Chapter 10: The Talking Book

In the ordinary course of events, blind people lag behind their sighted fellows in reaping the benefits of technological progress. There was, however, one shining exception. For fourteen years before their seeing neighbors caught up, blind people were using the long-playing phonograph record popularly known as the LP. They had another name for it. It was called the Talking Book.

Of all the devices that blazed paths of progress for blind people in the twentieth century, the Talking Book was in a class by itself. With a single spin of a turntable, it opened the world of reading to the three out of four blind adults who had never mastered finger-reading well enough, if at all, to use it as a satisfactory means of communication. That the Foundation's development of the Talking Book in 1934 followed so closely on the heels of the braille breakthrough it had itself engineered is, as one observer put it at the time, "a coincidence not without irony." From the start, the Talking Book was destined to overtake braille, speedily and permanently, as the broadest channel of literature and information for blind people of all ages.

The basic idea was not new. When Thomas Edison applied for a patent for his Tin-Foil Phonograph in 1877, one of the ten potential uses he listed for his invention was "phonograph books, which will speak to blind people without effort on their part." Interestingly, this item was second in his list of ten; "reproduction of music" was fourth.

Why, then, did it take more than fifty years before Edison's idea found practical application? It was primarily a matter of technology. Edison's invention used revolving cylinders coated with tinfoil, wax, hard rubber, or similar substances. Just before the turn of the century, the flat platter replaced the cylinder, and shellac became the major ingredient used in molding such platters. For many years thereafter, the standard phonograph record was played on a spring-wound or electrically driven turntable revolving at 78 revolutions per minute. At this speed the two popular record sizes—10 and 12 inches in diameter—had playing times of three and five minutes respectively. These early 78 rpm shellac records reproduced music with reasonable fidelity, but they also had significant drawbacks. They were expensive. They were heavy—the average 12-inch record weighed more than half a pound. They were fragile—a dropped record meant a broken record.

During the Twenties, the advent of radio brought about some radical changes in recording techniques. Programs and commercials recorded in New York studios had to be shipped to radio stations all over the country to be put on the air in accordance with local schedules. The breakable shellac records could not withstand the vicissitudes of postal handling. Moreover, a half-hour program would have required the playing of at least six large platters with irritating gaps in continuity between changes. To overcome these obstacles radio engineers developed what were called electrical transcriptions that could play continuously for 30 minutes. These were 16-inch discs, made out of aluminum or a semi-flexible cellulose acetate compound, and designed to be played on oversized turntables revolving at the slower speed of 33⅓ rpm.

This, the reader will recognize, is how modern long-playing records perform, but it was not until 1948 that both the LP and the instrument to play it were perfected to reproduce music well enough for the commercial market. In the Twenties there were still too many unsolved technical problems. In the Thirties, when some of these problems had been overcome, economic conditions militated against successful promotion of luxury goods, and during most of the Forties wartime shortages of materials and labor had the same effect.

An extra spur to the science of recording during the late Twenties was the newest entertainment miracle—the talking motion picture. To provide the sound tracks for early talkies, major film and recording companies invested lavishly in research and development. It was in the engineering laboratories of these studios that the basic experiments were conducted which, after examination of the many alternate methods and materials capable of reproducing sound, opted in favor of a constant turntable speed of 33⅓ rpm using flexible, relatively unbreakable records manufactured out of acetate mixes.

One person who followed all of these technical developments with keen interest was Robert Irwin. In 1924 he was visited by John W. Dyer, a young man whose father, Frank L. Dyer, had just applied for several patents covering variations on existing recording methods: turntable speeds slower than 78 rpm, grooves narrower than the prevailing standard and spaced more closely together than the customary 90 to 100 lines per inch. The senior Dyer was a mechanical engineer turned lawyer who had been patent attorney, then general counsel, for the Edison companies. At the time of his son's visit to the Foundation he was in independent practice as an engineering consultant.

Irwin was immediately intrigued by the potentials of the Dyer patents. He wrote a friend in April 1924 that there was "a scheme simmering in which I am tremendously interested … for making phonograph records which will contain 15,000 words on a side of a 12-inch disk," which could be manufactured cheaply and played on an inexpensive playback machine. "If we do not die too young, you and I may both live to see some revolutionary changes in books for the blind," he wrote another friend a few months later.

The prospect that records could be used to read books to blind people had strong appeal for Irwin. He once confided: "I have always dreamed of books on phonograph records ever since my first hearing of a squeaky Edison cylinder. I was never a rapid braille reader. … When I was a boy … and had earned a few pennies to spend, I used to save up those pennies to hire a rapid finger reader to read stuff to me that I wanted to hear."

Irwin knew nothing about the phonograph business in 1924, but he acquired a liberal technical and commercial education in succeeding years. Among other things, he eventually learned that the Dyer patents, which were granted in 1927, did not stand up in court. Dyer had counted on having the major record companies buy the rights to his patents; when they refused and went ahead with their own development of slow-speed, close-grooved records, he sued for patent infringement. His suits lost, on the grounds that his patents did not introduce original principles but merely differences in degree of existing processes. Although aware of these lawsuits while they were in progress, the Foundation deemed it prudent to go along with Dyer, inasmuch as he had agreed from the first to forgo royalties or any other financial gain from any use made of his patents on behalf of blind people. By way of non-monetary compensation, however, he asked that his contributions be publicly acknowledged.

In an agreement formalized by an exchange of letters in early 1932, a major stipulation was that all Talking Books produced by the Foundation would acknowledge that the use of royalty-free patents had been given in memory of Dyer's late wife. This pledge was honored even after Dyer's lawsuits lost. Between 1934 and 1948, by which time the patents had expired and Dyer himself was dead, each Talking Book label carried the legend, "Isabelle Archer Dyer Memorial Record."

The other legal hurdle that had to be cleared before the Talking Book could become a reality concerned copyrights. If Talking Books were to command a wide audience among blind readers, they would have to include new and current books as well as literary classics in the public domain. In principle, authors and publishers who had long permitted their copyrighted books to be reproduced in braille were equally well disposed to making their work available to blind readers in this new form, but they raised some understandable objections. "If such discs were used for public halls, or especially for broadcasting purposes, they would fall into the realm of public performance and therefore would be decidedly in competition with books in print," Publishers Weekly for April 21, 1934, pointed out.

How to protect the interests of the copyright owners was the subject of a year-long series of negotiations conducted by the Foundation, first with the Author's League and then with the National Association of Book Publishers. The formula ultimately agreed upon was that a token fee of $25 per book would be paid to protect the copyright principle; that every Talking Book record would be labeled "solely for the use of the blind" and would acknowledge permission of the copyright owner; and that Talking Books would never be sold to sighted people, never be used in public meetings or broadcast on radio. These agreements, originally for a one-year trial period, were subsequently renewed. With minor changes, the same conditions continued to prevail in 1972.

It was no part of the Foundation's original thinking that it could or should itself become a producer of recorded books. With extensive research going forward in the laboratories of the major recording studios, the logical course was to ask for their help in devising a method to make such books available to blind readers at low cost. As early as 1927 approaches were made to both the Western Electric Company and the Edison Laboratories. Charles Edison, son of the inventor, seemed responsive, but his staff saw no commercial possibilities in the idea and the only tangible result was an experimental recording played for the Foundation's board at its meeting three years later.

Another year passed and it became increasingly clear that, in the absence of profit potential, none of the commercial manufacturers had any interest in producing low-cost recorded books. The Foundation made one last try. In February of 1932 Migel went to see David Sarnoff, president of the Radio Corporation of America, with a plan he subsequently confirmed in writing. The Foundation would provide the narrators to record the books and would handle distribution of the finished product if RCA would manufacture the records and sell them at cost.

Sarnoff, like Charles Edison before him, gave the plan his general blessing, but discussions with his manufacturing chiefs quickly revealed that, even on a non-profit basis, the use of a large plant's facilities for the tiny production runs the Foundation had in mind would entail prohibitive costs.

There remained only one option: do-it-yourself. The following month the Foundation made a formal approach to the Carnegie Corporation. Carnegie grants in 1927 and 1928 had been instrumental in effecting major reductions in the cost of braille books, Irwin reminded Dr. Frederick A. Keppel, the Carnegie president. There was now in prospect a new method of publishing books that would yield even more dramatic benefits to blind readers:

I have in my office a record capable of playing 25 minutes on each side, and containing approximately 4500 words [per side]. Every word is perfectly clear and pleasant to the ear; surface sound has been almost entirely eliminated; and what is most gratifying, the cost of production has been reduced to the point where phonograph record books can be produced as cheaply as braille books were a few years ago.

Recorded books, he noted in a follow-up communication, "could be loaned scores—if not hundreds—of times before they were worn out. What is perhaps of most importance—nearly every blind person, after two or three lessons, could learn to operate the phonograph, and thus read to his heart's content."

In requesting an initial grant of $15,000 for experimental work, Irwin admitted candidly that this would be just the beginning. An additional $35,000 to $40,000 would be needed for equipment to begin production. The Foundation had a long-range plan in view; it would launch a campaign to supply blind people with inexpensive phonographs to play Talking Book records and would try to have part of the annual $100,000 federal appropriation for books for the adult blind used for books in recorded form.

Nowhere is the boldness of Robert Irwin's imagination better illustrated than in the unqualified statement he made to Keppel: "I believe that the libraries for the blind of the future will be stocked with phonograph records instead of braille books, and that these records will be loaned through the mails just as braille books are today."

Irwin's daring was all the more remarkable in view of the economic and psychological climate of the time. Nineteen thirty-two was one of the bleakest years of the depression. The Foundation itself was in financial straits. Its operating budget, which had reached $126,000 in 1929, had been cut and cut again. The figure for fiscal 1932 was under $100,000 and would shrink to $87,500 the following year. Not only had contributions fallen off but the yield from invested funds was also reduced. Corporate and municipal bonds were in default, dividends on stocks were cut or omitted, and the real estate holdings and mortgages which had been fruitful investments in the Twenties were not producing their customary income. Fortunately, the investment policy had been thoroughly conservative and in the long run relatively few capital losses were sustained. But stringent measures were required to avoid yearly operating deficits. In 1933 staff members were asked to accept salary cuts of 14 to 18 percent as well as mandatory two- to four-week summer vacations without pay. In some instances they did not even take the vacations, but contributed their unpaid services.

Paradoxically, the very fact of the depression helped the Talking Book become a reality. At precisely the right moment an industrial layoff brought precisely the right man into the Foundation orbit. He was a talented young electrical engineer named Jackson Oscar Kleber, whose experience included employment in the recording laboratories of both the Radio Corporation of America and Electrical Research Products, a subsidiary of the Bell Telephone Laboratories. Kleber was not only up on all of the latest developments in sound-recording technology but, through former colleagues, had access to news of what was going on in all of the major laboratories. With Kleber on staff, Irwin wrote Dr. Keppel in a final follow-up on May 23, 1932, "we start our investigations right where the RCA Victor and Bell Telephone Labs have left off."

At its meeting the next day, the Carnegie Corporation board voted a $10,000 grant. To raise the balance of the required amount, the Foundation applied to John D. Rockefeller, Jr.'s General Education Board, but was turned down. The last arrow in its quiver, however, hit the target. Mrs. William H. Moore was a wealthy and generous woman who in 1930 had contributed $20,000 to the endowment fund. Asked to give the $5,000 that would make up the difference between the Carnegie grant and the $15,000 needed for initial experimentation, Mrs. Moore not only assented but made a similar gift the following year and, when the Foundation was constructing its own building in 1934, gave $15,000 more to meet the cost of equipping the Talking Book studios.

J.O. Kleber got to work at once. A restless, quick-witted individual, he was the prototype of the "basement inventor"—the kind of man who constantly toyed with ideas for mechanical and electrical gadgets and who approached every problem with the delighted anticipation of a child working at a puzzle. "The doggondest collector of odds and ends I ever knew," is the way one colleague described him. "Anything that looked as if it might be useful in some Rube Goldberg experiment would be pried loose from a junk pile and carted off to his house. … things like electric motors, pumps, old amplifiers and speakers, and probably anything else that had wires going to and from it."

Given this type of mind, Kleber was not in the least fazed by the staggering array of technical questions before him. What type of compound would produce records flexible enough to be shipped by mail, durable enough to stand up under circulating library use, thin enough to occupy minimum shelf space? What kind of needle could play such records without damaging them? Could a sturdy record player be developed out of standard parts at a cost low enough for the average blind person to afford? What would be the most economical method of manufacturing Talking Books in editions as small as 100 copies? Which of several methods of recording should be used in making the masters? How close together could the grooves on the records be cut without loss of clarity or durability? (The greater the number of grooves, the greater the amount of text on a platter.) What would be the best reading speed for the narrators whose voices were to be recorded? What vocal qualities would be desirable in such narrators?

Kleber's confidence and enthusiasm were shared by Irwin, who was sufficiently sanguine over the prospects of the Talking Book to make a public announcement of the new project at the 1932 convention of the American Association of Instructors of the Blind, dramatizing his remarks with the playing of test recordings.

By November of that year, when the Foundation applied successfully to the Carnegie Corporation for a second $10,000 grant, it had nearly finished equipping a makeshift studio for production of master recordings, was completing arrangements for the masters to be processed and pressed at relatively low cost, had developed two designs of inexpensive electric playback machines, and was working on a spring-driven model for use in rural homes not equipped with electricity.

Some months earlier, steps had been taken to clear the way for an essential element in the overall strategy: having recorded books made eligible for purchase and distribution by the Library of Congress on the same basis as braille books. The Pratt-Smoot Act of 1931 had authorized annual appropriations simply for "books for the adult blind." When Senator Smoot and Congresswoman Pratt filed an amendment to include books in recorded form, objections were promptly raised by the braille publishing houses. Senator Jesse H. Metcalf of Rhode Island, who headed the Committee on Education and Labor which had jurisdiction over the bill in the upper house, solicited the views of the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam. The Librarian's response was on the cool side:

Since the purpose of the original bill was to increase the literature available to the Blind, an amendment which simply enlarges the form in which such literature may be provided seems in principle consistent.

The particular form just now suggested—a phonograph record—is not yet perfected. Its success depends upon apparatus inexpensive as compared with the existing phonographs, and which may therefore be brought within the means of the blind themselves.

Assuming the records to be produced, the availability of them to any blind person will depend upon his possession of the phonograph itself. Until some assurance of that possession generally (either through purchase by the blind themselves or by free distribution through some fund not yet in sight), the prospect of the employment of such records seems remote.

When the Senator forwarded a copy of this letter to the Foundation with a request for comments, Migel replied that in order to have blind people supplied with talking machines, there would have to be funds for recorded books. He went on to state: "When it has been made perfectly clear that the blind book appropriation may be used for the purchase of phonograph record books, our Foundation proposes to launch a nation-wide movement to interest local communities in supplying their blind citizens with talking machines." Moreover, "there is nothing mandatory in S 5189. It simply authorizes the Librarian of Congress at his discretion to publish books for the blind on phonograph records."

That the braille publishers were not mollified became apparent when the Senate Committee on Labor and Education held a hearing on S 5189. In a letter dated February 23, 1933, Irwin wrote his friend Calvin Glover in Cincinnati:

Dear Cal:

Well, I got on to Washington in time to appear before the Senate Committee and tell them about the Talking Book. When I arrived in town I called up Senator Metcalf's secretary to ask if they needed to have me appear before the Committee. He said he had just received a flock of telegrams from various superintendents [of schools for the blind] protesting against the bill, which would make it possible to divert some of the Pratt-Smoot law to Talking Books. … I called Senator Metcalf's attention to the fact that all of these people were either owners or trustees of braille publishing concerns, whereupon they read the telegrams with much greater interest.

In As I Saw It Irwin added a revealing detail to this sequence of events. When, in the course of the hearing, one senator asked whether anyone would be apt to object to the bill, the chairman, relaying the information Irwin had given, said there had been no opposition except from braille publishers. "Perhaps fortunately," Irwin's book observed slyly, "the members of the committee did not realize that these were non-profit organizations." Needless to say, he did not volunteer to enlighten them.

By holding his tongue during the committee hearing, Irwin may have outflanked the opposition, but he did not underestimate it. The battle two years earlier to secure passage of the original Pratt-Smoot Act had shown him how greatly lawmakers could be influenced by letters from their constituents, and he ended his letter to Glover by asking for a lot of written support.

When, immediately following committee approval, the bill to amend the Pratt-Smoot Act came up on the Senate's unanimous consent calendar, several senators who had received the same telegrams as those sent to the committee asked for deferral. The same thing happened two days later. On March 3, the last day of the 72nd Congress, when the bill was brought up once again, Senator Robert M. LaFollette, Jr. of Wisconsin rose to oppose it. The arguments he raised were that "in the first place there are many persons who are not equipped with proper reproducing machinery to use these records; and in the second place, the funds now provided for the publication of books in braille type are too limited and more money instead of less should be provided [for braille books]."

Objections to the bill, LaFollette said, had come to him, not from a braille publisher but from the superintendent of the Wisconsin school for the blind, "who is absolutely disinterested." That phrase was just as disingenuous as had been Irwin's silence at the committee meeting. The Wisconsin superintendent was J.T. Hooper, who, like all other heads of schools for the blind, was an ex-officio trustee of the American Printing House for the Blind. Furthermore, the superintendent's daughter, Marjorie Hooper, was on the staff of the Printing House.

With Congress slated to adjourn that afternoon, LaFollette then proposed an amendment that would limit to $10,000 the amount to be spent on recorded books out of the $100,000 appropriation available for books for the blind. Senator Frederic C. Walcott of Connecticut pointed out that since the bill had already been passed by the House, any change would force it into conference, for which there was no time left before adjournment. He made a counter-offer. If LaFollette would withdraw the proposed change, "we can declare ourselves here in favor of instructing Doctor Putnam not to exceed in his appropriation for this experiment $10,000 during the first year." The bill was then given a third reading and passed as Public Law 72-439. It was signed by President Herbert Hoover the following morning (March 4, 1933), his last day in office.

The first hurdle had been cleared. A $10,000 limitation on Talking Book expenditures for the 1933–34 fiscal year was not as serious as it sounded. Library of Congress officials had made it clear they would not allocate a single dollar for Talking Books until a sufficient number of playback machines were in the hands of blind readers, and this would take time. Just how many constituted "a sufficient number" was an unanswered question.

There were other questions, too, that demanded immediate answers. What was the best and fastest way to get playback machines into the possession of those who would benefit from them? Only a small number of blind persons would be in a position to buy their own, even at the modest price of $25 or $30. The majority would have to receive Talking Book machines as gifts.

There were three possible ways to finance such gifts. The Foundation could mount a national campaign to raise the money and then distribute the machines to qualified blind individuals, much as it had done with radios. It could forgo a public campaign and turn, instead, to a small number of philanthropic individuals and foundations to underwrite the cost of one or two thousand machines.

The Foundation opted for the third alternative; it would assign field agents to help each state's local agencies for the blind raise funds to supply machines to the people of their own communities. This might be a slower, and perhaps costlier, procedure than either of the others, but it was better statesmanship because it would protect the Foundation from any accusation of taking funds out of local communities for national purposes. Whatever funds the Foundation might be able to raise for its own account could then be used for development and perfection of the Talking Book product, on which much remained to be done.

To spearhead the publicity that would be needed to launch a state-by-state campaign, the obvious choice was Helen Keller. Helen, who was spending the year in Scotland with Anne Sullivan Macy and Polly Thomson, cabled the Foundation in September 1933 to ask whether she would be needed for campaign purposes that winter. Migel wired, then followed up by letter, to say yes. Knowing Helen's determination to reserve her fund-raising efforts for completion of the endowment fund, he wrote that this could be the primary objective but that the Talking Book project was also a possibility.

On receipt of Migel's cable, but before she could receive his letter, Helen cabled back a flat rejection:

if executive committee decides continuing endowment campaign will return at once. talking books a luxury the blind can go without for the present. with ten million people out of work am unwilling to solicit money for phonographs. affectionately keller.

Once Migel's letter reached her, she sent a long, apologetic note saying that a sudden deterioration in her and her companions' health would rule out the possibility of their campaigning for any purpose that winter. "The only thought which sustains me in my upset state of mind," she wrote, "is that under the economic difficulties which continue in America we should not be likely to raise much money this year; and from all reports Dr. Nagle is doing well."

(The Dr. Nagle to whom she referred was J. Stewart Nagle, a former clergyman whom the Foundation employed as a fund-raiser from time to time. It was he who had initially enlisted the support of Mrs. Moore and who persuaded her to make her gifts to the Talking Book program. A man of earnest, jovial personality who was generally well liked. Nagle for some reason irritated Helen and her associates. Anne Sullivan Macy mockingly referred to him as "Jolly Boy," at one point going so far as to exact a promise from Irwin that Nagle would be kept away from the Keller household. It can only be surmised that any successful fund-raiser weakened Anne's oft-stated conviction that Helen Keller alone could attract substantial support for the Foundation.)

Helen's resistance to participation in the Talking Book campaign surprised and dismayed the Foundation trustees. Some attributed her attitude to her own deafness, which might cause her to underestimate the importance of the spoken word. Others thought it to be a reflection of her lifelong Socialist convictions, which understandably put bread ahead of "luxuries." Whatever the reason, she later proved open to persuasion, and although she never went out to raise funds for the Talking Book program, she did make a number of vital contributions to publicizing it.

The opening gun of the Talking Book machine campaign was an article, in the Outlook for October 1933, describing the instrument—referred to as the Talking Book "reproducer"—developed in the Foundation's studio:

This machine is approximately fifteen inches square by eleven inches deep, weighs thirty pounds, and, at present prices of material and labor, can be built in quantities at a cost of approximately thirty dollars each. … The instrument has various controls which make possible a variation in speed, tone and volume of the reproduced sound, thus giving the reader an opportunity to alter the sound to suit his personal requirements. The case may be closed and the entire instrument carried as a suitcase. … [A] spring-driven model can be constructed in quantities at a cost of approximately twenty dollars each.

The accompanying photograph showed an unidentified man (it was Kleber), back to the camera, holding a slim stack of records in front of the opened machine. Propped up on the table for visual comparison were three bulky braille volumes containing the same number of words as the records.

By the following spring, committees organized in 17 states had accepted quotas toward a national goal of 5,000 machines in the hands of blind readers within the next 12 months. Their campaigns looked sufficiently promising for the Foundation's executive committee to authorize the immediate manufacture of 600 Talking Book machines. The Library of Congress, which had decided to begin ordering sound-recorded books once 300 machines had been sold, was now willing to spend the $10,000 set aside in its 1933–34 budget and to commit some funds out of the following fiscal year's appropriation.

What should those first titles be? With the passage of the Pratt-Smoot Act in 1931, Dr. Herman H.B. Meyer, who headed the Legislative Reference Service of the Library of Congress, had been given the additional assignment of directing what was called "Project, Books for the Blind." Dr. Meyer, a scholarly man nearing retirement age, shared the views of Herbert Putnam that books published under Library of Congress auspices should be of "an informing nature" and more or less permanent character, i.e., literary classics. On the other hand, Robert Irwin knew—and scores of letters from blind people confirmed—that overemphasis on the classics could easily kill the fledgling program. The first group of titles, he wrote Meyer, should "include books which the rank and file of seeing people would rush to the library to borrow."

They compromised. As noted in the 1934 annual report of the Librarian of Congress, the Library's first order was for the following titles:

The Four Gospels

The Psalms

Selected Patriotic Documents:

Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the United States

Washington's Farewell Address and Washington's Valley Forge Letter

to the Continental Congress.

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, Lincoln's First and Second Inaugural Addresses.

Collection of Poems

Shakespeare:

As You Like It, Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, Sonnets.

Fiction:

Carroll: As the Earth Turns

Delafield: The Diary of a Provincial Lady

Jarrett: Night Over Fitch's Pond

Kipling: The Brushwood Boy

Masefield: The Bird of Dawning

Wodehouse: Very Good, Jeeves

Even the order in which these titles was listed was a sensitive matter for the Library. Dr. Meyer sent specific instructions on this point: "when you list [the titles] for which the Library of Congress stands sponsor, be sure to print the Gospels and Psalms, the Patriotic Documents, the Collection of Poems, the Shakespeare Plays, first. Where you put the rest doesn't matter."

The initial Library of Congress orders were for 100 sets of each title, distributed according to a circulation formula to the same 24 regional libraries for the blind as those receiving books in raised print. A bill drafted by the Foundation to amend the postal law to extend to Talking Books the same free mailing privileges as braille books was enacted in May 1934.

An immediate dilemma in getting the Talking Book program under way was how to finance the required capital expenditures. Funds had to be laid out for the parts used in manufacturing the hundreds of playback machines for which contingent orders were on hand. Production of the initial batch of records ordered by the Library of Congress meant advancing money for supplies and labor. It was estimated that a revolving fund of $50,000 would be needed to handle these outlays, in addition to $15,000 for continuing research and development. Application was made to the Carnegie Corporation for a $65,000 grant, but this time the cash register rang only faintly, to the tune of $15,000. Appeals to other philanthropic bodies were even less successful. The Foundation, it appeared, would have to borrow from its own endowment fund, with consequent loss of income to its other work. The situation was temporarily alleviated with the providential arrival of a legacy, against which some of the operating funds were borrowed (at the prevailing annual interest rate of 2 percent) until, a year later, an altogether different solution emerged.

Money was not the only headache. The Talking Book program had barely begun rolling when a new controversy was originated by "Fighting Bob" Atkinson of the Braille Institute of America. Although he, along with his fellow braille publishers, had inveighed strongly in 1933 against allowing the Talking Book to come under the Pratt-Smoot Act, he had evidently decided to climb aboard the winning vehicle. Less than three months after passage of the amendment that brought Talking Books within the Pratt-Smoot purview, Atkinson put the Foundation on notice that he had been negotiating "for some time" with a Los Angeles engineer who had patented a "revolutionary" invention for sound recording, called the Readophone. According to Atkinson, the Readophone could outperform the Talking Book in every way: length of recording, price, sound quality, etc. The Foundation responded to this intriguing bit of news by urging Atkinson to bring his machine and some specimen recordings to the AAWB convention, scheduled for later that month in Richmond, Virginia. Atkinson declined, but during the next few months kept up a barrage of publicity to promote the Readophone. It began to look as though a new "war of the dots" was in the offing.

Ever the mediator, Migel urged Atkinson to send the Readophone to New York for examination. If Atkinson or his engineer thought it best to accompany the machine for demonstration purposes, Migel wrote on March 21, 1934, the Foundation would pay half the traveling expense. Atkinson demurred on the grounds that he could not afford the other half. The Foundation then proposed to send its own engineer to Los Angeles, but this suggestion was rejected because, Atkinson wrote, "there are those who are ever eager to copy the work of others and against these we must protect ourselves." His counterproposal was that both he and his engineer would bring the machine to New York, provided the Foundation met all expenses. The Foundation agreed, and May 28, 1934, was set as the demonstration date. There followed a series of almost daily letters from Atkinson, concerned with financial and other details. He estimated his travel cost at $300 and asked for an advance, then revised the figure to $700, and finally announced that he had decided to have his wife accompany him in addition to the engineer. His travel bill, which ultimately came to over $900, was paid by Migel out of his own funds.

Far more irritating than the petty bargaining was the fact that Atkinson repeatedly deferred the demonstration date as he made use of his free trip to arrange stopovers for Readophone demonstrations in Cleveland, Chicago, Boston, and Washington. The delay was serious because—just in case the Readophone should turn out to be everything its sponsor claimed for it—the Foundation had suspended its own Talking Book production.

Inasmuch as the Readophone employed a different recording principle than that used in the Talking Book, an impartial committee of experts was assembled to evaluate the two machines. This unpaid "jury" consisted of six sound-recording engineers: two from the staff of RCA Victor, one employed by the Electrical Research Products affiliate of Bell Laboratories, and three associated with independent recording studios.

The demonstration finally took place on June 12, and immediately thereafter the technical group filed a unanimous report rejecting the Readophone. Their major point was that its "revolutionary" principle—known as the constant linear method of recording—had been in existence for many years and had been tried repeatedly but that no commercial manufacturer, despite heavy investment in engineering research, had succeeded in perfecting it to yield consistently good performance. The report concluded by recommending that the Foundation should continue to "adhere to the system of constant turntable speed as is utilized in commercial machines. …"

Although the Foundation now felt confident about resuming its production of Talking Book machines and recordings, it was not in Atkinson's nature to take a defeat lying down. He went ahead with his scheduled demonstrations and urged the groups of blind people who attended to write the Library of Congress, asking it to sponsor recorded books that could be played on the Readophone. Because of the difference in recording techniques, Talking Books could not be used on Readophone machines, and vice versa.

Even before his trip to New York, Atkinson had notified Library officials of the development of the Readophone and they had given him the same response they had given the Foundation. The Library would not begin to purchase any type of recorded books until at least 300 machines for playing them were in the hands of blind readers. Moving on to Washington after the New York demonstration, Atkinson demonstrated his machine to Dr. Meyer. He also took the precaution of providing himself with an alternative. He wrote Migel that "when I told him [Meyer] that we could easily equip to make talking book records for the machine developed by the Foundation, he said he would give us a chance to bid on such records."

The latter possibility never materialized. Neither did production of the Readophone. The principal effect of the entire affair was arousal of uneasy suspicions in thousands of blind people. It was the Library of Congress that finally put an end to this troublesome situation. When nearly a year had passed and, despite the hullaballoo, only a handful of Readophones had been ordered, Dr. Meyer wrote Atkinson on February 21, 1935, that the Library would not buy any records that could not be played on the Foundation machine. It refused "to be precipitated into a fight between rival reproducing machines for the use of the blind, a fight similar to the struggle over embossed types of several decades ago."

The Readophone affair undoubtedly contributed to thwarting the Foundation's goal of placing 5,000 Talking Book machines in the hands of blind readers within 12 months. Something was needed to move the program back into high gear and the person to supply the motive power was Helen Keller, who had now returned to the United States. Helen was not free to go out campaigning because her teacher was again gravely ill, and she was steadfast in her refusal to raise money for the Talking Book program. But she agreed to use her influence in its behalf. The Foundation had a promise from the Columbia Broadcasting System to devote a network broadcast to promotion of the Talking Book, and in November of 1934 Helen wrote letters to outstanding radio personalities soliciting their participation.

Alexander Woollcott—wit, critic, essayist, storyteller, anthologist, and public personality—had an enormous listenership for his weekly "Town Crier of the Air" broadcasts. Effervescent, impulsive, sentimental, he was an early and ardent advocate of the dog guide movement and had met Helen and her teacher at a fund-raising dinner for the Seeing Eye. He promptly added them to his eclectic circle of friends. When he learned of Anne's hospitalization he sent roses every day to brighten her sickroom; he also dropped in to read to her at every opportunity. It was said that when she died, two years later, the last words she tapped into Helen's hand were, "You must send for Alexander. I want him to read to me."

Helen's letter to Woollcott about the broadcast, written with typical poetic grace and imagery, brought his assent. Also saying yes were Edwin C. Hill, the eminent news commentator, and the noted Irish tenor John McCormack.

Will Rogers went even further. Two days before Christmas he published in his widely syndicated newspaper column most of the letter he had received from "the world's most remarkable woman." Rogers had never met Helen Keller; theirs was a pen-pal friendship which had begun in 1929 when, as part of the endowment fund drive, copies of Helen's book Midstream were sent to numerous celebrities. Rogers had been among the few who did not acknowledge the book or its accompanying note. Helen then wrote an impishly coquettish letter asking him, as "the magician of words," to devote a column to an appeal for public support of the Foundation.

Rogers had responded by sending a check for $500. "Here's my little dab," he wrote, "it's not much on the way to two million but I just don't want Rockefeller to be the only one in the R's." He had promised to write something about the campaign for funds if he could think up a way to approach the subject, but this never materialized. His publication of the letter Helen wrote him four years later may have been his way of making good on that overdue promise.

The network broadcast and other major publicity efforts were a help; so was the growing list of Talking Books which the Library of Congress now began to order. By January of 1935 the number of titles had reached 35, with 20 more promised before the end of the 1934–35 fiscal year. The American Bible Society and the New York Bible Society, which had joined in financing the first recordings of the Gospels and the Psalms, said they would sponsor recordings of the full texts of the Old and New Testaments.

In reporting these developments to the Carnegie Corporation, Robert Irwin also mentioned the need for research to develop an inexpensive method of disc recording which "would render practicable the transcription of Talking Books by volunteer workers somewhat similar to the work carried on by volunteer hand braille transcribers at present." It was to take more than a dozen years before this idea became a reality, but its place in the grand design was clearly visualized when the Talking Book was in its infancy.

Midway through the 1934–35 fiscal year it became apparent that $100,000 a year could not be stretched by the Library of Congress to cover the needs of blind readers in both braille and sound-recorded form. Talking Books had received nearly a third of the year's appropriation. To allocate any more in order to satisfy the clamor from readers for recorded books would be to inflict serious damage on the publishing program for finger-readers, and no one wanted to see that happen. It was time to raise the ceiling on the federal appropriation. An amendment to the Pratt-Smoot Act authorizing an increase to $175,000 was introduced early in 1935 and passed without difficulty in May.

That there was no organized opposition this time around was due to the stipulation in the amendment that the Library of Congress could expend up to $100,000 for braille books and up to $75,000 for literature in recorded form. With their original allocation restored, the braille publishers had no reason to complain, although some thought it would be better if the two appropriations were divorced. A.C. Ellis, who in 1930 had succeeded the late Edgar E. Bramlette as superintendent of the American Printing House for the Blind, was one of these. He sent Irwin several firmly phrased letters urging separation, but eventually yielded to the latter's conviction that the bill would be more acceptable to the Library administrators if they were left free to decide how the appropriation should be allocated. In the course of this correspondence, Irwin ventured the shrewd guess "that you will [some day] wish to push the publication of Talking Books yourself …" and offered him assistance at the proper time. Ellis admitted "there is some probability that the Printing House will some day develop a phonographic book department." He took Irwin up on the offer of assistance and asked for information about costs and other factors entailed in equipping a recording studio. Kleber prepared detailed estimates and subsequently went to Louisville to discuss them with Ellis and his staff.

As to the bill raising the appropriation for books for the blind, one point made in the brief discussion which took place on the floor of the House before unanimous passage was voted is worth noting. In presenting the Library Committee's affirmative recommendation, Congressman Kent Keller observed that "the machines for using these records are not to cost the Government a penny. They are provided for the blind people of the country by liberal-minded people who are interested in them."

This was true enough at the time, but it was due to undergo complete reversal within a matter of months. It was with that reversal that the Talking Book finally came into its own.

There is no clue in the files of the American Foundation for the Blind as to just who conceived the idea of having Talking Book machines manufactured as one of the work relief projects initiated under the New Deal. The first document bearing on this, a letter written to Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 17, 1935, discloses a fully thought-out plan. After explaining the Talking Book and what it meant to blind persons, it stated:

Through private channels our Foundation has been able thus far to place in the hands of the blind thirteen hundred Talking Book machines—sold at actual cost of manufacture. There should be at least ten thousand machines in the hands of the blind, but, unfortunately, the blind as a whole are not people whose means would enable them to procure these machines.

We, therefore, respectfully submit to you the request that either through the Public Works Administration, or through any other means within your power to grant, a sufficient sum be appropriated for the production of, say, five thousand Talking Book machines.

The manufacture and assembling … would give employment to several hundred people directly and indirectly in the production of tubes, motors, cases, radio sets, earphones, etc. So that, in addition to the benefit conferred upon the blind, the employment of a large number of people would be a considerable aid to industrial recovery.

These machines can and should remain the property of the Federal Government, and might be distributed through the Library of Congress or loaned to the various State Commissions for the Blind to be loaned without charge to the blind.

Signed by M.C. Migel, the letter ended with a request that he and Helen Keller be allowed to discuss the proposal with the President. At the conclusion of that meeting a few weeks later, F.D.R. picked up the telephone and instructed Frank C. Walker of the National Emergency Council to expedite the project. He also communicated his personal interest to Harry L. Hopkins, administrator of the Works Progress Administration, and to Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor.

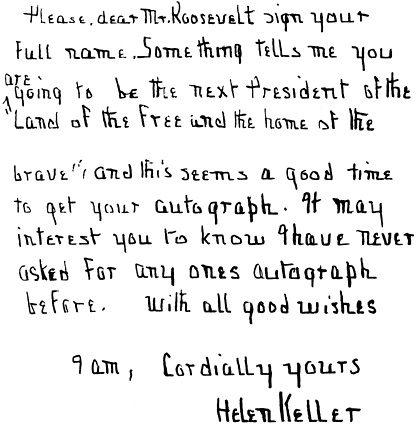

Helen had never been face to face with Franklin D. Roosevelt before this meeting, but they had exchanged letters. Their correspondence had a curious beginning. In 1929 one of Helen's fund-raising letters had gone to Roosevelt, then governor of New York State, inviting him to become a member of the Foundation. He declined, but forgot to sign his note. Impulsively, Helen sent the letter back to Albany with a handwritten message on the back. In her square printed script, she painstakingly lettered:

Roosevelt returned the letter to her, signed, and thus began a relationship of mutual regard which Helen nourished by sending him occasional admiring notes when he made public pronouncements that particularly pleased her. At a political dinner in Washington attended by the President early in 1935, Will Rogers, serving as toastmaster, casually mentioned his forthcoming broadcast on behalf of the Talking Book, whereupon F.D.R. jotted on a card passed to Rogers, "Anything Helen Keller is for, I am for." Rogers quoted this in the course of his broadcast appeal.

Such incidents may have helped pave the way for Roosevelt's sympathetic response to the Foundation's request. Also helpful was the fact that a member of the Foundation board, Mary V. Hun of Albany, New York, was a close family friend and long-time political associate of Roosevelt; during his governorship she served as chairman of the New York State Commission for the Blind. Finally, there was the fact that just a few months earlier, Franklin D. Roosevelt had become honorary president of the American Foundation for the Blind.

It was commonly believed, during the Roosevelt era, that a strong element in his generous attitude toward work for the handicapped was the fellow feeling that grew out of his own physical disability. Whatever the reason or reasons, F.D.R.'s personal endorsement of the plan to have Talking Book machines manufactured as a work relief project was probably the only thing that saved it from strangulation by red tape.

Technically, the plan did not actually qualify as a work relief project. The Works Progress Administration had been established to give jobs to the unemployed, and its administrative policy stipulated that 75 cents out of every dollar should be spent for direct labor. The manufacture of Talking Book machines, however, was primarily an assembly job using commercially available turntables, motors, speakers, amplifiers, etc. These were purchased from a dozen different sources; the labor component, which involved assembling and fastening, represented less than 40 percent of the total cost of the finished product.

Threading through the bureaucratic layers to gain permission for this deviation from the WPA formula was no easy task. Another challenge was obtaining the agreement of the Library of Congress to take title to the Talking Book machines once they were manufactured. The Library was not keen on the idea; involvement with ownership and distribution for record players was an unprecedented, seemingly alien, function for a scholarly institution. The Foundation offered to do everything in its power to ease things.

"If you wish us to do so," Migel wrote in a letter to Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam,

the Foundation will arrange with the State Commissions for the Blind in each State to be responsible for the machines allotted to that State—the different Commissions to determine which blind people may receive machines on an indefinite loan under such conditions as you may wish to prescribe. If you desire, the Foundation will undertake to arrange for the Commission or any other agency in each state to check up on the machines periodically and to give instruction in their use. In short, the Foundation will relieve the Library of Congress so far as you may desire of all details connected with the distribution of these machines. …

It was on this basis that the Library was persuaded to "sponsor the orphan child," as Irwin put it in a chatty letter to Helen Keller at the end of August. Supervising the manufacture of 5,000 machines at a cost of $210,000 would be "a nice messy job." Still: "What a job it would be to raise this money from private sources!"

On September 19, 1935, President Roosevelt signed the executive order to the Treasury transferring $211,500 to the Library of Congress for the construction of Talking Book machines. The Library then appointed the American Foundation for the Blind as its agent to supervise the project; Robert Irwin was sworn in as a dollar-a-year Assistant of the Library of Congress for this purpose.

By December a loft had been rented at 475 Tenth Avenue in Manhattan and some of the men who had been assembling Talking Book machines in the basement of the Foundation building moved over to set up production lines in the new premises. Project NEC No. 11,620 was on its way.

WPA projects as a whole were the subject of innumerable jokes in those days; the satiric term "boondoggling" came into the language to describe the activities of little or no practical value to which some WPA workers were assigned. The Talking Book machine project, however, was one of the glorious exceptions. Although its white-collar workers were totally inexperienced in assembly operations, the enthusiasm and skill of the supervisory crew brought them rapidly into line. Among both workers and supervisors (the latter earned $20 for a 40-hour week, the former $16.40) were several unknowingly beginning lifetime careers in work for the blind. Arthur Helms, who became production manager of the Foundation's Talking Book Division, began in the WPA shop. So did Charles G. Ritter, who later sparked the growth of the Foundation's aids and appliances service.

In charge of the shop as project manager was "the other Kleber"—Chester C. Kleber, known as "C.C." to distinguish him from his cousin, "J.O." J.O. continued at the Foundation, concentrating on design research and supervising production of Talking Book records. C.C. was no inventor; he was an administrator and sales executive, whose skills fitted him admirably both for the managership of the WPA project and for the post he ultimately occupied as general manager of the National Industries for the Blind.

Despite its numerous problems (the inexperience of the workers, a constant turnover as men gradually found their way back to white-collar employment, supplies arriving late or in unacceptable condition, repeated bureaucratic interference from overlapping government units charged with control of WPA expenditures), the Talking Book project went so well that it was renewed time and again over a seven-year period. By the time it was finally discontinued in 1942, it had produced 23,000 Talking Book machines at an overall expenditure of $1,181,000. The contract renewals were by no means automatic; there were several cliffhanging episodes when the threat of imminent termination was averted only by direct appeal to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Increasingly, however, the project made additional friends in influential quarters. New York Congressman Matthew J. Merritt, who inspected the project six months after it opened, was so impressed that he inserted an account of his observations in the Congressional Record:

My first impressions … were those of simplicity, energy, and good management. There are 300 men working on one large floor, which is divided into the necessary sections to cover all phases of manufacture, from preliminary inspection of parts to shipping. It is impossible to doubt that every one of these men derives his inspiration from the sign which hangs at one end of the room. It reads "Every man working here is doing his part to make the blind of the country happier." There is adequate evidence of this in the cheerfulness and energy which these W.P.A. men apply to their work.

Quite early in the game, a logical question arose. If the assembly process could be sufficiently streamlined to fit the fumbling fingers of former clerks, could it not be adapted for blind workers as well? A few unemployed blind men were tried experimentally, aided by special jigs and guides devised for their use in the various operations. This proved so successful that additional blind and disabled people were hired; at one point, when there were 197 WPA men working in the factory, 89 were visually handicapped and 33 others were either deaf or had cardiac limitations.

Blind people everywhere were ecstatic over the WPA-manufactured machines. As for the state and local agencies for the blind handling distribution, their reactions reflected both gratification and distress. Typical was this letter from a home teacher of the blind in Jefferson City, Missouri:

I have 16 counties with over 800 blind people and 13 WPA Talking Book machines to use in the territory. … I am certain I could use four or five times as many machines as I can get, so what shall I do? My plan is to loan a machine for two or three months to a person, then pick it up and let someone else use it for a while.

This teacher ended her letter with an urgent plea for spring-driven machines as well as the electrified ones. So many similar requests were received from rural districts that provision was made for the WPA project to produce several thousand players that could be hand-cranked.

Throughout the life of the WPA project, and for some years thereafter, the Foundation continued to produce its own Talking Book machines for sale to people who wanted permanent possession of their instruments and were unwilling to wait for one on loan from the Library of Congress. There were various improvements introduced as the years went on. All told, about 5,000 such machines were produced and sold from 1934, when the first ones were put on the market, until 1951, when the Foundation stopped production.

By the beginning of 1937, when 10,000 WPA machines had already been distributed and 5,000 more were in process of manufacture, it was obvious that the 1935 appropriation ceiling of $75,000 for recorded books was wholly inadequate to serve a readership whose number had increased tenfold in two years and was slated to go on growing. A new amendment to the Pratt-Smoot Act was therefore introduced, raising the Talking Book ceiling to $175,000. It passed Congress without difficulty and was signed into law on April 23, 1937. Three years later, by which time the number of Talking Book machines in circulation was up to 20,000, the authorized figure was raised to $250,000. It was next increased in 1942, when the WPA project had ended and for the first time the Library of Congress had to use some of its own appropriation for repair and replacement of the older machines. A further increase in 1944 permitted the expenditure of up to $400,000 for both records and machines. The amount allowed for the machines was relatively small because both labor and parts were in short supply during the war years. Not until the war ended could a substantial sum be spent for new machines. The Talking Book appropriation for the following fiscal year was accordingly more than doubled ($925,000). In this same year, 1946, the ceiling for brailled literature for adults, which had remained constant at $100,000 since 1935, was also doubled.

These levels of expenditure were maintained for a decade. In 1957, when the call for additional funds was sounded once again, Congress decided not to go on patchworking the Pratt-Smoot Act with an endless series of amendments but to lift the legislative ceiling altogether and require the Library of Congress to apply for each year's appropriation on the basis of justified need. Since then appropriations have moved steadily upward. The million-dollar figure, which appeared gargantuan in 1947, was only one-ninth of the sum approved for 1972–73.

Not all the changes dealing with books for the blind concerned rising budgets. There were four which affected the basic nature of the program. The first went into effect in 1939. A phrase was inserted into the law specifying that in the purchase of Talking Books the Librarian of Congress "shall give preference to non-profit-making institutions or agencies whose activities are primarily concerned with the blind." This was to protect the program from lowering of standards through commercialization. A second change, enacted in 1952, removed the word "adult" from the law. A third, ten years later, broadened the program to include musical scores and instructional texts on music in braille and sound-recorded form. This enabled the Library of Congress, by consolidating the holdings of various regional libraries and acquiring additional materials from all parts of the world, to create its national circulating and reference collection for blind musicians and students.

It was the fourth fundamental change, which took place in 1966, that was largely responsible for the quantum jump in Talking Book production, circulation, and expenditures. Public Law 89-522 expanded the eligibility for Talking Book service to all physically handicapped individuals unable to read or handle normal printed material. Readers of Talking Books could now include not only persons suffering from physical limitations caused by such diseases as multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, diplegia, Parkinsonism, etc., but also thousands of visually handicapped adults and children who had not previously been eligible because they did not qualify under the legal definition of blindness.

Although blind children were not eligible until 1952 for Talking Books produced under Library of Congress auspices, they began to benefit from recorded reading in 1936, when the American Printing House for the Blind obtained a ruling that permitted expansion of its schoolbook program for blind children on the same grounds that the 1933 Pratt-Smoot amendment expanded book publishing for blind adults: books were books, whether in raised print or recorded form. The Printing House built a complete recording studio and pressing plant and began, the following year, to manufacture, for distribution to schools under their quota allotments, such Talking Books as Silas Marner, Treasure Island, and Gulliver's Travels. At the same time it obtained a substantial increase in its annual federal appropriation.

Once the Printing House was equipped to produce recorded books for its school constituency, it was in a position to ask for a share of the Library of Congress' orders for recorded books for blind adults. As a matter of sound public policy, the Library welcomed the availability of an additional supplier. So did the Foundation. Having arranged for thousands of new playback machines to reach blind readers through the WPA project, and having secured legislation to more than double the appropriation for Talking Books, the Foundation was unable to produce enough records to meet the stepped-up demands.

Nor did it wish to. Robert Irwin had been sincere when he wrote that there was no desire for a monopoly on Talking Books. The Foundation saw its role as one of continuing research and innovation in all areas which affected blind people. To become primarily a recording studio would be to diverge from its main path. Besides, there were serious financial considerations to be taken into account. Even with part of the Talking Book production diverted to the Printing House, there was an immediate need to invest more capital in plant and facilities. Up to this point, manufacture of Talking Books had been a two-part operation, with the master recordings made in the Foundation studio and the remaining steps—electroplating of the masters and pressing of the finished platters—contracted out to the RCA-Victor plant in Camden, New Jersey. With the prospect that in 1937–38 the Foundation would be called upon to execute more than $100,000 worth of orders for the Library of Congress, prudent management called for investing in additional studio equipment and setting up a small plating and pressing unit. This, Irwin argued in persuading the Foundation board to agree to the new capital expenditures, "would make us more independent of the Victor Company, should they suddenly cease to be as friendly as they are now."

It was a foresighted move. Within a few years, the Victor Company, while friendly as ever, was too busy with high-priority war work to pay much attention to Talking Books. By then the Foundation had learned enough about record manufacturing to be able to handle every step of the process. Initially, this was on a limited scale; only after the war was there sufficient space and equipment to accommodate manufacture of the entire volume of Talking Book orders. In 1950, when a four-story wing had been added to the Foundation's premises, all subcontracting of record pressing came to an end.

The circumstances of the Printing House were different. Located on spacious, state-granted land on the outskirts of Louisville, the Printing House was equipped for all phases of production almost from the beginning. Once it was geared to full-scale operation, it became a full partner in the production of Talking Books. The Library of Congress adopted a conscious policy of dividing its business fifty-fifty between the Foundation and the Printing House, each of which repeatedly enlarged plant and facilities to accommodate the steadily rising volume.

Almost as soon as the Talking Book became a reality, Edward Van Cleve of the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind ordered a few sets of Talking Books to try out in the school's upper classes. The selections were mostly short stories or classic poetry of the kind familiar to generations of high school English students: Byron's The Prisoner of Chillon, Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, etc. In mid-1936 a teacher in Van Cleve's school reported on the ways in which he made use of such recordings and concluded that the Talking Book was "an ally rather than a rival to braille."

This was a point that worried some educators. If blind children learned to depend on recorded books, what motivation would they have to master the difficult and tedious process of finger-reading? The question was valid enough to warrant a serious study that would examine the respective roles of braille and recorded books in the education of blind children. To finance such a study, the Foundation turned once again to the Carnegie Corporation, which responded with a $10,000 grant in late 1938. A few months later, the Foundation was once again fortunate enough to find the right man at the right time.

Berthold Lowenfeld, who had been head teacher at one of Europe's most eminent schools for the blind, the Blindeninstitut in Vienna, had just arrived in the United States as a refugee from Nazi-occupied Austria. A Ph.D. in psychology from the University of Vienna, Lowenfeld not only knew English but had spent the year 1930–31 in the United States as a Rockefeller research fellow studying teaching methods in American schools for the blind. With his long years of teaching experience, scholarly background, and intimate knowledge of blind children abetted by an exceptional degree of personal charm, Lowenfeld was ideally equipped to work with the school superintendents in exploring the educational role of recorded books. Under his direction the Talking Book Education Project, which lasted from 1939 to 1945, enlisted the cooperation of 14 leading schools for the blind in testing the ways in which the child's fingers and ears could work together to enrich his knowledge of the world he could not see.

The project approached its goals in several stages. The first step was to survey the literary classics already available in Talking Book form and select those which could fit into educational curricula at various grade levels. "Learning by Listening," an annotated catalog of such recordings, was distributed to schools and classes for the blind. To facilitate immediate use of the records, Foundation engineers designed a heavy-duty model of the Talking Book machine for production by the WPA project; more than 500 of these were distributed to schools and classes for blind children.

To test the relative educational values of braille and Talking Books, a number of special recordings were made. These presented standard reading material for third and fourth grade children in three different recorded forms: straight reading, reading with dramatization, reading illustrated with sound effects. A comparable selection of stories was presented in braille. Responses by children and teachers in the schools cooperating in the tests were unequivocal: material that seemed dry and uninteresting in braille captured the children's attention when presented in recorded form with sound effects and dramatizations.

To demonstrate the techniques by which imaginatively recorded books could be incorporated into the educational curriculum, a number of study units were put into recorded form. Social studies were enlivened by dramatizations of crucial events: Across the Isthmus (the story of the Panama Canal), Wires Round the World (the story of the telegraph), Haste Post Haste (the story of the postal service). Nature study recordings reproduced bird calls to illustrate a verbal text describing different species of birds, their habits and habitats.

Another objective of the education project was to demonstrate the Talking Book as an enrichment factor in the teaching process. "The speed of the average braille reader is comparatively slow, and this factor necessarily limits the quantity of reading material which may be absorbed by the blind child," Lowenfeld pointed out. The blind child could come closer to parity with the sighted child if, instead of tracing a story with his fingers at 60 words per minute, he could hear it read aloud at the standard Talking Book reading speed of 160 to 180 words per minute.

Practically no children's books other than texts existed in recorded form when the education project began. After examining the range of children's literature and consulting with library experts, Lowenfeld drew up a list of books which the American Printing House for the Blind was then persuaded to produce for distribution through the schools. In the course of the project, 115 such titles were issued in "illustrated" form with dramatized segments and sound effects inserted into the narration.

Once the basic principles had been established, the Talking Book Education Project gained the support of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to extend its special techniques to additional study units. In music, for example, seven junior biographies of great composers were recorded. In place of the piano scores used in the inkprint editions of these books to illustrate the composers' work, the Talking Book editions played recorded excerpts from the compositions. Further enrichment was provided by "musical end papers"—beginning and ending each Talking Book in this series with selections characteristic of the composer's work. Thus the biography of Josef Haydn opened with a section of the Toy Symphony and closed with the final chorus of The Creation.

A report to the Kellogg Foundation describing this and similarly imaginative approaches to the educational needs of blind children also cited the results of tests conducted to identify the respective roles of finger-reading and ear-reading: "comprehension of narrative material is as good by listening to the Talking Book as it is by reading braille … but material which is mainly informative—as in textbooks of physics or chemistry—is better comprehended if read in braille." The comprehension test for narrative material had consisted of an elaborate experiment, in which a 700-page American history book was simultaneously published in braille and in Talking Book form (the former needed 10 volumes, the latter, 54 double-faced discs). So persuasive were the results that a permanent place was assured for recorded books in the education of blind children.

Lowenfeld, who was named director of educational research soon after he joined the Foundation staff, remained until 1949, when he resigned to become superintendent of the California School for the Blind. Although retired from this post since 1964, he continues to exert an active influence in the field of education as consultant, author and editor. Both his professional standing and his personal popularity were publicly recognized when he was honored by the Shotwell Award of the American Association of Workers for the Blind in 1965 and, three years later, by the Foundation's own Migel Medal.