Chapter 25: The Loneliest People

Helen Keller called them "the loneliest people on earth." Gabriel Farrell termed them "children of the silent night." "The muffled drums" was the name some gave themselves in England.

They were the deaf-blind, regarded by the few people who even knew of their existence as the most hopeless, the most helpless of human creatures, deserving of pity and protection but unreachable, unteachable. It was no wonder that the one such person the world did know about—the one whose life and accomplishments defied the popular stereotype—was regarded as enough of a miraculous oddity to be booked on a vaudeville circuit.

But Helen Keller was not the only person—or even the first—to be helped out of what she described as "the double dungeon of darkness and silence." There were others before her, others came later, and there will doubtless be more in the future, for it was less than thirty years ago that the world began to acknowledge the existence of this heretofore hidden layer of humanity. And with that acknowledgment came new efforts at rescue and salvage—efforts spurred on by Helen herself in the face of decades of discouragement.

As of 1972, the number of known deaf-blind persons in the United States was put at 12,000, equally divided between children and adults. Knowledgeable authorities estimated that there were at least 3,000, and perhaps as many as 8,000, additional deaf-blind persons who had not yet been located.

Of the known population, relatively few were in Helen Keller's condition, i.e., totally without sight or hearing. Although the language varied somewhat from situation to situation, the basic definition of deaf-blindness was "legal blindness plus inability to understand connected discourse through the ear, even with amplification." This meant that many deaf-blind persons had traces of vision or faint degrees of hearing, or both, but that neither sensory channel was sufficiently functional to serve by itself or as a substitute for the other. It was the absence of the substitution factor that made deaf-blindness so disabling a condition.

As with simple blindness or simple deafness, the kind and extent of handicap were governed by individual factors. Degree of loss, as well as age of onset and the order in which the disabilities occurred, all made a difference. It was the rare deaf-blind person who was born that way. At one time, childhood infections such as scarlet fever or meningitis sometimes produced simultaneous blindness and deafness, but in later years, when raging infections of this type had been largely eradicated, simultaneous onset seldom occurred. Judging by contemporary sample studies of segments of the adult deaf-blind population, deafness more often preceded blindness than vice-versa; the interval before the onset of the second disability ranged from a few years to a good many.

The person who grew up as a deaf child and then lost the use of his eyes had visual memories to draw upon but had learned to be dependent on vision to receive (and usually to give) communication by means of sign language or lip reading. The situation was reversed for the blind person who subsequently lost the hearing that had been his main source of orientation and communication. The age at which first one and then the other sensory channel was blocked was also a crucial factor in the nature and dimension of the overall problem confronting the individual. The person beset with deaf-blindness in adulthood, after he had had an education, was in a very different plight from the preschool child who still had everything to learn.

This is perhaps the point at which to dispose of the "darkness and silence" image evoked by the popular catch phrases used to describe deaf-blindness. An English business executive who lost his hearing in young adulthood and, a dozen years later, was blinded in an automobile accident, wrote a compelling account of his experiences and sensations during the first months of double disability—"a period of furious frustration"—and went on to describe the world as he perceived it:

What is it actually like to be deaf-blind? I can only tell you what it is like for me. What it's like for a person who has never seen or heard, I do not know.

First, it is neither "dark" nor "silent." If you were to go out into a London fog—one of the thick yellow variety—and then close your eyes, you would see what I see. A dull, flesh—colored opacity. So much for literal "darkness. … "

Nor is my world "silent" (most of us wish it were so!) You have all put a shell to your ear as children and "listened to the waves." You may, at times—when dropping off to sleep perhaps—have "heard" the clang of a bell in your ear, or a sound like the shunting of railway wagons, or a shrill whistle, or the wind moaning round the eaves on Christmas Eve. All these have I perpetually. They have become part of the background. Cracklings, squeakings, rumblings—what I hear is the machinery of my being working. The blood rushing through my veins, and little cracklings of nerves and muscles as they expand and contract. In short, my hearing has "turned inwards."

This man had a bank of visual and auditory memories on which to draw. Severe as they were, his problems were less devastating than those of a person whose congenital or early deafness rendered him unfamiliar with sound and gave him an absent or imperfect command of speech, or a person whose lifelong blindness resulted in a limited, perhaps distorted, grasp of objects and spatial relationships.

All told, it was this lack of homogeneity in a sparse, widely scattered and often hidden population that for so long baffled and discouraged those who strove to release deaf-blind individuals from the bonds of personal and social isolation. It was next to impossible to devise methods of education or rehabilitation that could be universally applied.

Those same eighteenth-century philosophers whose metaphysical inquiries into the nature of intelligence led them to speculate on whether a blind person, restored to sight, could recognize visually the objects he knew intimately through touch also pondered the theoretical question of whether it was possible to educate anyone who lacked access to the two principal avenues of knowledge. The two French clergymen who were pioneers in devising an instructional system for the deaf were interested in pursuing this inquiry, but neither succeeded in locating a suitable deaf-blind subject. In the United States, the American Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, which Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet founded in 1817 after studying the methods developed in France, did have such a subject, a young woman named Julia Brace, but little progress was made in teaching her anything but the simplest kinds of self-care. The reason may well have been that although Julia had lost sight and hearing at the age of four, she was eighteen before she became a pupil at Gallaudet's school in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1825.

Samuel Gridley Howe apparently saw Julia soon after opening his school for the blind in Boston in 1832; he wrote of "closely watching" her and concluding that the effort to penetrate the mind of such a person "should not be abandoned, though it had failed in her case as well as in all that had been recorded before."

It did not take long before Howe came upon his chance to succeed where others had failed. In 1837 he was escorted to a New Hampshire farmhouse where he met seven-year-old Laura Bridgman—deaf, blind, incapable of speech, and nearly devoid of the sense of smell, all due to a virulent bout of scarlet fever that had nearly taken her life when she was a two-year-old baby. Moved by the child's plight, and intrigued by the challenge she presented, Howe persuaded Laura's parents to entrust her to his care.

Laura was an appealing little girl—slender and fair, with delicate features—and Howe, who had yet to marry and have children of his own, had a fatherly fondness for her. But his motivation in attempting to open her mind had religious and intellectual as well as humanitarian considerations. Charles Darwin had not yet written his Origin of Species, but the startlingly heretical theory of man's evolution from primates was already being promulgated and Howe was among those who held that the God-given human soul was what distinguished men from beasts. His descriptions of his experiences in teaching Laura emphasized his spiritual convictions. His early efforts—taking a few common objects, attaching to them labels that spelled out their names in raised letters, and training Laura to associate the shape of each word with the object to which it was attached—these, he wrote, involved only imitation and memory. "The process had been mechanical and the success about as great as teaching a very knowing dog a variety of tricks." It was not until Laura had been taught to recognize the individual letters of the alphabet, had learned to pick out and arrange into word form the letters that she associated with particular objects, and had become aware that these letters could be used in different combinations to denote different objects that, as Howe put it,

the truth began to flash upon her—her intellect began to work—she perceived that here was a way by which she could herself make up a sign of anything that was in her own mind and show it to another mind; and at once her countenance lighted up with a human expression: it was no longer a dog, or parrot,—it was an immortal spirit, eagerly seizing upon a new link of union with other spirits!

Years later, in his memorable Batavia address, Howe recapitulated his work with Laura and threw down an even more direct challenge to the Darwinists: "She took hold of the thread by which I would lead her out, because she had all the special attributes of a human soul. No created being devoid of these attributes could do it. Try ye, who believe that an ape or a chimpanzee differs only a degree from man!"

After the first weeks, during which Howe personally taught Laura, he assigned a special teacher to work with her under his direction. The next step was to teach her that there was a different and faster way to represent the letters of the alphabet than by laboriously picking out their shapes in cast metal. This was the manual alphabet of the deaf, in which fingers held in different positions and combinations signified the 26 letters. Laura learned how to receive and give these finger signals and thus was forged the third link in the chain of communication that freed her from isolation. Other links were added. She was taught to read books embossed in Howe's raised type, to write with a pencil using a grooved board to guide the lines, to do simple arithmetic, and to master sewing and other kinds of handwork. There was no effort to teach her the use of voice; Howe later said he regretted not having made the attempt, but too many other things were then claiming his attention, among them his marriage to Julia Ward in 1843. Laura's main communication channel remained finger-spelling, at which she became adept, and many of the blind children at Perkins (including Anne Sullivan) learned the manual alphabet so they could converse with Laura and, later, with the four other deaf-blind children taken into Perkins during Howe's lifetime.

Laura Bridgman outlived her benefactor by 13 years, remaining at Perkins until her death in 1889. After two attempts to return her to her family proved unsuccessful, Howe left a provision in his will to insure she would continue to be sheltered at the school to the end of her life. She was by no means a liability. In fact, the attention called to her by Charles Dickens in American Notes brought Perkins world renown. (The novelist, who visited the school in 1842, "did not deign to notice anything or anybody except Laura," one of the girl's teachers observed in her diary.)

Dickens' enthusiasm, remarkable in a man so outspokenly critical of institutions, was the fortuitous factor that opened the gates of liberation for Helen Keller. As pointed out in an earlier chapter, it was reading American Notes forty-plus years later that prompted Helen's parents to begin the inquiries that led to Anne Sullivan, who spent six months studying Howe's reports on the instruction of Laura Bridgman, and talking with the aging Laura herself, before heading south to Alabama in March 1887.

Anne Sullivan, whose teaching techniques were brilliantly intuitive, carried Howe's methods a long step forward when she decided to communicate with seven-year-old Helen in complete sentences rather than teach her isolated words. This insight came to her barely a month after her arrival at the Keller home. On April 10, 1887, she wrote:

I am going to treat Helen exactly like a two-year-old child. … I asked myself, "How does a normal child learn language?" The answer was simple, "By imitation." The child comes into the world with the ability to learn, and he learns of himself, provided he is supplied with sufficient outward stimulus. He sees people do things, and he tries to do them. He hears others speak, and he tries to speak. But long before he utters his first word, he understands what is said to him. I have been observing Helen's little cousin lately. She is about fifteen months old, and already understands a great deal. … She obeys many commands like these: "Come," "Kiss," "Go to papa," "Shut the door," "Give me the biscuit." But I have not heard her try to say any of these words, although they have been repeated hundreds of times in her hearing, and it is evident that she understands them. These observations have given me a clue to the method to be followed in teaching Helen language. I shall talk into her hand as we talk into the baby's ears. I shall assume that she has the normal child's capacity of assimilation and imitation. I shall use complete sentences in talking to her. …

Two weeks later she was able to report:

The new scheme works splendidly. Helen knows the meaning of more than a hundred words now, and learns new ones daily without the slightest suspicion that she is performing a most difficult feat. She learns because she can't help it, just as the bird learns to fly. … [W]hen I spell into her hand "Give me some bread," she hands me the bread, or if I say, "Get your hat and we will go to walk," she obeys instantly. The two words, "hat" and "walk" would have the same effect; but the whole sentence, repeated many times during the day, must in time impress itself upon the brain, and by and by she will use it herself.

It seems reasonable to conjecture that this creative concept contributed heavily to Helen Keller's masterly command of language. Her ability to express herself in graceful, often poetic, prose far outstripped the childish constructions in the journals the adult Laura Bridgman kept. It was not merely a matter of advanced education. Helen was not yet ten years old when she sent an impulsive letter to the poet John Greenleaf Whittier with sentences like these: "When I walk out in my garden I cannot see the beautiful flowers but I know that they are all around me; for is not the air sweet with their fragrance? I know too that the tiny lily-bells are whispering pretty secrets to their companions else they would not look so happy."

Her teacher may have helped Helen with this and comparable letters (indeed, it was alleged by some that she dictated them), but how, then, explain the talent for expression in the letters Helen sent Anne Sullivan during a long summer separation? Months before the letter to Whittier, Helen wrote from Tuscumbia to "Dearest Teacher":

I am sitting on the piazza, and my little white pigeon is perched on the back of my chair, watching me write. Her little brown mate has flown away with the other birds. … Little Arthur is growing very fast. … I will take his soft chubby hand in mine and go out in the bright sunshine with him. He will pull the largest roses and chase the gayest butterflies.

It was the following winter, when Helen and her teacher were in residence at Perkins, that they heard of a deaf-blind girl in Norway, Ragnhild Kaata, who had been taught to speak. The headmaster of the school for the deaf in which Ragnhild was a pupil anticipated what is now called the vibration method by placing the six-year-old girl's hands on his lips so that she could feel and imitate their movements. Helen at once aspired to a comparable achievement and for a number of years took speech lessons, first from a private teacher, then at a school for the deaf and, later, again from private teachers as well as from Anne Sullivan. It was a milestone in her young life when, at the end of the first 11 lessons, she was able to articulate "I am not dumb now," but the enunciation was halting and garbled, and, as Anne Sullivan's biographer was to write, the aim of Helen and her teacher to have Helen achieve normal speech was

the only one of their heroic undertakings in which they have confessed defeat. It is no secret that Helen's voice is the great disappointment of her life. … To those who are accustomed to it, it is easy to understand and not unpleasant to hear, rather like listening to someone with a queer foreign accent. But strangers, as a rule, do not find it easy to follow.

If there was a single repetitive theme in everything Helen Keller wrote from childhood on, it was the desire that something be done for others afflicted like herself. She instilled this desire in a number of others. Among those who befriended her during her earliest years was William Wade, a well-to-do landowner in western Pennsylvania who became the patron of every deaf-blind child and adult he could find. Wade made no effort to establish an organized channel of help but, in the manner of the times, made individual persons the objects of his private beneficence, distributing books, typewriters, sewing machines, looms, bicycles, dolls, vacation trips, and whatever else seemed calculated to bring pleasure or profit to barren lives.

It was, in fact, through one such impulsive gift that he met Helen in the first place. After reading a letter published in a children's magazine in which she described her small dog, Wade remarked to his sister, "That is not the sort of dog a blind child needs, she ought to have a mastiff." He promptly arranged to send her one, and her letter of thanks, in which she said she planned to name the dog Lioness, began a correspondence between the nine-year-old child and the fifty-year-old philanthropist that led to Helen and her teacher's spending a summer, and later a winter, as guests of the Wade family at their estate in Oakmont, Pennsylvania. Helen's account of their first meeting showed the remarkable sensitivity of her sense of smell: "He met us at the train in Pittsburgh, and I recognized him at once by the tobacco he used, the scent of which had permeated the letters he sent me."

Wade's delight in Helen and his appreciation of what could be accomplished by an eager mind despite the absence of vision and hearing was in line with his long-held interest in the question of deafness. Toward the closing years of his life (he died in 1912 at the age of seventy-five), he wrote a monograph, The Deaf-Blind, which was the first effort at constructing a roster of deaf-blind persons in the United States, giving an account of their education, their accomplishments, and their status. The first edition of this book, published in 1901, listed 72 such persons Wade either knew or had heard of; in a second edition, published three years later, the list came to 110 names, the majority supplied by schools for the deaf.

The huge dog Wade gave Helen also managed to play an incidental role in the history of work for the deaf-blind. A mistaken fear for the public safety caused a policeman to shoot Lioness soon after her arrival in Tuscumbia, and Helen's letter to Wade, reporting this unfortunate event, was published in a magazine at his initiative. It prompted a deluge of spontaneous public subscriptions to buy Helen another dog. But Wade had already sent her a replacement,* so she decided to divert the contributed money to a fund Michael Anagnos was then raising for the upkeep of Thomas Stringer, a four-year-old deaf-blind boy who had just been brought to Perkins from a Pennsylvania almshouse.

Stringer, who spent 20 years at Perkins, became one of the school's legendary figures. His academic accomplishments were modest, but he was extraordinarily adept with his hands and grew into a first-class craftsman in woodworking. Following his graduation from Perkins in 1913, he went to live with a guardian, his economic future secure thanks to the $1,000-a-year income from the fund Anagnos had raised, plus what he earned by constructing vegetable crates for sale to local farmers.

During Perkins' first century, 18 deaf-blind children were educated there, with varying degrees of success. A few other schools for the blind, and a large number of schools for the deaf, also contained pupils with a second disability. Among the best known of these were two educated in schools for the deaf. One was Kathryne Mary Frick, who was graduated in 1925 from the Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and, five years later, came to public notice through an autobiography published in the Atlantic Monthly. The other was Helen May Martin, who was educated at home and in her late teens entered the Kansas School for the Deaf; she was a talented pianist who learned to read music scores in New York Point, memorized them, and made frequent concert appearances throughout the Middle West during the Twenties.

An exceptional case was that of Helen Schultz, who received virtually all of her education in the public schools of New Jersey. She was the subject of an article, "The Education of a Girl Who Cannot See or Hear," which Lydia Hayes, chief of the New Jersey Commission for the Blind, wrote for the Outlook in 1926, describing how Helen attended a public school in Jersey City until she was eleven, when her mother died. She spent the next year at Overbrook and then returned to her home state where, adopted by a family living in suburban Montclair, she completed her education in a local public school. Except for the year she spent at Overbrook, Helen Schultz did not have a private teacher-companion constantly at her side; she made friends with schoolmates and received whatever supplementary help she needed from them, from her teachers, or from those at home, first her mother and then her adoptive guardian. Having had hearing until she was seven, Helen had command of speech. She received communication through the manual alphabet from those who knew it, through printing in her palm from those who didn't.

What Lydia Hayes omitted to mention in her article was that she herself was the person who had adopted Helen. This was made known a few years later when Walter Holmes, editor of the Ziegler Magazine, wrote an article describing Helen's efficient management of the Hayes household. She could cook, sew, knit and crochet in addition to reading braille and using the typewriter. Later she married Lydia Hayes' nephew and moved to the Middle West.

Helen Schultz was exceptional because, until 1931, deaf-blind children who received any kind of formal education in a school for the blind or a school for the deaf were assigned to special teachers on a one-to-one basis. One of Gabriel Farrell's first acts as the new director of Perkins was to change that. As he later described this innovation,

instead of employing a teacher for each pupil, a special department was opened with teachers trained in speech-building for schoolroom instruction and attendants to care for the children outside of the classroom. In making this fundamental change, it was hoped to secure more skilled teachers on a professional basis and by distributing responsibility to avoid both the loneliness of Laura Bridgman after her school work terminated and the life-long dependence of Helen Keller upon first Mrs. Macy and later Miss Thompson (sic).

The change at Perkins was not altogether self-generating; it was stimulated, at least partly, by a train of outside events that were then arousing new public interest in the problems of deaf-blindness.

In 1927 a Montreal publisher issued a book, Hors de Sa Prison, in which the author, Corinne Rocheleau, told the chilling story of a deaf-blind girl named Ludivine Lachance. The daughter of illiterate parents living in a remote village in Quebec, Ludivine lost sight and hearing before her third birthday; for the next 13 years she led the life of a half-tamed animal. As summarized in an English-language review of the book:

Her body was clad in but a single garment, more like a sack than an article of clothing; her hair knew neither brush nor comb; her nails were like the talons of the hawk. A small cell-like room was partitioned off for her use in a corner of the kitchen; it had no window and no furniture but a straw ticked bed. The prisoner of darkness would allow no other stick nor stool in her dungeon and broke chair or table if such were introduced. When air became a vital necessity, she searched out a crack in the outer wall of the house, and, putting her mouth to it, sucked in great draughts of the refreshing element. She ate like a wild animal, using her hands to convey the food to her mouth, and bolting it without perceptible mastication.

When Ludivine was sixteen, the village curé finally persuaded her parents to let her be taken to the convent school for deaf-mutes in Montreal, conducted by the Sisters of Providence. There, for the remaining seven years of her life (she died of tuberculosis in 1918), the half-crazed, half-savage Ludivine was patiently brought by devoted nuns to a semblance of human dignity. She was taught cleanliness, self-care, some rudiments of language, a few manual accomplishments, and was instructed, to the limits of her understanding, in the Catholic faith.

It is not clear whether the author of Ludivine's story, a deaf woman who was herself a graduate of the convent school, knew Ludivine, but she apparently did know the nuns who had taught her and a number of other deaf-blind girls brought up under their care. Preparing to write her book, Corinne Rocheleau sent inquiries to schools for the deaf and schools for the blind in both Canada and the United States, asking about any deaf-blind pupils they might have had. Her researches led her to a Cincinnati woman, Rebecca Mack, who had also long been interested in the welfare of the deaf-blind and had begun to keep a list of all such persons who came to her notice. The two women joined forces to compile a register of 655 names of deaf-blind children and adults; their idea was to publish these in book form, much as William Wade had done early in the century.

The field of work for the blind became aware of this project when, in September 1928, the Outlook published a long article by Miss Rocheleau describing her researches and pleading for joint action by organizations concerned with the blind and those concerned with the deaf. Interest in the subject was heightened when, soon thereafter, Sherman C. Swift devoted his "Book News" column in the Outlook to a detailed synopsis of Hors de Sa Prison which, having been published in French, was not widely known in the United States. That same year saw the publication of a new book, Laura Bridgman, the Story of an Opened Door, by Laura Richards, daughter of Samuel G. Howe. The second installment of Helen Keller's autobiography, Midstream, appeared around the same time.

The two professional associations in work for the blind took note of these stirrings. In 1928 the AAIB voted to appoint a committee of three "to cooperate with a like committee from the National Association of Instructors of the Deaf to consider the feasibility of a sane plan for the education of the deaf-blind." When the AAWB met the following summer, it went beyond the question of education to consider the overall dimensions of the problem. Two important points were brought out in the summary of its discussions:

No plan of education for the deaf-blind would be complete without the giving of some consideration to after care, since the plight of the adult deaf-blind is recognized to be quite as serious as his plight as a child. Over-education without means of self-realization for social adjustment was stressed as holding grave possibilities for unhappiness in the individual.

There was less agreement as to a solution. … A more or less centralized plan for the education of the deaf-blind might have its advantages, but whether an independent institution should be built and maintained for this purpose, or whether the work should be done in conjunction with certain schools for the deaf, the blind, or the deaf and blind already established, seemed open to question. …

The opinion was unanimous, however, that the question was one deserving the careful study of the American Foundation for the Blind.

The Foundation was already in the picture. It had been approached by the Volta Bureau, research arm of the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (later known as the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf) to co-sponsor publication of the Rocheleau-Mack book and had, in fact, voted some money on condition that the published material consist only of the 55-page introductory section in which Corinne Rocheleau outlined the overall problems of deaf-blind persons and the existing provisions for help to them. The Foundation objected to publication of the 110-page "biographical section" prepared by Miss Mack on the grounds that its listing of 665 deaf-blind persons was inadequately documented.

This suggested excision was not acceptable to the authors of Those in the Dark Silence and in 1930 the full text appeared under the Volta Bureau imprint, with the publishing costs underwritten by Miss Mack, a woman of some means. The book was a curious piece of work. Nine out of ten listings in the "biographical section" gave only initials and the name of the state in which the subject lived, and most of these entries were meaningless: e.g., "S.S., New York. Adult. Reads embossed type. Typewrites." or "I.W., Georgia, Adult. Lives with her mother." Only 65 or so entries were identified by name; their biographical information consisted of sketches supplied by the subject, or a member of the family, or his or her teacher, or material derived from press clippings. The explanation the authors gave was that names had been used only with express permission.

Despite its grotesqueries, publication of Those in the Dark Silence served a purpose. Deaf-blindness was the subject of one of the round-table discussions at the 1931 World Conference on the Welfare of the Blind and a formal recommendation was made that the major organizations interested in work for the deaf and work for the blind join forces to tackle the problem. The Foundation thereupon opened negotiations with the Volta Bureau and with the American Federation of Organizations for the Hard of Hearing, and in the closing days of 1931 the three agencies announced the formation of a Joint Committee on the Deaf-Blind.

A three-pronged approach was agreed upon. The Volta Bureau would establish a national register of deaf-blind persons, using the Rocheleau-Mack lists as its nucleus. The hard-of-hearing group, which had chapters in many different cities, would verify and update the register by interviewing persons on the list to determine their situations and their needs. The Foundation's role would be to devise model laws and to campaign for state legislation to initiate or improve provisions for the education of deaf-blind children and the care of deaf-blind adults.

Two representatives of each of the three organizations made up the membership of the Joint Committee on the Deaf-Blind. The chairman was H. M. McManaway, superintendent of Virginia's dual school for the deaf and the blind and president of the Volta Bureau's parent organization. Corinne Rocheleau (she had now become Mrs. Wilfred Rouleau) was the Volta Bureau's other nominee. The American Federation of Organizations for the Hard of Hearing was represented by its executive director, Betty Wright, and another staff member. The Foundation members were Anne Sullivan Macy and Robert B. Irwin, who was named secretary of the joint committee.

It all sounded very promising, but the committee was star-crossed from the outset. None of the three constituent organizations had the money to do a real job. The Volta Bureau, which held a legal option on the contents of the Rocheleau-Mack register, had been unable to find a source of funds to get it into shape. This immobilized the hard-of-hearing group's assignment, and frustrated the Foundation, which needed accurate names and addresses of deaf-blind persons in any given state before it could launch effective action in that state's legislature. There were personality clashes, mainly between Mrs. Rouleau and Mrs. Macy, which brought in Rebecca Mack on the one side and Helen Keller on the other. These came to a head in charges and countercharges, some substantive and others petty, in an angry six-way correspondence that also involved M. C. Migel and Robert Irwin. The upshot was the Foundation's decision in early 1933 to withdraw from the joint committee and to proceed on its own to build a register of the nation's deaf-blind population, on the strength of which legislative initiatives could be pursued.

A few years later Rebecca Mack relented, largely at the urging of Helen Keller with whom she had long been acquainted. She had kept a duplicate of the register and in 1936 gave it to the Foundation, which made an effort to validate it by means of a detailed questionnaire sent to every state welfare department, school for the blind, and school for the deaf.

The results were disappointingly scanty, and resources were lacking to conduct the case-by-case field investigations that would have been productive. The Foundation, then striving to complete its own endowment fund, was unwilling to deflect attention from what it considered its primary responsibility to several hundred thousand blind people by mounting a special campaign on behalf of a much smaller number of deaf-blind persons. But it did make some sporadic attempts to obtain extra-budgetary grants; in 1931 an approach was made to the W. K. Kellogg Child Welfare Foundation and some years later, when the Will Rogers Memorial Fund for handicapped children was established in tribute to the journalist who had died in an airplane crash in Alaska, Helen Keller solicited the fund's trustees for an allocation on behalf of deaf-blind children. Neither effort brought results.

One small windfall did come about; in 1932, when Helen was chosen by Pictorial Review as that year's "woman who has contributed most to womanhood and humanity," the honor was accompanied by a $5,000 award. Helen turned the money over to the Foundation as an earmarked fund to be spent at her discretion for help to individual deaf-blind persons. Beyond this, and an occasional small appropriation from the Foundation treasury to supply deaf-blind individuals with such items as braillewriters, no further efforts were made on a national scale for the next ten years.

Why did this first national effort to join forces with organizations interested in the deaf turn out to be such a fiasco? Migel, who hastily took himself out of the picture, no doubt regarded the whole matter as a squabble among temperamental women. Irwin's motivations for withdrawing the Foundation from the Joint Committee for the Deaf-Blind were a little more complex, but neither man wished to become embroiled in what was essentially a long-standing animosity toward Anne Sullivan Macy by the educators of the deaf.

From early on, Helen Keller's outspoken teacher had criticized the methods used in schools for the deaf. In the two years, 1894–96, that Helen attended the newly opened Wright-Humason school for oral teaching of the deaf, Anne had written to John Hitz, the first director of the Volta Bureau, deploring the "plodding pursuit of knowledge" of the children in the school and the "stupidities" practiced by their teachers. This hardly endeared her to the teachers of the deaf, and they found equally offensive the patronizing tone in which she sought to find excuses for them: "I pity them more than I blame them. When you consider the huge doses of knowledge which they are expected to pour into the brains of their small pupils, you cannot demand of them initiative or originality." Nor did it please them to learn that Alexander Graham Bell, founder of the Volta Bureau, was "so delighted" with Anne's comments that he invited her to prepare a paper on the subject for the next convention of teachers of the deaf.

When, in 1901, William Wade published the first edition of The Deaf-Blind, his prefatory remarks reflected the resentment of educators of the deaf against the widely publicized statements that Anne Sullivan had wrought a miracle in bringing awareness of language to Helen Keller:

The education of the blind-deaf is by no means the difficult task commonly believed. It may be said positively that any good teacher … is fully qualified to teach a blind-deaf pupil, after she learns the manual alphabet. Such a teacher has intelligence, patience and devotion, and these constitute the whole equipment required.

Wade did not spell out what he was aiming at in these remarks, but their meaning was clear to all who knew that a plan was then afoot for the creation of a special school which would serve as a training institute where Helen and Anne would instruct teachers of the deaf-blind in Anne's methods. Helen took Wade's preface to be a denigration of Anne's accomplishments; she also saw it as an effort to thwart this prospect of her gaining a secure livelihood once she graduated from Radcliffe. She was further offended by the fact that among the illustrations in this first edition was a photograph showing her with Arthur Gilman, head of the Cambridge school where she had prepared for college admission. For the sake of her future, Gilman had thought that Helen's day-and-night dependence on her teacher should be terminated, and he had, for a time, succeeded in convincing her mother of this.

Wade was among those of Helen's influential friends who agreed with Gilman (he wrote Helen that he had, in fact, originated the idea and that Gilman was merely his "agent," but Helen chose not to believe this). Others, including Helen's chief financial sponsors, disagreed, and there ensued an anguishing tug of war which ended in victory for Anne Sullivan. Helen regarded the publication of the photograph as a betrayal, and she wrote Wade a reproachful letter:

… in the "Monograph," which came a few days ago, there are indications that you, my dear, kind Mr. Wade, are willing to sacrifice truth and justice to a mere prejudice, and I must utter an indignant protest, though it cost me inexpressible pain. Knowing as you did my feelings towards Mr. Gilman, was it right to ignore them and print a picture of me with him without my consent? This picture stands for something which is gone—something which he killed long ago. When it was taken, I believed that he was a good, true friend. Now I know he was my worst enemy.

In the second and final edition of his book, which appeared in 1904, Wade backed off somewhat. He used a solo photograph of Helen—one showing her capped and gowned for her Radcliffe graduation—and, in a new foreword, went to great lengths to express his admiration for Anne Sullivan's achievements. But he continued to challenge the belief that Anne's educational approach represented a new discovery. By this time, Helen Keller's The Story of My Life had been published and had evoked ecstatic public reactions over Anne Sullivan's role in Helen's education. This troubled Wade, and he wrote a letter to the School Journal insisting "there was no mystery about the education of the blind-deaf, no marvelous genius required, nor any complex intricacies to be unraveled." He reprinted the letter in the second edition of his monograph, along with articles written by other teachers of blind-deaf children describing their methods, which were essentially the same as those of Helen's teacher. He also sought to lay to rest the assertion, voiced by many, that Helen Keller was largely the creature of her teacher's genius. Helen, he said, was a prodigy and it was "dangerous nonsense" to deny it, "for it loads down other teachers of the blind-deaf with the weight of mistaken feeling, that if they could only pursue such methods as Miss Sullivan's, they would make Helen Kellers of their pupils."

Anne Sullivan agreed with him in this last statement and said so repeatedly. As she once put it:

I have never thought that I deserve more praise than other teachers who give the best they have to their pupils. If their earnest efforts have not released an Ariel from the imprisoning oak, it is no doubt because there has not been an Ariel to release.

It was in this second edition of The Deaf-Blind that Wade declared openly what he had only intimated in the foreword to the first edition.

The only thing in "The Story of My Life" that I can see may be mischievous, is the proposal that Helen and Miss Sullivan should carry on a school for the blind-deaf. … The one thing the interests of the blind-deaf demand above all others, is the recognition by the public, and particularly by State boards of education, that it is the duty of the States to educate these unfortunates. If a special school, under the charge of two such distinguished personages, is required to educate the blind-deaf, good-bye to all hopes of the States undertaking it.

Wade's clear-eyed vision of the overall needs of deaf-blind children grew from his intimate knowledge of the field of education of the deaf. He was an original member of the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf and an occasional contributor to its periodicals. At the convention of the American Association of Instructors of the Deaf held in St. Louis in 1904 in connection with the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, he was awarded a gold medal for "his benefactions to deaf-blind children and for his untiring zeal in finding and providing education for such children in the United States."

So much for William Wade. But Corinne Rocheleau and Rebecca Mack regarded themselves as his ideological heirs, asserting that since his death, no one had taken an interest in the deaf-blind. Anne Sullivan Macy may also have seen the two women in this light, and she was not a person who easily forgot or forgave. "Mrs. Macy's stand on the subject of other teachers of the deaf-blind has been most unjust and a constant aggravation to said teachers, many of whom have done work that is truly remarkable," Corinne Rocheleau Rouleau wrote M. C. Migel when the work of the Joint Committee on the Deaf-Blind had reached an impasse. Helen's teacher, she said, "would be a permanent obstacle to harmonious work in the committee." She was piqued by the fact that Mrs. Macy had refused to see her or allow her access to Helen and had scornfully dismissed her as "that French-woman." She could not refrain from slapping back: "I am a perfectly good American by birth and even count Yankee Colonial ancestors, which is probably more than Mrs. Macy could say for herself."

The well-meaning but sometimes maladroit Rebecca Mack also had complaints to make about the way Helen Keller's household treated her. A plaintive letter she wrote Helen brought a rebuke for persistence and a stern lecture castigating the "unfriendly spirit" in which she and Mrs. Rouleau were withholding their register.

It may all have been a tempest in a teapot, but the fact was that as the tempest raged, the teapot boiled dry. A decade passed before it was refilled.

The man who got national action simmering again was the amiable Irishman whose unique blend of idealism, persistence and personal charm had already won him a permanent niche in the annals of work for the blind. Peter J. Salmon, a hero of the workshop campaign which culminated in the Wagner-O'Day Act, played an even more seminal role in the activation of services for the deaf-blind. He did it by means of a well-timed ploy.

In observance of Helen Keller's sixty-fifth birthday in June 1945, Salmon staged a luncheon at the Industrial Home for the Blind, of which he was by then executive director. It was a rather exclusive affair; in addition to Helen, the other principal guests were 13 deaf-blind men trained for employment in the IHB workshop, which had just earned an Army-Navy "E" citation for its war production record. In a statement extensively covered by the press, Helen cited these 13 men who "have all proved their capabilities, strength and human dignity" and urged that training and employment programs similar to IHB's be established in other parts of the nation. This could be done, she suggested, through the cooperative leadership of the Foundation, the IHB, and Perkins.

Months of preparation had preceded this announcement. Still aglow over her recently completed tours of military hospitals, Helen was psychologically ready for a new challenge. The impressive wartime record rolled up by blind and handicapped workers in all types of industry had swept away some long-held prejudices and misconceptions; the climate of public opinion now seemed ripe for an advance. A small but solid body of experience had been built up, largely by IHB, to demonstrate that, given the right kind and amount of help, deaf-blind persons could become productive workers; a similar body of experience proving the educability of deaf-blind children had been developed at Perkins and a few other schools.

The original plan Helen put forward was for a quasi-autonomous body, the National Council for the Deaf-Blind, to be established as an administrative division of the Foundation but financed through a separate campaign. Together with Peter Salmon she outlined a detailed program. Migel was sympathetic. He wrote William Ziegler, Jr., who would succeed him later that year as Foundation president, that "now, in the autumn of her life, we should endeavor to aid [Helen] in this project, which would so greatly add to her happiness and be a gratifying achievement for the Foundation."

The only debatable point was launching a separate organization and a separate campaign; the Foundation decided to set up a new department for the program and to create, instead of the proposed council, an advisory body called the Helen Keller Committee on the Deaf-Blind.

The advisory committee held its first meeting in September 1945, and the new department got under way the following January with Dorothy D. Bryan as director. Mrs. Bryan, whose background included experience in special education, rehabilitation, and social work, began where the efforts of the preceding decade had left off—by initiating a nationwide drive to locate deaf-blind individuals, to ascertain their medical, social, and financial status and, by developing a complete and accurate register, to grasp the extent of the existing needs. The flaw in previous efforts to help the deaf-blind, the committee felt, had been the decision to complete a national register before beginning a service program; this time, the two processes would move ahead simultaneously.

The service program envisaged was primarily stimulation of state and local agencies to care for their deaf-blind populations. However, this proved to be so slow a process that in less than a year the Foundation found itself taking on a direct service role as well. As casefinding went along and urgent needs were uncovered which local resources were not ready or able to meet, the department began to supply hearing aids, vibrator alarm clocks, typewriters, braillewriters, and other tangible aids that could encourage or restore functioning in deaf-blind individuals.

The department's function soon grew even broader. A scholarship program was begun to enable promising deaf-blind young people to go to college. For the benefit of potentially employable adults, a series of short-term courses was financed to bring workshop supervisors from all parts of the country to Brooklyn, where they could learn IHB's tested techniques of communication, rehabilitation and vocational training. To increase educational opportunities for children, courses for teachers of the deaf-blind, cosponsored by Perkins, were conducted for three successive summers at Eastern Michigan University's school of special education.

One of Dorothy Bryan's first observations, as she crisscrossed the nation and visited scores of deaf-blind persons in their homes, was the great hunger for a medium which would help allay their feelings of isolation by providing them with news of the world and each other. In 1947 the Foundation began a monthly magazine, Touch and Go, produced in inkprint and braille and sent free of charge to all deaf-blind adults. In addition to news digests, it contained a variety of articles, stories and poems, many written by its readers.

The national register grew slowly at first. Beginning with fewer than 1,500 verified names, it rose to over 1,900 in 1948. The workload, however, grew fast, and in 1948 Annette Dinsmore was added to the staff as assistant director of the Department of Services to the Deaf-Blind. Two years later she succeeded Mrs. Bryan as director, in which capacity she remained until her retirement in 1971.

Annette Dinsmore was still another example of the right person in the right place at the right time. She began her career as a teacher of deaf children; following the bout of infection that left her totally blind at the age of thirty, she earned a graduate degree in social work, joined the staff of the Philadelphia Department of Public Assistance and then became supervisor of home teaching for the Pennsylvania State Council for the Blind. A tall, sturdy woman with a ready smile, a quick wit, a gift for empathy, and a large fund of common sense, she became to hundreds of deaf-blind people what Kay Gruber had become to the war-blinded: a warm personal friend who kept in touch through intimate correspondence, remembered birthdays and anniversaries, introduced people to others with like interests, and was an unfailingly dependable source of counsel and help in all sorts of situations. She and her Seeing Eye dog became welcome visitors, not only in the households of deaf-blind persons all over the country, but also in the offices of the state and local agencies she persuaded to extend services to them.

Of all the barriers that imprisoned deaf-blind persons, the greatest was difficulty in communication. One of the first steps in the new program was production of a pamphlet, Working with Deaf-Blind Clients, which aimed at bridging the communications gap between staff members of local social agencies and the deaf-blind persons who needed their services. The pamphlet contained a number of simple pointers and was illustrated by photographs showing the finger and knuckle positions of the most feasible communication method, the one-hand manual alphabet. The hand photographed in this pamphlet, issued in 1947, was the hand of Helen Keller.

Two years later, when a more comprehensive guide on the subject was to be issued, an embarrassing discovery was made. Several of the illustrated finger positions were wrong! It fell to Annette Dinsmore to tell Helen Keller that some new photographs would be needed, and to explain why. Annette regarded the assignment with trepidation. If the world's best known deaf-blind person was not the ultimate authority on the manual alphabet, who was? A tactful approach occurred to her en route to Helen's home. The divergences between the standard finger positions and those Helen was accustomed to using were comparable, she explained, to the differences between distinctive individual penmanship and "Palmer Method" handwriting. Amenable to this face-saving explanation, Helen was happy to pose her right hand in the conventional configurations.

The expanded handbook, Methods of Communication with Deaf-Blind People, was issued in 1951 (a revised edition was produced in 1959 and a prize-winning documentary film on the subject was made in 1963). It offered several choices, depending on the individual situation of the deaf-blind person. Those whose deafness had preceded blindness (and they were in the majority) were apt to know the one-hand manual alphabet; those whose disabilities occurred in the reverse order were apt to know braille. Those whose hearing and sight were both lost in middle life or later might not know either, but could nonetheless learn to use one of the simpler methods.

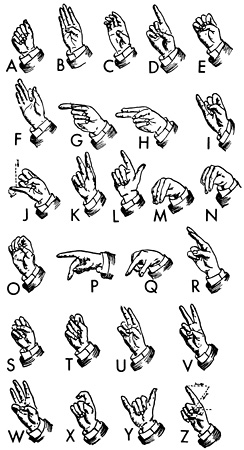

The one-hand manual alphabet had been used for centuries by deaf people. Along with the sign language of the deaf, it was said to have originated in Spanish monasteries whose monks were under a vow of silence. It could be learned in a fairly short time by a sighted or a blind person and had the advantage of relative speed. In the American version, the letter B, for example, was represented by pointing the four fingers, tightly held together, straight up, while the thumb was bent across the palm. To form the letter I the speaker made a fist with the thumb and first three fingers, but pointed the little finger straight up. The various finger positions (see illustration) were formed into the cupped hand of the deaf-blind person.

The British manual alphabet was slightly different. There was also a two-hand alphabet, seldom used because it was awkward and slow.

Some deaf-blind persons received communication by means of the standard Morse Code, which had the advantage of permitting dot-dash touches on any part of the body or even through floor vibrations which could be felt across a room. Another such code, devised by a deaf-blind man named Cross, was based on a system of taps and strokes applied to the back of the hand or elsewhere on the body. It was similar to a dot-and-stroke method developed by the Austrian, Hieronymus Lorm, in the nineteenth century. The Lorm Alphabet was widely used by deaf-blind persons in central Europe.

With a person blind from childhood, it was also possible to communicate through braille hand speech, in which the speaker pointed to the dots in an imaginary braille cell in the receiver's palm, or pressed the receiver's fingertips into braillewriter combinations.

There were also some simple auxiliary aids. One of the oldest was the alphabet glove, which enabled a sighted person to spell out words by touching the letters printed on a thin glove worn by the deaf-blind person. A touch on the top of the thumb was A, one at the base of the ring finger was R, one on the second joint of the index finger was G, etc. This required little effort by the sighted communicator but considerable memorization on the part of the deaf-blind receiver. Easier, but slower, was printing-in-the-palm, which spelled out messages to people who either had a visual memory of print or could be taught to recognize the shapes of printed letters. Slower still were the alphabet plate, which reproduced the print alphabet in embossed form, and the alphabet card, which was embossed with braille letters and overprinted with each letter's inkprint symbol. With these devices the speaker spelled out words by placing the blind person's finger on the correct symbols.

As noted earlier, it took several years to perfect a mechanical device for speedier communication; the problem was finally solved in 1954 by the invention of the Tellatouch, a small machine that enabled a sighted or blind person to communicate with a deaf-blind person who could read braille. Another device was a pocket-sized braillewriter whose output was on a strip of plastic tape. Annette Dinsmore usually took one of these on her field trips, along with a Tellatouch and various types of hearing amplifiers.

An early system for telephone conversations, the Tactaphone, was the product of cooperative work between the Illinois Bell Telephone Company and the Hadley School for the Blind. It required a knowledge of the Morse Code by both parties. The sender used his dial to transmit the code's dots and dashes (dialing number 1 for dot, number 4 for dash) while the deaf-blind person at the other end received the code through his fingertips by means of a vibrating disk installed in the base of his telephone. A later version, the Sensicall, was developed through cooperation of the New York Telephone Company and IHB; it did away with the dialing and permitted the code to be sent either by voice or by means of a separate button. Later still came the Tactile Speech Indicator, a portable device which did not require special installation but could be used with any telephone.

How could a deaf-blind person, alone at home, know there was someone at the door or on the phone? Some had electric fans hooked up to doorbell or phone bell so they could feel the air current activated by the ring. A more modern approach used an electronic instrument, similar to the radio pagers carried by hospital physicians; instead of "beeping," the wireless transmitter, worn in a shirt pocket, vibrated against the body. Two such devices were being tested in 1972, one developed by MIT's Sensory Aids Evaluation and Development Center and the other by Bell & Howell. Even the possibility of group communication among deaf-blind persons was being explored; an experimental European device operated on a relay system similar to that in telephone conference hookups.

Slow and patience-demanding as all of these methods might be, for the socially marooned deaf-blind person they represented a precious lifeline of interpersonal relationship which many had thought lost forever. There were cases where such surrender was needlessly premature—where the fitting of a proper hearing aid made two-way voice communication possible, or where surgical treatment restored vestiges of functional vision.

In the first five years of the Foundation's deaf-blind department, field trips by its staff covered 36 states; five years later, the remaining states had been visited and the volume and quality of local services to deaf-blind adults showed an appreciable upsurge. Field trips invariably resulted in additional casefinding; by 1970 the national register contained the names of 4,000 adults and close to 800 children.

The effort to increase job opportunities was uphill work. In 1956 a national workshop was conducted and a report subsequently published (Vocational Training and Employment of Deaf-Blind Adults), but it failed to have much impact on the state rehabilitation counselors who held the key to jobs. Burdened with large caseloads of less gravely handicapped people who could be trained and placed with less time, effort, and expense, the counselors almost invariably classified deaf-blind applicants as "non-feasible" for employment. It was not until 1962, when the Industrial Home for the Blind put on a full-scale regional research and demonstration program, that the first appreciable dent was made.

More than forty years of service to deaf-blind adults preceded this landmark demonstration. Not long after the youthful Peter Salmon joined the staff of IHB in 1917 as its business manager, a deaf man who had lost his sight applied for a place in the agency's broom shop. Salmon saw no reason not to take him on, and taught the shop supervisor the manual alphabet, which Salmon had picked up during his years as a student at Perkins. This first deaf-blind worker in the broom shop proved so satisfactory that opportunities were given to others as the years went by. As of 1945, a dozen deaf-blind men were employed in the IHB workshop and seven more were receiving other types of rehabilitation services from the parent agency. At this point IHB decided to establish a separate deaf-blind department, and it was the formal opening of this unit, as well as the launching of a national drive, that Helen Keller's 65th birthday luncheon celebrated.

The department's objectives went beyond employment. Almost as urgent as jobs was the need for social contacts and personal development. A program of parties and picnics, games and outings, club activities and hobbies not only enriched the lives of the participants but deepened the insights of the IHB staff into the problems and potentialities of this group.

Sensitive to their human needs, Peter Salmon assumed the role of realistic apologist. "One thing to be kept in mind always," he wrote, "is the fact that no matter how complete the rehabilitation of a deaf-blind person may seem to be, there will always be a certain amount of frustration, irritability, suspicion and restlessness, as a result of the difficult limitations imposed by the double handicap."

Salmon never played down either the difficulties or the gratifications of serving the deaf-blind. The work, he said,

requires patience, compassion, intuition and selflessness far above and beyond that required in work for the blind. The worker must be able to accept trivial demands and childish possessiveness. He must be able to continue when no progress is evident; much of the work with this group is tedious. He must be willing and able to give time—any amount of time; work with the group is slow. And yet, work with no other group is more rewarding in terms of personal satisfaction. Let the worker with the deaf-blind follow through … and he will find himself sharing in the liberation of a soul, an experience granted only to the privileged few.

It was in this spirit that IHB undertook, in 1956, a comprehensive two-year study of 63 deaf-blind clients, their characteristics, limitations and potentials, and in a seven-volume report presented the evidence that intensive rehabilitation could measurably assist the vocational and social adjustment of a large percentage of deaf-blind adults. The findings of the federally financed study occupied a major session at the 1958 AAWB convention. A lead-off statement by Mary Switzer, director of the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, emphasized that it was largely fear that had so long delayed the start of rehabilitation service for this group:

fear among the deaf-blind that their disability placed them automatically on a fringe of society from where there was little chance of escape. … fear among rehabilitation workers … that, because of a lack of guideposts and tools, they were inadequate to cope with the special problems inherent in deaf-blindness.

Thanks to the IHB study, she continued, guideposts were now at hand. It was OVR's hope that rehabilitation agencies in other parts of the country would now enlarge the entrances to opportunity wedged open by the study; the federal government stood ready to back the development of a number of regional rehabilitation centers for the deaf-blind.

Disappointingly, her offer found no takers. An ice-breaker was needed, and in 1962 IHB launched one as a demonstration project—the Anne Sullivan Macy Service for Deaf-Blind Persons, funded by Miss Switzer's agency. Designed to embrace the 15-state northeastern region, the project was called upon to stretch its borders as it progressed; in the end it served clients from 17 additional states, some as far away as Oregon and New Mexico.

Over a period of seven years, and at a cost of $500,000, the Anne Sullivan Macy Service worked with 171 deaf-blind men and women who underwent six-week evaluation periods that were followed, on the average, by eight months of intensive rehabilitation treatment. The results went a long way beyond the findings of IHB's earlier study by demonstrating that, on completion of such a specialized course, deaf-blind men and women could return home to their own communities, or be resettled in new communities, to function with a good deal of independence and self-direction. Optimum results necessitated continuing services from a community agency; one of the most significant effects of the demonstration was that those agencies that had referred clients for rehabilitation showed a marked increase in willingness to work with additional deaf-blind persons. However, as Peter Salmon noted in a monograph which summed up the experience and findings of the project, the real trouble was that many agencies would not take that first step and make a referral for service. "The true failure," he said, "lies in not trying."

No one would ever accuse Peter Salmon himself of not trying. The man in whose honor Helen Keller willed 25 percent of her residuary estate to IHB's deaf-blind program—because, as her last testament stated, she regarded Salmon "as a most active, disinterested champion of the deaf-blind [who] has put unremitting enthusiasm, energy and resourcefulness into the effort to break their captivity of double affliction"—this man was not content to stop with a demonstration project. Already past retirement age, he mobilized and led a five-year legislative campaign which succeeded in incorporating in the 1967 amendments to the Vocational Rehabilitation Act a provision for a federally financed National Center for Deaf-Blind Youths and Adults.

It was not yet the final hurdle. In a general appropriations cutback, the 90th Congress adjourned without approving funds for the center's first year of operations. Striving to remedy the omission as soon as possible, Salmon wrote every federal legislator that, unlike the drastic protest actions of other disadvantaged groups, there would be "no riot or sit-in" on the part of the deaf-blind: "we are dealing with silent men and women who are not only unorganized but so much isolated that they have little knowledge of what is going on. … "

The needed initial appropriation was approved early in the next Congressional session and June 1969 saw the execution of a contract by HEW's Social and Rehabilitation Service assigning operation of the National Center to IHB.

Obtaining funds for construction of the center's residential and treatment facilities also met with a series of frustrating delays. In the original planning, a modest facility had been envisaged at a projected cost of $2.5 million for land and construction. Then a windfall deeded the National Center 25 acres of surplus federal land in Sands Point, Long Island, and a more adequate facility became possible. Zooming construction costs had already made the original sum unrealistic; the added factor of a larger facility meant that $5 million more was needed in building funds. This sum was included in the Rehabilitation Act of 1972, passed by Congress but vetoed by the President. The following year it appeared as an earmarked item in the HEW appropriations bill for fiscal 1973, which likewise met a Presidential veto. Hope remained that the funds would be released in fiscal 1974.

In the interim, the center operated out of temporary quarters. Forced to restrict its client group to 17 or 18 persons at a time, instead of the proposed 50, it was moving ahead with other parts of its overall program: regional offices for case-finding, screening and follow-up; public education activities; and week-long training sessions for staff members of local agencies preparing to serve deaf-blind clients.

Where deaf-blind children were concerned, events followed a different course. Only 133 children—as against ten times that many adults—appeared on the list with which the Foundation's Department of Services to the Deaf-Blind began in 1945. There was every reason to believe that the actual number in both categories was at least twice as large, but whereas some types of immediate service could be offered to adults, there was little that could be done for children without adequate facilities for education.

The deaf-blind department at Perkins, begun in 1932, had been serving an average of 12 to 15 children annually; in 1940 its enrollment reached a high of 18. The New York Institute for the Education of the Blind opened a deaf-blind department at about that time, and in 1943 the California School for the Blind did likewise. An additional handful of children were receiving individual instruction in scattered schools for the deaf as well as in schools for the blind. All told, the nation was educating perhaps three or four dozen deaf-blind children; the rest were immobilized by a pair of tight bottlenecks. There was the reluctance of schools that could cope with a single handicap to take on the complex, expensive, and often frustrating challenge of educating a child with a second sensory deficiency, and there was the absence of qualified teachers who could do the job.

Although the numbers picture was dismal, the prospects for meaningful educational achievement were more hopeful than ever before. Thanks to the pioneering work of a spirited southern woman, Sophia Alcorn, the "Tadoma method" of sensing and replicating sound vibrations was bringing to many deaf-blind children the one gift Helen Keller envied more than anything else—the power of understandable speech.

It was just before World War I that Miss Alcorn, newly graduated from the normal school operated by the Clarke School for the Deaf in Massachusetts, joined the faculty of her native Kentucky's school for the deaf. Soon after her arrival the school accepted its first deaf-blind pupil, eight-year-old Oma Simpson, and assigned the child's training to the new teacher. "Miss Sophie," as she came to be called throughout a long and distinguished career, was dissatisfied with the half-measure represented by the manual alphabet; less than a year after she began with Oma, she started to teach her orally. She placed the child's sensitive fingers on her mouth, jaw and throat to feel the movement and vibrations as different sounds were formed, then had Oma place her fingers on her own face to duplicate these movements and vibrations. During the ten years Oma was in Miss Sophie's charge at the Kentucky school, she learned not only to comprehend speech by "reading" the resonances she felt in touching the speaker's face, but also how to produce speech. "She could carry on a conversation with anyone with whom she came in contact," her teacher wrote.

When the Simpson family left Kentucky, taking Oma with them, Miss Sophie moved, too. At the South Dakota School for the Deaf she met her second deaf-blind child, Tad Chapman, with whom she began oral instruction at once, deferring the manual alphabet stage. Tad was taught words by tactile methods, his fingers tracing the letters his teacher fashioned out of sandpaper. Unable to see the drawings or use the mirror by means of which deaf children learned lip positions, Tad was taught vowel sounds by touching the lip position diagrams Miss Sophie constructed out of pipe cleaners. After four years of work with Tad, Sophia Alcorn turned him over to Inis B. Hall, another teacher at the South Dakota school, whom she had trained in the method she named "Tadoma" after her two pupils.

If deaf children unable to see could learn speech with the help of their fingertips, could such tactile methods help sighted deaf children acquire more natural speech patterns than they could through visual instruction? Intrigued by this question—"I am constantly amazed at how much the fingers can convey to the brain"—Miss Sophie spent the remaining years of her professional career at the Detroit Day School for the Deaf, exploring the use of vibration techniques for teaching language and speech to sighted deaf children. It was Inis Hall who stayed with the education of the deaf-blind; when Tad Chapman was admitted to Perkins in 1931, she was asked to accompany him and to launch the school's deaf-blind department. From that day forward, all Perkins' deaf-blind pupils who were capable of learning it were taught by the vibration method, which Miss Hall modified and amplified as she gained experience in its use with different children. In 1943 she moved to the California School for the Blind to head its newly opened deaf-blind unit, remaining there until her retirement in 1952.

Inis Hall was an instructor at one of the summer graduate courses jointly sponsored by Perkins and the Foundation at Eastern Michigan University in 1949, 1950, and 1951. Although enthusiastically received, these courses, attended mainly by teachers of the deaf, failed to produce a sufficient yield of qualified instructors for doubly handicapped children, whose known numbers were steadily growing. The Foundation's register showed 190 deaf-blind boys and girls under the age of twenty in 1953; six years later the children's list held 350 names.

What was happening with these 350 children? A 1959 report gave some details. About 20 were preschoolers under the age of five, 80 were attending schools which had departments for the deaf-blind, 70 were in institutions for the mentally retarded, and 180—just over half the total—were living at home, not enrolled in any educational program whatever.

Numerically, the situation was not much different in 1962 when M. Robert Barnett delivered a detailed report on the deaf-blind to the AAWB convention. He did, however, add a significant detail. The Foundation was keeping a "watching list" of children who, though not yet classifiable as deaf-blind, were showing progressive losses in hearing, vision or both; there were 50 children known to be moving toward deaf-blindness.

Neither Barnett nor anyone else possessed the power to predict that, by the time AAWB met two years later, the nation would be in the midst of the maternal rubella epidemic that was to add not just 50 but hundreds upon hundreds of deaf-blind children to the national picture.

Disappointed by the negligible results of the summer graduate courses for teachers, in 1952 the Foundation approached the AAIB and its counterpart, the Conference of Executives of American Schools for the Deaf, asking each professional association to appoint a committee to explore the question of how deaf-blind children could be given better opportunities for education. The two associations held a conference in April 1953 at which they joined forces with the Foundation to organize the National Study Committee on Education of Deaf-Blind Children. Although the committee's roster was high-powered, and an amicably cooperative spirit prevailed in its meetings of the next few years, no more constructive results were produced than had been the case more than 20 years earlier, when the first attempt had been made at forming an operating partnership between educators of the deaf and educators of the blind.

There were, however, some useful by-products of the committee's brief existence. The Iowa School for the Deaf, which had a unit for deaf-blind children, initiated a three-year undergraduate teacher training program in 1953; although the program was later discontinued, it did yield a few more teachers. More enduring was the one-year graduate course organized in 1955 by Perkins, originally in affiliation with Boston University and later with Boston College. For more than a decade it was the sole such teacher training program, and it made possible a steady buildup in Perkins' deaf-blind unit, which grew to 79 children in 1972. The Perkins course produced about five new teachers a year, most of whom were employed by the school; there was little surplus for other parts of the country.

An effort to meet that need was made by the Foundation in 1954 when it employed Sophia Alcorn, then newly retired from the Detroit school where she had spent 23 years as principal, to serve as consultant to a western school for the blind then opening a deaf-blind unit. She subsequently visited and screened 64 deaf-blind children uncovered through a new casefinding sweep. When her one-year consultancy ended, the Foundation added two staff members to its deaf-blind department to pursue casefinding and field consultations to local agencies.

Locating deaf-blind children, training teachers to work with them, mobilizing community resources to serve them, were all hurdles; but trickiest of all was evaluating each child's developmental status to determine degree of disability, potential for learning, and the kind of preschool or educational program best calculated to meet his or her needs. A diagnostic facility was required, where individual assessments could be made and individual courses of treatment prescribed.

What may well have been the Foundation's cardinal contribution to the education of deaf-blind children was its decision in 1957 to sponsor such a diagnostic clinic at the Syracuse University Center for the Development of Blind Children.

For the next 12 years the center conducted monthly diagnostic sessions for deaf-blind children. Over this period, 75 children were brought in, each child accompanied by one or both parents and by a social worker from his home community. The costs of the services, travel, and maintenance expenses were defrayed by the Foundation when not available from other sources. Each session lasted four days, in the course of which a team of specialists examined the child, interviewed the parent or parents, and consulted with the accompanying social worker, whose role was to give psychological support and reassurance to parents under considerable emotional strain and then to take responsibility for implementing the evaluation team's recommendations.

The 36 boys and 39 girls were residents of 21 states; they ranged in age from under two to twenty-one, with about half under school age. Following evaluation, most of the children of school age were enrolled in the educational program recommended by the diagnostic team; a small number were deemed in need of institutional care. For the preschoolers, developmental programs in their home communities were prescribed.

To explore the dimensions of such developmental programs, the Syracuse team conducted and the Foundation financed two six-week treatment sessions during the summers of 1961 and 1962, working first with four and then with eight children whose problems were exceptionally severe because of one or more handicaps in addition to deaf-blindness. These sessions were designed to ascertain what was involved, professionally and administratively, in serving such multi-handicapped children. Hindsight shows this pilot effort to have been prescient; the rubella epidemic was yet to come.

A vexing problem which arose repeatedly throughout the Fifties concerned the deaf-blind children who were ready for schooling but whose states neither maintained schools that could serve them nor provided funds to pay for their education in out-of-state schools. Such children could hardly be kept in deep-freeze while the necessary laws and appropriations were enacted; the Foundation met the situation by paying out-of-state tuition fees for a total of 44 of these youngsters, while simultaneously striving to have the deficiencies in state laws remedied.