Funding for this product evaluation was provided by the Teubert Foundation, Huntington, West Virginia.

Our two previous evaluations of cellular telephones, in the May 2003 and July 2003 issues of AccessWorld, exposed serious problems in accessibility among four top-of-the line models. In this and the January 2004 issues, we present two evaluations of two other top cell phones, as well as software that, when installed, provides speech output of screen information. In this article, we evaluate the Nokia 3650 cell phone, combined with the Mobile Accessibility software produced by the European company Code Factory. In the January 2004 issue, we will evaluate the TALKS software from the German company Brand & Gröber Communications, which is loaded onto the Nokia 9290 Communicator, a combination phone and personal digital assistant with a compact QWERTY keyboard. In the January article, we will also compare these two telephone-software combinations—the one discussed here and the one discussed in the January issue. These are the only software products available that speak in English.

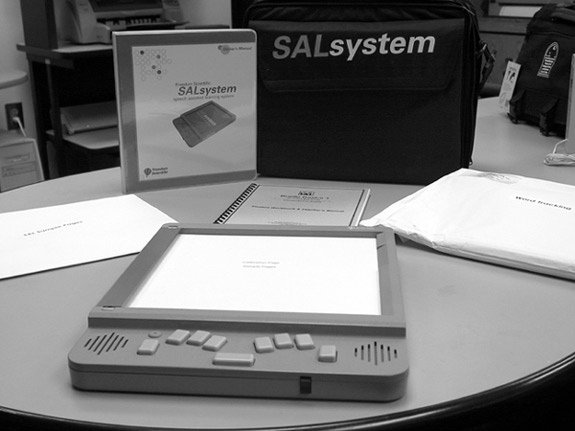

The Nokia 3650

Priced at $299, the Nokia 3650 is relatively large by today's standards, measuring 5.1 inches by 2.24 inches by 1 inch and weighing 4.6 ounces. Its large size accommodates an oversized 2-inch by 1.5-inch display, and the phone features many of today's new innovations, such as web surfing, text and multimedia messaging, a digital camera, and even a video recorder with MP4 playback. Menus are navigated with a circular five-way scroll button, and the phone also has its dialing numbers arranged in a circle similar to the old rotary telephones. The phone features the Symbian operating system and 3.4 metabytes of onboard memory, which gives it the capability of downloading and installing software, such as video games and the Mobile Accessibility software.

Caption: The Nokia 3650 has a circular dial.

Mobile Accessibility Software

Priced at $229 and found at <www.mobileaccessibility.com>, Mobile Accessibility creates a user interface that can assist a person who is blind or has low vision in accessing the features of the phone via keystrokes and synthetic speech output. This software application must be loaded onto the telephone, however, the download and installation process is not accessible.

The Sweet 16

As we reported in our previous cell phone evaluations, before we began our reviews, we surveyed 20 cell phone users who are blind or have low vision to determine which features they would most like to have made accessible. The 16 features that were rated the highest by the respondents became the basis for our evaluation. We looked at whether users would be able to access these features and noted the barriers to accessing them. The evaluation methods we used included

- measuring the ability to identify and use the keypad tactilely

- determining the ability to navigate menus

- noting auditory and vibratory feedback, and

- assessing the readability of the visual display

The following analysis lists the 16 cell-phone features that the respondents rated as the most important for accessibility, and how the Nokia 3650/Mobile Accessibility combination measured up on each feature.

****

****

View a narrative for Box 1.

Keys That Are Easily Identifiable by Touch

Most of the keys on this phone are easily identifiable by touch. However, two keys that are located near the display are flush with the panel and are difficult to find. (Those are two "soft" keys, whose actions change, depending on the text that appears on the screen.) The circular arrangement of the dialing numbers can be difficult to use. Having to count around the circle to find the numbers you want to press can be inefficient and time-consuming. The standard 3-by-4 grid is much more user-friendly for people who are blind or have low vision. In addition, the nib on the 5 key is placed on the top left corner instead of on the middle of the key.

Voice Output

The Mobile Accessibility software creates an interface with voice output to provide access to menus and other screen information, but it does not give a user who is blind access to all the menus or features of the 3650 phone, such as web surfing or voice dialing and speed dialing. Mobile Accessibility must be turned off, and sighted assistance is needed to use these and other features, which must be accessed through the main 3650 interface and menu system.

The voice quality is acceptable, but it is not as clear as that found in today's speech synthesizers, and users may experience frustrating delays in the voice feedback at times. A more serious problem is that Mobile Accessibility often does not come on when the phone's power is switched on, and sighted assistance is needed to activate the software manually.

Accessible Documentation

There is no accessible documentation for the Nokia 3650 phone. The inaccessible alternatives are the print manual and a PDF manual on the Nokia web site <www.Nokia.com>. The Mobile Accessibility software did come with a manual in Microsoft Word format, and it can be downloaded from the Mobile Accessibility web site. However, the manual has many problems. It is not complete, so you need to learn most of the information by trial and error. Also, there are many mistakes in the manual. Furthermore, the manual did not include a description of the buttons on the 3650; instead, it had a picture of the phone with arrows pointing to the various buttons, which is useless for a person who is blind.

Battery Level Indicator

The Nokia 3650 has a battery level indicator on its main screen with six sticks that disappear as the battery level decreases. With Mobile Accessibility active, when you press the pound key briefly, you hear the voice say, "Battery level," followed by "high," "medium," or "low." The 3650 also gives a unique tone every hour for the final three hours of use before the battery finally dies, to alert you that it is time to recharge.

Roaming Indicator

The Nokia 3650 has a visual roaming indicator, but Mobile Accessibility has no audio equivalent.

Message Indicator

Although Mobile Accessibility does not automatically indicate messages, this information can be accessed through the main Nokia 3650 operating system. It has a visual icon to indicate that a voice mail, text, or multimedia message has been received, and it will emit a short tone, along with a vibration, to indicate that a text or multimedia message has been received or that a message came in while you were on another call or while the phone was turned off. You can also use Mobile Accessibility's menu system to navigate to your text and multimedia mailboxes to check for messages. Creating and reading text and multimedia messages are also accessible with Mobile Accessibility.

Phone Book

The phone book, called "Contacts" on this phone, is accessed visually through the Nokia 3650's menu system and can be accessed with Mobile Accessibility. You can assign a shortcut or navigate through the menu system to the Contacts menu and perform most of the contact-management tasks that are available through the 3650 operating system. You can read your contact list; add, delete, or edit contacts; call contacts; and assign unique ring tones to your contacts. You can also record your own ring sounds and assign them to contacts, but you must assign speed-dialing and voice-activated dialing shortcuts for your contacts visually with the regular 3650 menus.

Entering textual contact information, such as a person's name, is done with the alpha-numeric dialing keys, using the letters that accompany the number on each key. For example, you would press the 2 key once for "A," twice for "B," and three times for "C, and you would press the 3 key once for "D," twice for "E," and three times for "F." Other letters are entered in a similar fashion. However, this procedure is not explained in the manual, and the speech echo of the letters entered is sometimes incorrect. For example, when you press the 4 key twice to enter the letter H, Contacts says "G," even though it correctly enters the letter "H" into the edit field.

Phone Lock Mode

The Nokia 3650 has a way to lock the phone with password protection to prevent unauthorized use, but it must be done visually and cannot be accessed via Mobile Accessibility.

Keypad Lock Mode

Both operating systems provide a way to lock the keypad to prevent unintentional dialing while the phone is in a pocket, purse, or briefcase. Mobile Accessibility calls it "Phone Lock," instead of keypad lock, and this option is on the main menu. To unlock the keypad, you simply press two menu keys, so it is not password protected like a true phone lock.

Power Indicator

There is no specific power indicator on this phone. If you have sufficient vision, you can tell whether the phone is on simply by looking to see if the display is on. If you do not have sufficient vision, you can press any number key and listen for a tone, which indicates that the phone is on.

Ringing or Vibrating Mode Indicator

Both operating systems can access what are called "Profiles," which control whether you are to be alerted to an incoming call by tones, beeps, or vibrations. With the General Profile active, the phone will ring; with Meeting active, it will beep and vibrate; with Silent active, it will just vibrate; and with Outdoors active, it will ring louder. The Nokia 3650 has an on-screen icon to indicate which profile is active, but with Mobile Accessibility, you have to navigate to the Profiles menu and choose a profile to know for sure which one is active.

GPS Feature

Some of today's cell phones have a GPS feature that uses global positioning satellites to help emergency services locate you if you make a 911 call, but the Nokia 3650 does not include that feature.

Signal Strength Indicator

The Nokia 3650 has an on-screen icon to indicate the strength of the signal, and Mobile Accessibility can present your signal strength orally. Pressing and holding the pound key for one second will cause Mobile Accessibility to tell you if your coverage is high, medium, low, or unknown or if you have no coverage at all.

Ringer Volume Control

Both operating systems control the volume of the system using their respective menu systems. The volume menu is accessed via Mobile Accessibility's main menu. You can set the volume to low, medium, or high. You can also customize the volume to a level in between these three levels if you like. However, you may want to purchase an optional headset to use Mobile Accessibility in noisy situations.

Caller Identification

When an incoming call is being received, either the caller's number or name is displayed on screen, depending on whether the caller is in your contacts list. Mobile Accessibility will also speak that information if you press the menu key.

Speed Dialing

All tasks involving speed dialing and voice-activated dialing must be done through the 3650 interface and are not accessible via Mobile Accessibility. However, if sighted assistance is used to help program voice and speed-dialing numbers, these numbers can be used with some memorization of the minor keystrokes.

Low Vision Accessibility

The Nokia 3650 has a large 1.5-inch by 2-inch multicolor display with 4,096 colors, but the text on the screen is small, ranging from 10 to 14 points, which is too small for many people with low vision. However, you can use the contrast feature that is accessed through both operating systems to adjust the contrast from normal to high. The keys on this phone are small and have text or icon labels that are too small for most people with low vision to read, but you can use Mobile Accessibility to learn the keys and their functions.

Other Mobile Accessibility Features

Some phone features that are accessible via Mobile Accessibility did not make our Sweet 16 list, but do deserve mention. By pressing and holding the star key for one second, you will hear the time spoken, but it is spoken in 24-hour European time instead of 12-hour U.S. time, and there is a 5-second delay before you hear the time. You will hear the date spoken by pressing and holding the 0 key for one second, but there is a 10-second delay before you hear the date. The Mobile Accessibility menu also features an accessible way to set the time and date and the phone's alarm feature. You can also use Mobile Accessibility to create shortcuts for the various menu items. For example, you can assign the 2 key as the key to access the volume feature instead of having to scroll through the menu system to find it.

There is an item in Mobile Accessibility called Tools, but when you scroll through the menus to open this feature up, there is nothing there. The Mobile Accessibility manual, which actually calls this item Utilities, says to go to the Mobile Accessibility web page to download other applications and functions that can be accessed through this menu item. However, no such applications or functions exist on the Web page.

The Bottom Line

People who are blind or have low vison have been waiting a long time for a cell phone that is truly accessible, but this phone-and-software combination is just one small step toward ending our wait. Although the speaking interface that Mobile Accessibility provides access to has more features than other such devices have, it still does not let you access all the features of the phone that a sighted person can access. The speech synthesis could use some improvement in accuracy, and it is often too slow in responding to commands. The manufacturer of Mobile Accessibility reported that speech synthesis will be available for several more phones in the near future, which we hope will have keypads that are more user-friendly than the rotary-style keys on the 3650. We also hope to see improvements in the future versions of Mobile Accessibility that will provide access to all the phone's features, instead of just to the limited features it now supports. As it now stands, people who are blind or have low vision have to pay more than $500 for this phone-software combination, which gives them access only to the features that a sighted person can access in most of the cell phones that are offered free of charge as part of a service contract.

One thing that this combination does show is that it is possible for a manufacturer to make the features of a cell phone accessible to people who are blind or have low vision. We hope that with more and more phones being offered with operating systems and large memory capacities, we will see some exciting new innovations in the near future.

Manufacturer's Comments

Code Factory

"A new version of Mobile Accessibility, scheduled for release in October 2003, includes a roaming indicator, shortcuts for speed dialing, and a new synthesizer that is more responsive and has a higher speech quality. Future tools will include a calendar, an agenda, calculator, e-mail client, MP3 player, screen magnifier, editor, sound recorder, and a camera program.

"Many blind people have installed Mobile Accessibility themselves. The Bluetooth or infrared port can be activated with a shortcut, and the program can be installed with PC Suite. The program needs to be activated manually only when the phone is plugged in. A sighted person can then tell you once how to activate the software again, and you will know how to do it."

****

View the Product Features as a graphic

View the Product Features as text

Product Information

Product: Nokia 3650

Manufacturer: Nokia Americas, 6000 Connection Drive, Irving, TX 75039; phone: 972-894-4573; Sales: 888-256-2098; web site: <www.nokia.com>. Price: $299, Service available from AT&T Wireless, T-Mobile, and others. Check with your local service provider.

Product: Mobile Accessibility

Manufacturer: Code Factory, S.L. Rambla d'Egara, 148, 2–2, 08221 Terrassa (Barcelona), Spain; phone: 0049-171-3797470; e-mail: <sales@mobileaccessiblity.com>; web site: <www.codfact.com/english>. U.S. distributor: Speech and Braille Unlimited LLC, 3708 East 34th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55406; phone: 877-549-3687; e-mail: <info(speechbraille.com>; web site: <www.speechbraille.com>. Price: $229.