumed an attitude of studied indifference toward interpointing. In an attempt to elicit some action, Foundation president Migel wrote to the Printing House's president, John W. Barr, in June 1926, asking that the question of two-sided printing be put before the latter's trustees. The reply was a flat rebuff. The Printing House, Barr wrote, had concluded that

interpointing, while it saves about one-third of the paper, space and binding, costs about one-half more labor. This extra cost of labor much more than offsets the saving in material. [Furthermore, interpoint printing] could not apply to Primary and Intermediate text books for the schools and is of very doubtful use in the high school texts. Therefore, while interpointing may save space for the librarian and adult readers, it will undoubtedly be of little or no use to the schools for the blind.

There was only one weapon left that might prevail over intransigence, and the Foundation proceeded to use it. Its braille memorial fund campaign was under way and monies were being collected from various organizations to underwrite the brailling of adult books. Irwin directed the bulk of this business to the Universal Braille Press, and they agreed to produce the books in interpoint. With experience, prices came steadily downward, thus demolishing the Printing House's argument of higher labor costs. Although his equipment needed improvement, Atkinson's work was of high quality and he was eager to have the business. "The work we have received from the Foundation has undoubtedly helped us wonderfully and perhaps enabled us to survive," he wrote.

After a year or so of watching order after order go to California, the American Printing House for the Blind was aroused to the point of complaining publicly about the Foundation's failure to assign it the lion's share of the contract work. Its argument was that if all braille printing were concentrated in a single shop, there would be more efficient use of plant and lower costs that would benefit all blind readers, children and adults alike. Irwin thought just the opposite: "A little friendly competition is good for any large organization, little as the management may enjoy it."

In one way, the spur of competition had the desired effect. Reversing its stand, the Printing House decided that interpointing was practicable after all and began bidding aggressively on contracts for two-sided printing. In another way, however the effects were regrettable. With the support of a number of school superintendents, Bramlette mounted a vigorous campaign to swing public opinion in favor of centralizing all braille printing in Louisville. Atkinson, whose temper had a low flash point, reacted with understandable sharpness. In mid-1928 he wrote Bramlette accusing him of seeking a monopoly and alleging that the Printing House quoted prices below cost when bidding competitively but at the same time charged unreasonably high prices on non-competitive contracts.

Atkinson circulated copies of this letter far and wide. But he, too, was reluctant to face increased competition. He wrote Migel: "I do not think it wise for [the smaller braille plants] to become too ambitious, nor do I think it wise for other plants to be created." Here he was intimating an idea he was later to proclaim publicly: the Universal Braille Press in the West and the American Printing House for the Blind in the East should divide the country between them.

It is worth noting that at this stage Atkinson clearly regarded the Foundation as his ally. Bramlette thought so, too, and was sufficiently exercised over what he regarded as favoritism toward Atkinson to bring the matter up before the Foundation's executive committee. Yet not many months later Atkinson was to appear before a Congressional committee to denounce the "entangling alliance" between the Foundation and the Printing House, and although there was not in fact any such alliance, the Foundation was to speak up forcefully in defense of the Printing House against some of Atkinson's accusations. Then, only a year or two thereafter, the Printing House was to strive mightily to defeat a Foundation proposal which it regarded as threatening to its interests. Such was, is, and probably always will be the price of nonpartisanship.

Before any of this transpired, the Foundation itself was swept into the field of competitive fire. Rumors were rampant that its experimental shop was designed to become a braille publishing house. So widespread was this impression that it was deemed advisable, in early 1928, to address a circular letter to all organizations and professional leaders in work for the blind, specifically denying any such intention and reiterating that it was purely a "mechanical research laboratory."

The fact that the Foundation shop did produce a limited amount of embossed literature was due partly to the conditions of the Carnegie grant. Carnegie support, which was continued for 1928, was predicated on the Foundation's working with the American Library Association in "a reading course project for the blind, including experimentation in Braille printing." The literature produced consisted of a number of reading course pamphlets plus braille editions of a Foundation professional journal, the Teachers Forum. At a later point, the shop also printed the first braille editions of the Outlook for the Blind.

That the shop did indeed function as a mechanical research laboratory was soon demonstrated. The Cooper Engineering Company of Chicago announced its intention to discontinue manufacture of the Hall stereotyper, the Hall braillewriter, and other equipment for the blind it had been producing ever since the days of Frank H. Hall. For the Cooper firm, whose principal business was the manufacture of such heavy industrial equipment as oil well machinery and gas main couplings, the production of mechanical appliances for blind users constituted a small, unprofitable sideline. The Foundation agreed to buy the Cooper jigs, dies, and other production equipment; while it did not intend to become a manufacturer of appliances any more than it intended to become a braille publishing house, it felt sure that its shop could effect some greatly needed improvements, particularly in the braillewriter.

The end product of the Foundation's efforts to modernize braille production was that two-sided printing became standard practice. As for the Foundation's experimental printing shop, which remained in existence until the beginning of 1932, it chalked up three major accomplishments: the development of a functional stereotyper, the development of a new braillewriter, and the successful adaptation of a European method for duplicating hand-transcribed braille manuscripts.

Once the shop had perfected a stereotyper capable of consistently precise performance in producing interpoint work, the machine was submitted to the American Printing House for the Blind for testing under actual production conditions. Two other stereotypers, one of them Atkinson's, were simultaneously subjected to the same use test. The Printing House agreed to adopt, and to manufacture in its own facilities, whichever model it found to be best. The test results favored the Foundation's machine, so a contract was duly signed in February 1932 under which the Printing House would manufacture the stereotyper in the future while the Foundation would market it. In all, 16 of these machines were produced; 13 were sold in the United States for installation in four printing houses, four schools for the blind, and two large local service agencies. The remaining three were bought by braille printing houses in Canada, South America, and England.

(In the years following these pioneering efforts many of the advances achieved in general printing were adapted for use in braille publishing. Probably the most dramatic of these was an automated process, put into limited production at the American Printing House for the Blind in the Sixties. It employs a key punch computer program to translate inkprint text into braille characters which, by means of magnetic tape, then embossed directly onto metal stereograph plates. The key punch operator does not have to know braille; the coding is done by the computer. As of 1972, however, most braille manufacturing continues to use trained stereotypists who operate braillewriting machines to translate inkprint copy onto the metal plates. The reason is cost.)

Development of a greatly improved portable braillewriter was completed in the experimental shop at the beginning of 1932. The new machine was more precisely engineered, easier to maintain, more efficient in operation, and considerably quieter than the Hall braillewriter. When it came to commercial production, however, a serious dilemma arose. Because of a necessarily limited market, the unit cost of a braillewriter was far higher than blind people could afford to pay; no production run would be large enough to amortize the cost of tooling. Production plans were deferred for some months while the Foundation shopped for the lowest possible price. In 1933 a deal was worked out with the L.C. Smith & Corona Typewriter Company under which the Foundation agreed to pay $19,000 for the production dies and tools and to advance $12,500 in capital to finance the manufacture of each lot of 500 braillewriters. Marketing was handled by the Foundation, which sold the machines at manufacturing cost. The first machines of the initial lot of 500 came off the assembly line late that year. They were an instantaneous success.

The Howe Memorial Press in Boston, which had been manufacturing its own braillewriters since 1921, decided to discontinue them following the introduction of the Foundation's model. In announcing this decision at the 1933 convention of the American Association of Workers for the Blind, Howe's manager, Frank Bryan, was generous in his praise. The Foundation's braillewriter, he said, "has everything one could want for brailling and is a real boon to the cause." By the time World War II requirements restricted the supply of aluminum for civilian use, 1,500 Foundation braillewriters had been distributed. In the midst of the war the Outlook published an emergency appeal for people to sell back machines no longer in use, but the yield was small. For the most part, blind civilians had to make do with whatever they had. However, in early 1945 a special dispensation was secured from the war production authorities for manufacture of braillewriters for blinded servicemen, and 900 Foundation machines were produced for this purpose that year and the next.

Well before wartime restrictions halted production of this braillewriter, efforts were under way to seek further convenience for blind users in the form of a smaller, lighter machine that might fit into a person's pocket or briefcase. Toward the end of 1938 a young engineer named Raymond Lavender constructed a crude model of a miniature machine weighing less than three pounds. It had serious deficiencies, but was regarded as sufficiently promising to warrant further investigation. In the course of the next two years, the Foundation advanced several thousand dollars in grants to the inventor in exchange for title to the finished product. The results were unsatisfactory, and the project was dropped in late 1941 when Lavender, who had accepted wartime employment with a large industrial firm, became unavailable for further experimentation.

Robert Irwin, who never gave up easily, applied to the Carnegie Corporation for a grant to go on with the development of a lightweight, compact machine. An urgent need existed. The Foundation braillewriter weighed 16 pounds, even though it was largely made of aluminum. "Now that aluminum is well nigh impossible to obtain, it will be necessary to cast the machine of iron, which will make it so heavy as to be no longer portable," Irwin wrote on October 8, 1941, in requesting $6,000 to perfect a writer that could be carried about conveniently, and an additional grant of $15,000 to begin manufacture of such a model when designed. The Carnegie people agreed to the development grant and left the way open for a later application to finance the tooling up. By this time, however, the United States was fully at war and neither skilled labor nor raw materials could be had for non-essential enterprises.

In 1945 the Foundation contracted with the Armour Research Foundation of the Illinois Institute of Technology to complete development of a lightweight writer. The Armour people started with the Lavender machine but soon abandoned it. Several new designs were tried out during the following two years, but not one measured up. In the end, failure had to be acknowledged.

At this point there was a turnaround that spoke well of the growing spirit of unity and cooperation in work for the blind. During the war years an engineer associated with the Howe Memorial Press of the Perkins School had developed a nine-pound braillewriter designed on entirely new principles. In 1947 a working model of this device, called the Perkins Brailler, so impressed the Foundation that it voted to endorse the new machine and terminate efforts to produce a new model of its own. The Foundation went even further by persuading the Carnegie Corporation to allocate to the Perkins Brailler the $15,000 tooling grant half-promised to the Foundation six years earlier. This would be matched by a similar sum to be raised by Perkins.

By the end of October 1949, M. Robert Barnett, who had then just succeeded Irwin as executive director of the Foundation, was able to report to the Carnegie Corporation that the first Perkins Braillers would come off the assembly line in the spring. As an earnest of the Foundation's confidence, he noted, it had placed an order for 500 machines for resale, thus providing Perkins with an assured market for their initial production run.

Over the years the Perkins Brailler has proved its excellence; it has become the most popular machine of its kind, with sales far outrunning two other American-made braillewriting machines. One of these is the New Hall Braillewriter, which the American Printing House redesigned after the war; the other, surprisingly enough, is the Lavender Writer. Raymond Lavender reappeared in the world of work for the blind in 1950, by which time he had redesigned his small machine and elicited interest from several major braille houses. In the course of the next decade, the Lavender writer was finally perfected; in 1962 it began to be manufactured and marketed by the American Printing House for the Blind. It was the lowest-priced of the three American machines, but weighed only a half-pound less than the Perkins Brailler. A truly pocket-sized braillewriter was still awaiting invention in 1972.

The third aspect of braille production in which the Foundation experimental shop achieved useful progress was the Garin process.

Maurice Garin was a French engineer who invented a method of duplicating hand-transcribed braille. It consisted of filling the pitted side of a page of braille manuscript with a mixture of plaster and glue. This fixed in place the raised dots on the other side and hardened the paper sufficiently to serve as a printing plate from which 50 or more copies could be struck.

A process of this sort was of great importance in France and other European countries, where hand-transcribing had long been a major resource of library collections for the blind. In the United States, however, hand-copying did not begin in earnest until World War I, when blinded servicemen required literature in the newly adopted braille Grade 1½. Mrs. Gertrude T. Rider, head of the Reading Room for the Blind in the Library of Congress, was put in charge of the library at Evergreen, where she trained volunteers to braille stories, news reports, and anything else the trainees asked for by way of reading material. By 1920, Evergreen reported that its braille library held 500 press-made and an equal number of hand-copied volumes. By the time it closed its doors in 1925, it possessed 1,500 volumes; these were transferred to the Library of Congress, where Mrs. Rider and her staff continued to circulate them by mail to the discharged men as well as to other blind readers.

Hand-copied books, however, were hardly a total answer to the needs of several hundred blinded men, so at the same time that Mrs. Rider was organizing a volunteer corps of hand copiers, she invoked the help of the Committee on War Services of the American Library Association in securing funds for press-brailling. As the American Foundation for the Blind was to do, the Library Association asked authors, publishers, clubs, and individuals to finance the cost of embossing books in the new typeface. Many authors responded generously by paying for the brailling of their own works. Booth Tarkington gave $300 for the embossing of Penrod; Mary Roberts Rinehart sent a check for $500 to make the plates for her newest book, Love Stories. Civic organizations and philanthropic individuals financed not only fiction but books on practical aspects of making a living for blind men.

The Library Association's interest was not limited to the war-blinded. At the same time that the newly press-brailled volumes in braille Grade 1½ swelled the Evergreen collection, copies went to the principal libraries which circulated books for the civilian blind.

It was in promoting the hand-copying of books by volunteers, however, that Mrs. Rider made her greatest contribution. Starting with a woman who turned up at Evergreen, she discovered that motivated people could be trained in a few weeks of concentrated study to produce readable braille. Through the Red Cross she had access to a nationwide network of women, eager to serve, who needed only to be told what to do and how to do it. By 1921, when the national board of the American Red Cross officially adopted braille transcribing as part of its volunteer service, there were already 25 chapters in 13 states and the District of Columbia enthusiastically pounding away at braillewriters. The volunteers contributed not only time and effort but, in most instances, bought their own braillewriting machines and supplies of braille paper.

As head of the Reading Room for the Blind in the Library of Congress, Mrs. Rider was in a position to combine the library's facilities with Red Cross manpower to develop correspondence courses in braille transcribing for the guidance of the volunteers. Handbooks for proofreading were also published, and a certifying system was established. A volunteer braillist won her certificate to make permanent transcriptions by submitting 50 pages of accurate and neatly transcribed work. In the early days, all volunteer transcriptions were sent to Washington, where the pages were corrected, shellacked, numbered, collated, and bound into volumes before presentation to a library. Much of the work, particularly the proofreading and correcting, was done by blind people paid out of Red Cross funds. The collating and other processing tasks were handled for the most part by volunteers from the District of Columbia chapter of the Red Cross.

So much care and thought went into this entire movement that someone even found an ingenious use for the test sheets submitted by would-be braillists. These were sent to blind people who had tuberculosis or other communicable diseases which barred them from participating in the regular circulating book system.

The principal drawback of hand-transcribing was that hundreds of hours of volunteer labor produced but a single copy of a book. The Garin duplicating process had become known in the United States shortly after the end of the war, but due to the differences between American and European brailling methods, the process needed modification before it could be used.

When the Foundation sent its team of technical experts abroad in 1924 to investigate braille production methods, one of the team's purposes was to look into the Garin process. Robert Irwin got in touch with the inventor in Paris and commissioned him to work out adaptations of his equipment to fit American requirements. One adaptation involved page size, since American transcribers used a different number of characters per line and lines per page. The other problem to be solved was somewhat more intricate. European hand-transcribers preparing material to be duplicated worked with a slate and stylus, whereas American volunteer copyists were accustomed to working on braillewriting machines. However, there was one style of braillewriter, a British model, that could be modified to accommodate the Garin equipment, and Irwin arranged to have it sent from London to Paris, so that Garin might work out the necessary mechanical adjustments. This was eventually accomplished.

Because it was tricky to handle and produced uneven results at best, and because it did not lend itself to two-sided printing, the Garin process was only partially successful in duplicating books. Its real usefulness proved to be as the braille equivalent of the mimeograph for making multiple copies of school examination papers, circular letters and other short-lived materials. It had the further advantage of being inexpensive. Ultimately the development of plastics following World War II made possible a vacuum-forming process which allowed hand-transcribed materials to be mechanically duplicated.

By the time Gertrude Rider retired from professional life at the end of 1925, she had certified 900 volunteer braille transcribers in 149 Red Cross chapters and other women's groups from Maine to California. She had also seen a change in the distribution system that greatly stimulated the continuing interest of the volunteers once the appeal of blinded soldiers had abated. Hand-transcribed manuscripts were no longer solely collected and distributed through the Library of Congress in Washington; groups working in large cities which housed major libraries for the blind had the option of working for and with these local institutions. Volunteers not only brailled for their local libraries but helped out in the processing, collating and binding of the finished volumes.

Succeeding Mrs. Rider at the Library of Congress was Adelia M. Hoyt, a blind woman who had been her assistant since 1913. Under Miss Hoyt's direction the braille transcribing service was maintained at a high level and after 1932 was safely shepherded through the transition from Grade 1½ to Standard English braille. Two years after Miss Hoyt's retirement in 1938, she was awarded the Foundation's Migel Medal in recognition of her achievements. A few years later, a Foundation medal was presented to a layman whose leadership in hand-copying of books for the blind antedated even Mrs. Rider's. This was Harold T. Clark, a Cleveland lawyer, who, before World War I, had organized a volunteer corps of braillists under the banner of the Cleveland Society for the Blind and kept it going until the service was officially adopted by the Red Cross.

One of the first coordinating services undertaken by the Foundation immediately after its establishment was the compilation and maintenance of a card catalog called the Embosser's List. It served as a clearing house of braille books published anywhere in the United States. To prevent duplication of titles, all braille printers registered their books with the Foundation and refrained from beginning work on a new title until they had ascertained, by means of the catalog, that it had not already been brailled elsewhere. Each issue of the Outlook printed a list of newly press-brailled books so that librarians, schools, and agencies serving blind adults might know what was available, and where.

Where hand-transcribed books were concerned, so long as all of these were processed by the Library of Congress, an automatic clearing house was in effect. Once volunteer transcribing was decentralized, however, the need arose to prevent duplication of titles in hand-copied as well as press-brailled books. Initiative toward this end was taken by the American Library Association's Committee on Work for the Blind under the chairmanship of Lucille A. Goldthwaite, librarian for the blind of the New York Public Library. Lists of the hand-copied books in the possession of various local libraries were compiled by Miss Goldthwaite and published regularly in the Outlook beginning with the March 1927 issue.

The Outlook stopped printing these lists at the end of 1931, by which time Miss Goldthwaite had begun, under the joint sponsorship of the New York Public Library and the American Braille Press in Paris, a monthly braille magazine, the Braille Book Review, which carried lists of all new press-brailled and hand-copied volumes along with descriptive annotations, reviews, and other book news of interest to finger-readers. Budgetary stringency caused the American Braille Press to withdraw from the partnership in 1934, and the New York Public Library used a small bequest to carry the full cost for some months until the Library of Congress took over a share of the financial responsibility.

Inasmuch as the Review was issued in braille, its contents were not conveniently available to sighted persons who had a professional interest in them. In 1940 the Foundation began to publish a mimeographed version for distribution to libraries, schools, day classes, and agencies for the blind. Miss Goldthwaite, who won a Foundation medal in 1946 for her leadership in creating this useful adjunct to reading for the blind, continued to edit both editions of the Braille Book Review until mid-1951. The last nine years of her editorship were under the auspices of the Foundation, whose staff she joined following her retirement from the New York Public Library in 1942.

The Review went from mimeograph to inkprint in 1953, at which time the Library of Congress assumed the total cost of publication. As of 1972 it was continuing as a bi-monthly, with the editing and distribution of the inkprint edition handled by the Foundation's Publications Division in cooperation with the Library of Congress. The latter likewise financed production of the Review 's braille edition, which also incorporated announcements of books issued in sound-recorded form. The publication was sent free of charge to the 11,000 braille readers registered with regional libraries for the blind.

What was it about brailling that so swiftly attracted the willing eyes and fingers of thousands of volunteers? Part of the answer could be seen in any list of hand-transcribed books. Beyond their sense of service and the fact that the program was begun before press-brailled books were available through federal appropriations—and before the days of recorded books and large-type printing—the women who sat down at their braillewriters forty and fifty years ago had the pleasant task of dealing with contemporary best sellers. A 1927 list of hand-copied books included titles by Michael Arlen, Willa Cather, Rafael Sabatini, P.G. Wodehouse and other popular authors.

The spirit of the early volunteers was perhaps most eloquently expressed in a letter from one of them who wrote, "I should like nothing better on my tombstone than 'She Brailled a Book.' " The appetite for brailling seemed self-renewing. In the Forties a New York agency for the blind reported that a seventy-three-year-old volunteer had transcribed 337 volumes of textbook material, fiction, poetry, and plays—35,302 pages in all—in 13 years, and a New Jersey woman was cited for transcribing 316 children's books in an eight-year period.

World War II brought about an administrative change in volunteer brailling. Preoccupied with other wartime responsibilities, the American Red Cross discontinued its sponsorship of the transcribing service and the Library of Congress picked up the national certification program. As had been the case in the years 1914 to 1918, war evoked a new surge of interest in service for the blinded. A nationwide organization of volunteer braillists took shape in 1945. The National Braille Association, which by 1972 had some 2,500 members, conducted workshops for the improvement of transcribing methods, maintained a program for recognizing length of service, made awards for outstanding accomplishment, and met regularly with organizations engaged in all types of work for the blind.

The appreciable extent to which hand-copied books continue to swell the range of literature available to finger-readers can be seen in almost any contemporary issue of the Braille Book Review. Of the 775 new braille titles put into circulation during 1970, nearly 600 were hand-copied. In addition to the national program of the Library of Congress, major hand-transcribing programs offering nationwide circulation are currently conducted by three large public libraries—New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago—and three voluntary organizations in New York City—the Jewish Braille Institute, the Jewish Guild for the Blind, and the Xavier Society for the Blind. The denominational auspices of these agencies are not reflected in their book transcriptions, which are mostly of a general and nonsectarian nature.

One of the most significant by-products of the volunteer braillist movement has been the overflow of interest into other aspects of service for blind people. Local agencies—often the instruction and training centers for volunteer braillists—have benefited from their contact with a corps of dedicated, deeply committed members of the community who constitute a unique and precious bridge between blind people and the sighted world.

The work of volunteer braillists in the Seventies includes a substantial volume of technical and reference books and periodicals which are indispensable to blind students pursuing an education, to professional workers whose careers require keeping up with the technical literature in their particular fields, to scholars who need special reference material. While the development of other channels of communication has lessened the blind person's overall dependence on finger-reading, nothing has yet replaced Louis Braille's six-dot cell as a basic medium for serious study.